NASA successfully slammed a satellite into an asteroid yesterday, in a first-of-its-kind test of our planetary defense capabilities. Like something out of a blockbuster movie, the objective of the interstellar collision was to see if we can alter the trajectory of an approaching comet with a human-made object.

We won’t know if the experiment accomplished its goal for another two months. But the collision portion of the test was a resounding success. And best of all, NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) spacecraft sent back some really cool asteroid collision images, along with a video of its final moments.

What is the Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART)?

Related: A stormy, iridescent Jupiter shines bright in Webb’s latest images

NASA’s DART project is seven years and $325 million in the making. If that price sounds high, consider the fact that information gleaned from the experiment could one day save our planet from total or partial destruction.

The DART spacecraft, which was about the size of a four-door sedan, launched into space 10 months ago. Its ultimate target, an egg-shaped Asteroid named Dimorphos, is about 525-foot-wide. The goal was not to destroy Dimorphos—you’d need a much bigger spacecraft for that—but rather to nudge the big space rock enough to adjust its orbit around another, larger asteroid, Didymos (the two are considered “twin” asteroids).

“This really is about asteroid deflection, not disruption. This isn’t going to blow up the asteroid,” says Nancy Chabot, DART coordination lead at the Johns Hopkins University’s Applied Physics Laboratory. It’ll be a little while before we know whether or not the kinetic impact altered the asteroid’s trajectory. But if it did, it’ll be a huge accomplishment for science and humanity. And even if it didn’t, just making contact is a huge achievment in itself.

“DART’s success provides a significant addition to the essential toolbox we must have to protect Earth from a devastating impact by an asteroid. This demonstrates we are no longer powerless to prevent this type of natural disaster,” Lindley Johnson, NASA’s planetary defense officer, said in a statement.

