We’ve seen lots of great new films come on the market in the last few years, but there are also a lot of classic films we love—survivors from the pre-digital days that have changed little or not at all since film’s heyday. Here are eight classic films we think every analog photographer ought to try.

Kodak Tri-X 400

Kodak

Say “classic film” and many experienced film photographers will instantly think of Kodak’s B&W Tri-X. Introduced in roll-film form in 1954, Tri-X’s 400-ASA speed made it the film of choice for both photojournalists and amateur photographers, and it remains popular well into the digital photography age. Tri-X is the film that documented the second half of the 20th century in America, and its grainy, contrasty look has become synonymous with monochrome photos of that era.

Tri-X’s popularity came from its flexibility: It was (and still is) well suited to a variety of lighting conditions, and performs nicely when pushed to 800 or 1600 for low-light conditions. Tri-X has been reformulated and refined repeatedly over its 80-plus-year-life, and the latest version, called 400TX, still delivers that same distinctive, stark look. Tri-X has its quirks and it’s not a film that every analog photographer will love, but we think everyone should at least give Tri-X a try.

Available formats: 35mm, 120, sheet, disposable camera

Ilford HP5 Plus

Ilford

Back in the film-only era, Ilford’s Hypersensitive Panchromatic film was—to American photographers, at least—unfairly characterized as a lesser-known alternative to Tri-X. Like Tri-X, it’s an extraordinarily flexible 400 ASA traditional-grain film that is exceptionally easy to work with. It actually predates Tri-X, having been first developed in the 1930s. But while Kodak continued refining Tri-X well into the 21st century, the current version of HP—HP5 Plus—has been unchanged since 1989, making it a true film-era veteran.

HP5 Plus contrasts (heh) sharply with Tri-X in its tonality: While Tri-X delivers harder blacks and whites, HP5 renders the world in more subtle shades of gray, and yet its visible grain gives it an unmistakably classic look. Pushed two stops, it delivers excellent low-light performance with grit and contrast. HP5 Plus is a classic, to be sure, but it’s also a great modern-day tool, as close to a do-everything B&W film as you’re going to find.

Available formats: 35mm, 120, sheet, disposable camera

Ilford FP4 Plus

Ilford

HP5’s low-speed companion is Ilford’s Fine Grain Panchromatic film, and with the demise of Kodak Plus-X it’s now the premiere traditional-grain B&W medium-speed (125 ASA) film on the market. Until tabular-grain film was developed, FP’s image quality was as good as it got: Sharp contrasts, vivid tonality, with a traditional look that celebrates grain rather than trying to hide it.

Like HP, FP has a long history: It was first developed in the 1930s and refined to its current version, FP4 Plus, in 1990. Some photographers regard it as the best B&W film ever made, not just for its look but for its latitude and flexibility: Shot at box speed and developed per the chart, it gives great results, but it also has extraordinary latitude, and you can push it, pull it, and alter development to fine-tune its characteristics. Be warned: Once you shoot FP4 Plus, you might not want to use anything else.

Available formats: 35mm, 120, sheet

Kodak ColorPlus 200

Kodak

ColorPlus has already made our list of affordable films we love, so what’s it doing here? Well, this beloved cheapie film is also a classic: It was originally introduced in 1982 as Kodacolor VR, a color print film employing Kodak’s new “T-Grain” emulsion. In the late 1980s, Kodak brought out Gold and Ektar, both offering greatly improved color rendition. Rather than discontinue Kodacolor VR, Kodak rebranded it as budget-friendly ColorPlus and has been making it, virtually unchanged, ever since.

It’s that never-changed nature that makes ColorPlus a classic: As Kodacolor VR it helped to create the classic “film look”, and 40-plus years later it’s still delivering it—warm, slightly faded colors that make photos feel like fond memories. Beautiful grain, sharp detail rendition, and excellent latitude—not to mention a (relatively) cheap price—round out this oft-overlooked classic.

Available formats: 35mm

Kodak T-Max

Kodak

Kodak initially developed its “T-Grain” emulsion as a way to increase the speed and image quality of color films. In 1988 the company launched tabular-grain T-Max 100 and 400, the sharpest B&W films ever made with grain so fine it was practically invisible. Kodak followed on with T-Max 3200, a hyper-speed film that returned usable results as high as 12,500 ASA—heady stuff in the pre-digital era.

