Thus far, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has shown us the marvels of mountainous nebulas, broken down the composition of a steamy exoplanet, and documented a symphony of stars and galaxies. What’s next? How about some images from our own solar system? With the help of a citizen scientist, Webb’s freshly-released Jupiter photos are a marvel to look at. Here’s how they came to be.

Related: This is the deepest image of the universe ever shot

What you can see in the Webb Jupiter photos

The European Space Agency (ESA) shared two photos of Jupiter taken by JWST’s Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam), which is composed of three specialized infrared filters.

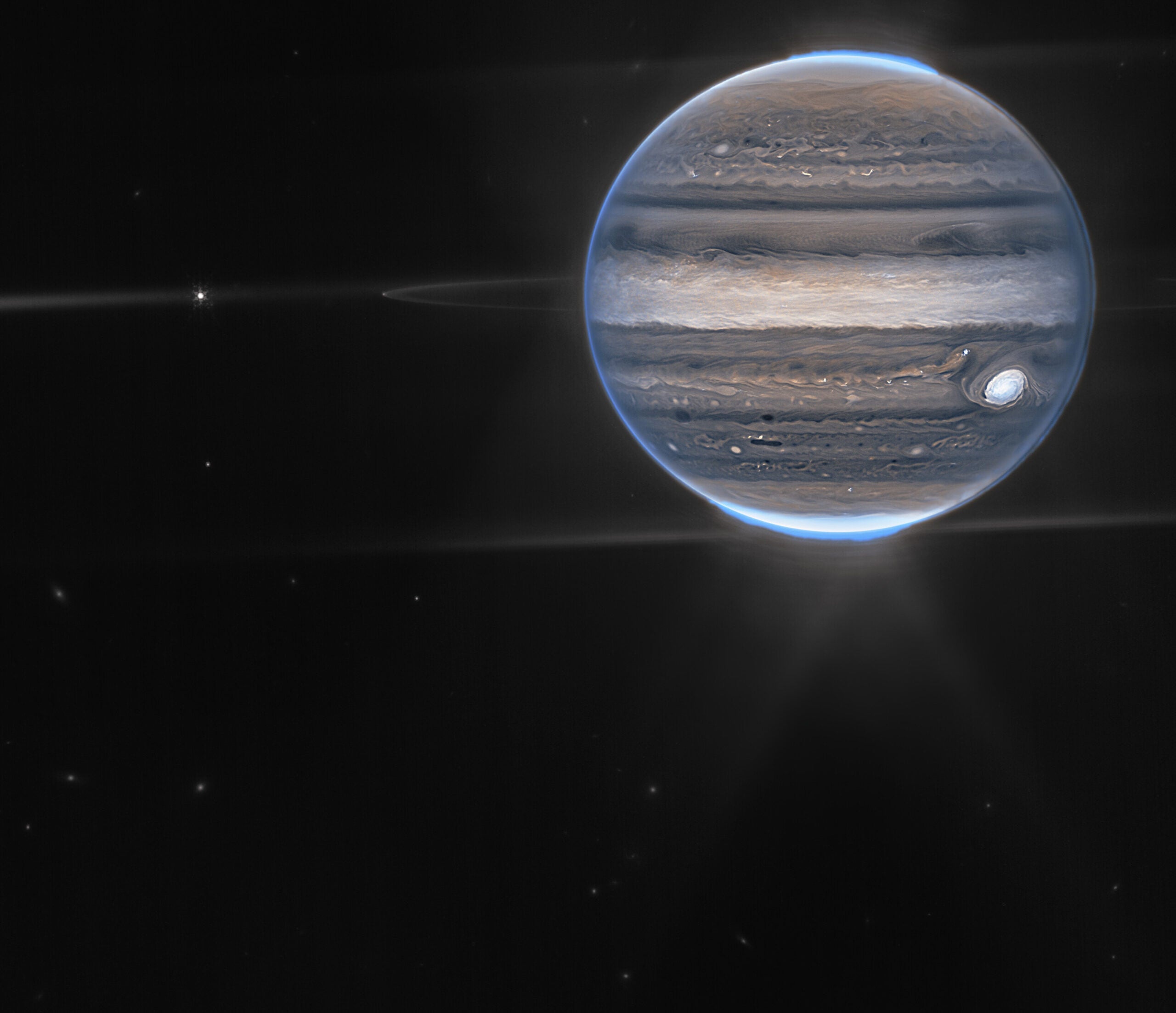

A wide-view image displays the planet’s rings, which are a million times fainter than Jupiter itself. Additionally, one can observe two minuscule moons: Amalthea and Adrastea. The lower plane of the image is dotted with what ESA describes as “fuzzy spots,” which it postulates are galaxies.