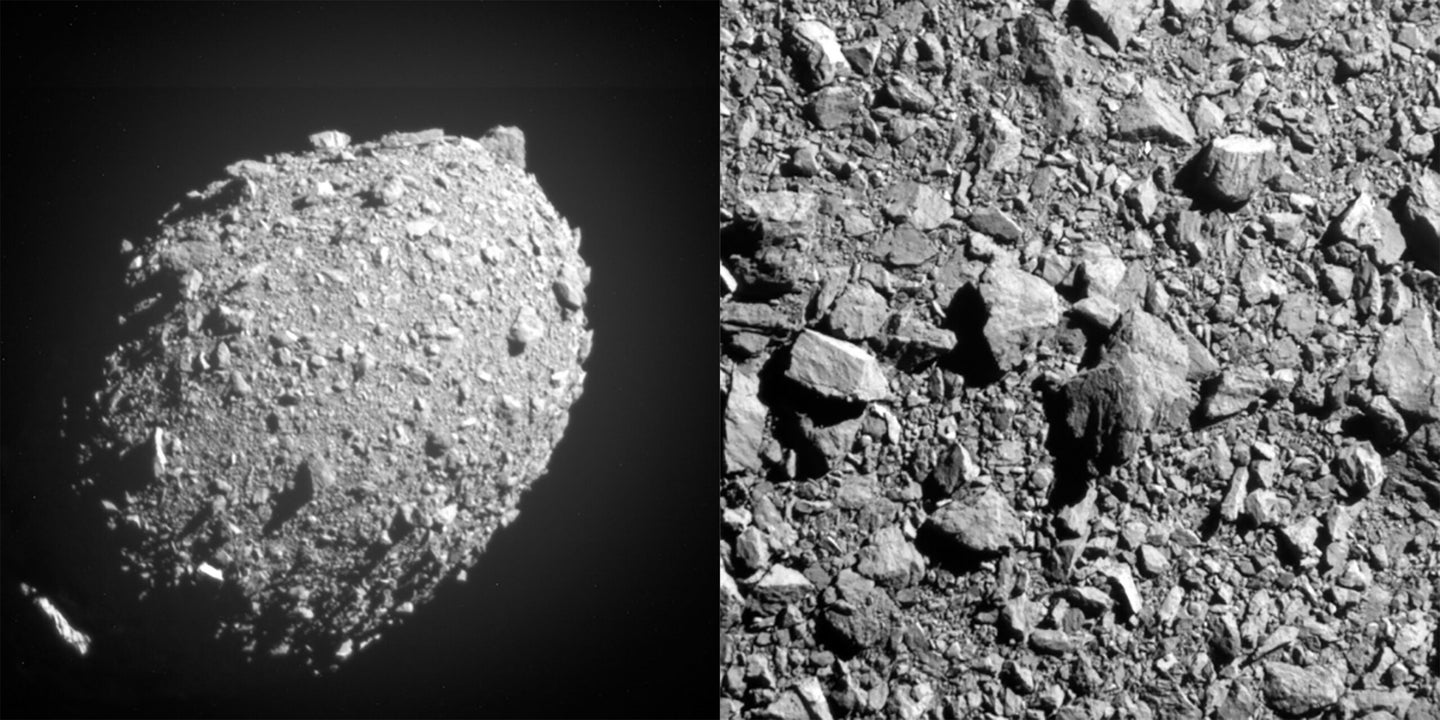

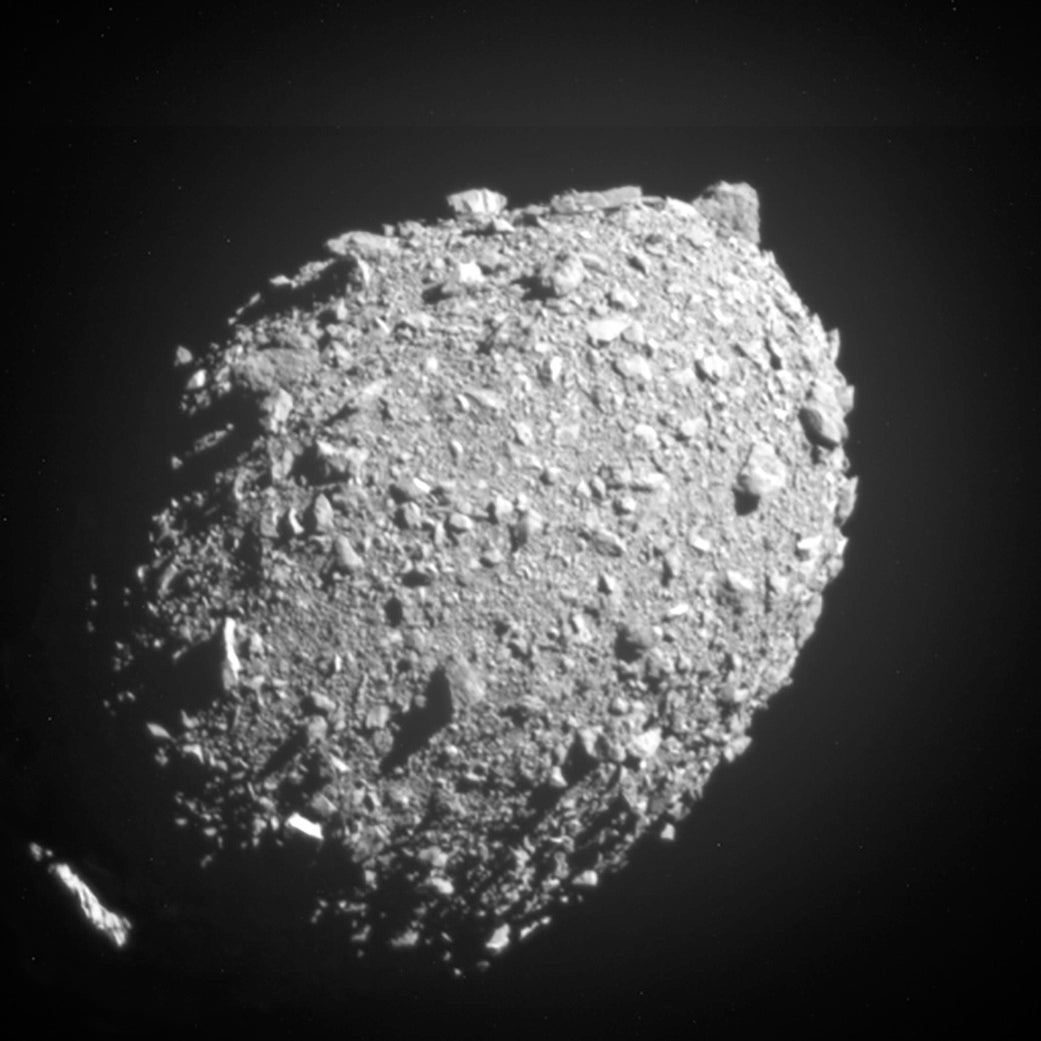

DART’s asteroid collision images

The DART spacecraft made contact with Dimorphos at around 7:16 p.m. Eastern Time on Monday, September 26. And thanks to the craft’s onboard “DRACO imager” camera, operated by Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Maryland, we got a front-row seat to that exact moment, which was also live-streamed to the public. See the video below.

Initially, the target of the collision was Didymos. But due to technical difficulties, NASA made a last-minute adjustment and instead crashed DART into Dimorphos at a leisurely speed of 14,000 miles per hour.