T-Max was a controversial film then as it is now: Some complained it was too flat, while others had trouble printing shadow and highlight detail, especially with T-Max 400. Many dismissed it as inferior to good ol‘ Tri-X. In truth, T-Max was (and is) less forgiving than traditional-grain films, and exploiting its ability to capture highlight detail requires more precision in shooting and development. And isn’t the need for precision one of the enjoyable challenges of film? Like Tri-X, T-Max isn’t for everyone, but it’s a film we think everyone should try—if for no other reason than to experience T-Max 100’s incredible resolution.

Available formats: 35mm, 120, sheet

Fujichrome Velvia 50

First introduced in 1990, Velvia is the slide film that toppled Kodakchrome 25 from its lofty perch as the standard by which color films were judged. Velvia was and is incredible stuff: Its fine grain is nearly invisible, even when projected at large sizes, and it produces bright, saturated colors that seem to explode off the screen. Unlike Kodakchrome, Velvia doesn’t require specialized processing, and it quickly replaced Kodachrome as the choice of professional photographers.

Velvia was reformulated in 2007, and the latest version still captures the detail and the colors of the original, plus it remains among the highest-resolution films available, rivaling digital for its resolution and color saturation. Slide film has become very expensive and is tricky to shoot—your exposure must be perfect—but a roll of Velvia is a special treat, if for no other reason than to see just how well film can perform.

Available formats: 35mm, 120

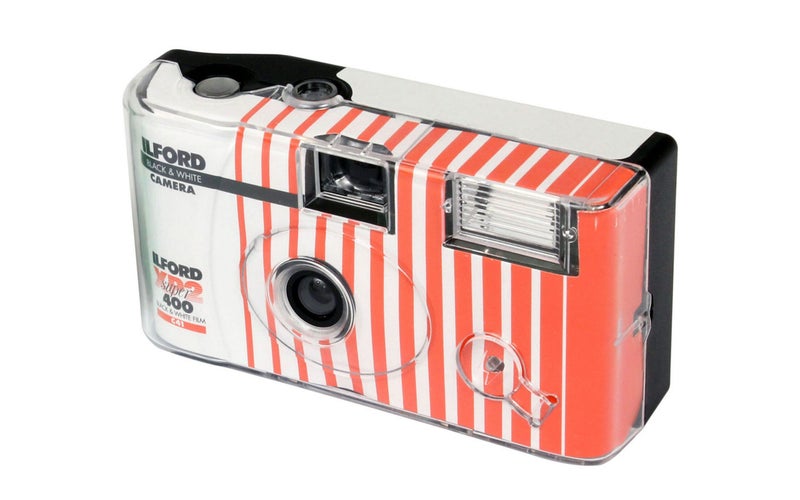

Ilford XP2 Super

Ilford

Introduced in 1980, the original Ilford XP was a novelty: A B&W film that was developed and printed using the C-41 color process. This was huge: In the 1970s, B&W film was largely the realm of students, artists, hobbyists, and pros. By making a B&W film that could be developed at the corner drug store, Ilford XP brought monochrome photography back to the masses. Forty-plus years later, XP2 Super is still doin’ its thing.

Today’s XP2 isn’t merely convenient: it’s also an excellent film with advantages that go far beyond ease of processing. Like other C-41 films, it has outstanding flexibility and latitude. While nominally rated at 400 ASA, XP2 can be shot anywhere between 50 and 800 with no alteration in development (though lower speeds may require post-production contrast adjustment). It produces excellent detail with contrast that is strong but not excessive. And because it’s a color film, it is compatible with Digital ICE software-based dust removal. XP2 Super is a film we recommend not for nostalgia, but for pure practicality.

Available formats: 35mm, 120, disposable camera

Fujifulm Neopan 100 Acros II

Fujifilm

Fujifilm is best known for its color films, but their Neopan Acros was a traditional B&W film with a strong cult following. While well regarded for its sharpness and range, Acros was best known for its resistance to reciprocity failure. Most films go a bit wonky when exposed for more than a second, requiring some form of compensation in exposure, but Neopan Acros could handle significantly slower shutter speeds without deviating from the metered exposure.

Fujifilm discontinued Acros in 2018, then did an about-face in 2019, announcing a new reformulated version of this beloved film called Neopan 100 Acros II. The resistance to reciprocity failure remains: According to the data sheet, Acros II can be exposed for up to 120 seconds with no exposure correction and up to 1,000 seconds (16.5 minutes!) with only an extra half-stop. Whoa! Given the reformulation, it might not be entirely accurate to call Acros II a classic film—but it’s doing the same job as the original, and that seems classically righteous to us.

Available formats: 35mm, 120

The post 8 classic films every analog photographer should try appeared first on Popular Photography.