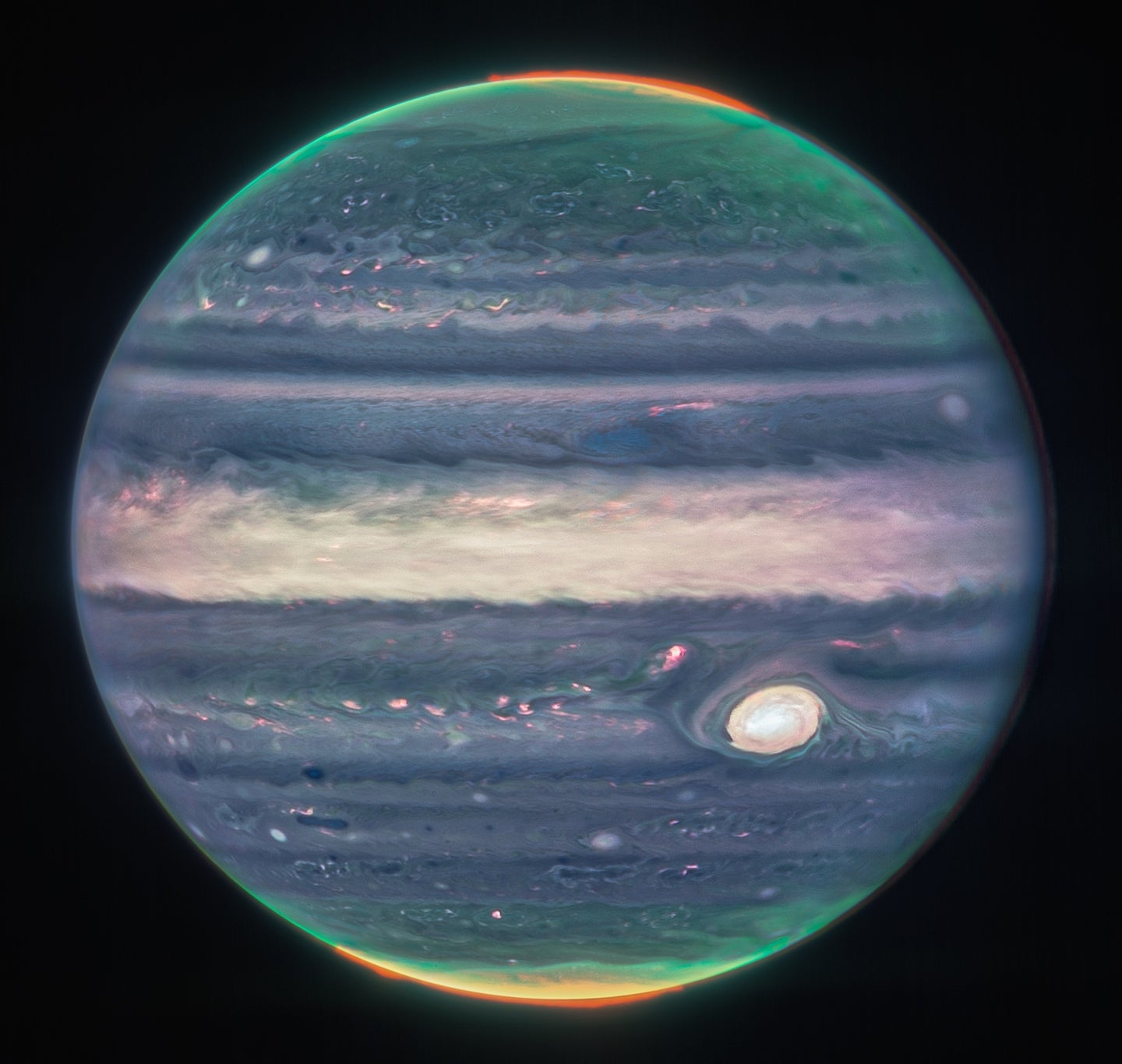

The second image is an up-close, personal view. Jupiter is known for its giant storms, gusty winds, auroras, and extreme temperatures and pressure, some of which are on display in the photo, a composite of several images.

Related: Webb’s latest ‘distant star’ photo is actually… a slice of chorizo

Observing the North and South poles, there are visible auroras, which have been interpreted in red.

“The auroras shine in a filter that is mapped to redder colors, which also highlights light reflected from lower clouds and upper hazes,” the ESA website reports. “A different filter, mapped to yellows and greens, shows hazes swirling around the northern and southern poles. A third filter, mapped to blues, showcases light that is reflected from a deeper main cloud. The Great Red Spot, a famous storm so big it could swallow Earth, appears white in these views, as do other clouds because they are reflecting a lot of sunlight.”

Translating infrared information into visible light

JWST’s NIRCam uses three specialized infrared filters, which gives it the ability to see incredible details. However, because infrared light is invisible to the human eye, it must be ‘mapped’ to visible light.

In this instance, JWST even had a little help from citizen scientist Judy Schmidt, who specializes in astronomical image processing, to create the renderings. Longer wavelengths are typically shown as red, while shorter wavelengths will appear blue.

The post A stormy Jupiter shines bright in Webb’s latest images appeared first on Popular Photography.