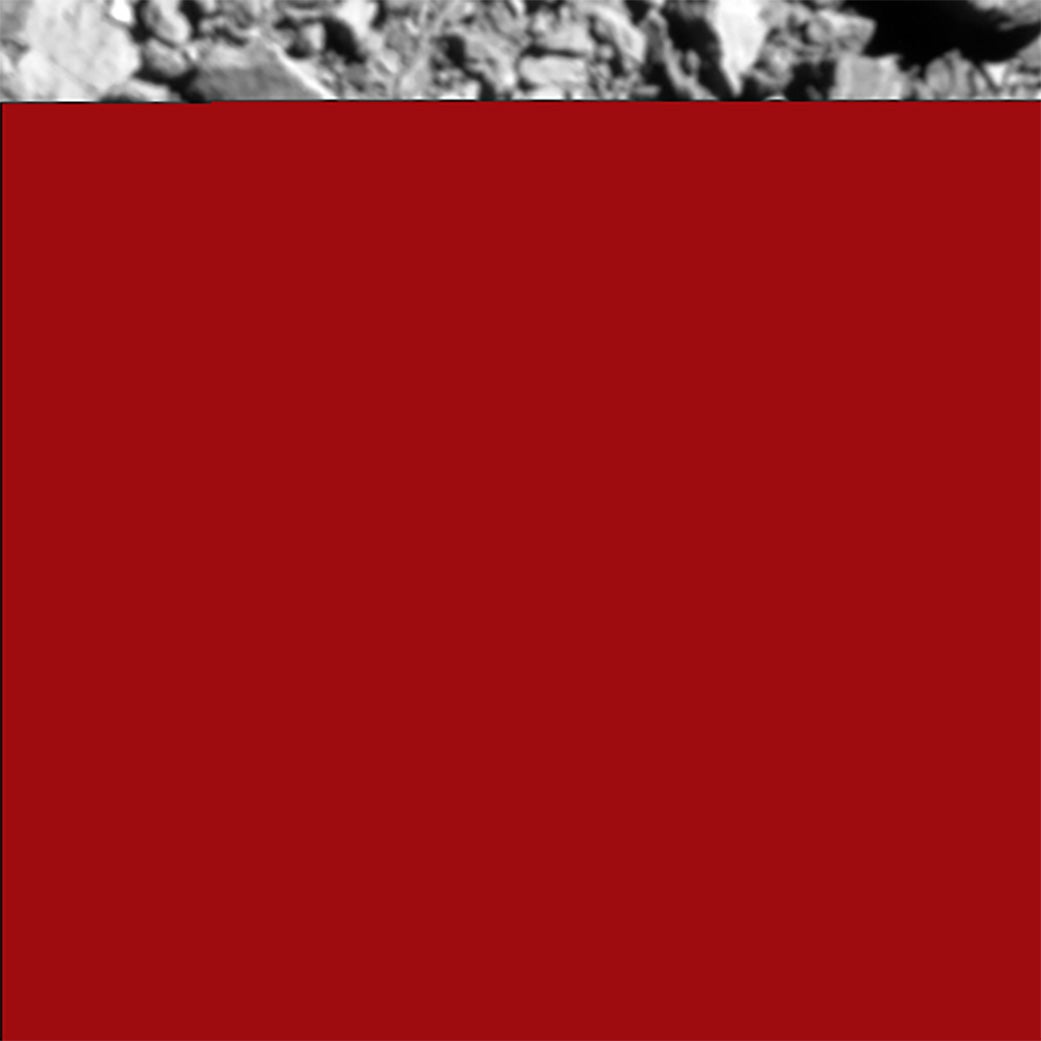

The last images show the spacecraft passing by Didymos with Dimorphos growing larger and larger in the frame until we see only its surface. And then, KABOOM, the final frame is nearly completely red due to the transmission cutting. According to NASA, that image was taken just four miles from the surface of the asteroid and one second before impact.

What’s next for DART?

It’s worth mentioning that Dimorphos and Didymos are more than 7 million miles from Earth and pose no threat. However, there are plenty of unknown objects yet to be identified by scientists, and at least some of these could potentially make contact with our planet. This is why the DART experiment doesn’t end with this initial impact.

Another smaller spacecraft was hanging around nearby to observe the collision. And countless land-based telescopes also witnessed the impact. While it may take a few weeks before we get additional views from space, videos from the ground are already circulating, like this one captured b the ATLAS asteroid tracking telescope.

Additionally, the European Space Agency plans to send up its hera spacecraft in the next few years to further investigate the aftermath of the test. This is all to say, expect more Asteroid collision images soon!

The post This is the last thing a satellite sees before crashing into an asteroid appeared first on Popular Photography.