This article is printed in the latest issue of British Journal of Photography magazine, Activism & Protest, delivered direct to you with an 1854 Subscription.

Drawing on the experiences of 22 women in 20 countries, a recent study illustrates the issues faced – and the acts of resistance carried out – by practitioners across the Global South. Brenda Witherspoon and Saumava Mitra report

Across the Global South, women working as photographers for international media are dismantling systemic practices. These practices can strip people of dignity, overemphasise stereotypical perspectives and undermine their work as professionals based on their gender, race and nationality. They resist along a spectrum of impact and consequence. They leverage scraps of power to shape narratives. Sometimes they walk away. “I prefer to have less work but have it right because I feel like this is something that needs to change. And I know that change is going to take some time and some sacrifices,” says a woman working in Asia who did not want her name used because of safety concerns.

A research study we recently completed explores these acts of protest by drawing on the experiences of 22 women from 20 countries whose work is known internationally. We found that strong inner compasses guide their interactions with photographic subjects and industry gatekeepers alike. They offer a model of respect for these subjects and demand – but don’t often receive – respect from their editors, especially those with less cultural competence. However, they remain determined to challenge what they see, and make the changes they envision despite the many barriers. “I still have a voice. Even though my voice is just in my small circle of 20 to 30 people, it is still a voice. And they are words; they are images,” says a woman from the Middle East/North Africa who took part in the study. “It is a snowball effect. It will grow, and this is how… change happens.”

All but two of the women we interviewed in 2020 for the study, which granted them anonymity, have ties to the Global South; most of them live and work there as photographers. The woman from Asia mentioned in the introduction was interviewed separately following the research, as were several others who spoke on the record. Their actions echo the forms of resistance described by those in the study: countering stereotypes and, when called for, refusing to bend to undue demands. In their struggles to earn respect for themselves, they position respect for those they photograph at the centre of their work.

Dismantling stereotypes

Imagery fed to international audiences amplifies stereotypes about places and people in the Global South because market forces are at play, says Bertan Selim, head of programmes at the Prince Claus Fund, which helped set up the Arab Documentary Photography Program. “The example that always gets pushed down people’s throats is a western one. That’s by default, whether it be how you do research or how you photograph or how you talk about events or how you create sellability out of a story,” says Selim. And what sells in the international media is often trauma and poverty.

Indeed, those primarily based in their native countries and who spoke to us for the study are very aware of what images appeal to international audiences, compared with the work they make for local audiences. Photographer Verónica Sanchis Bencomo founded the platform Foto Féminas to uplift the work of Latin American and Caribbean female photographers, including, most recently, London-based Venezuelan photographer Silvana Trevale and French-Peruvian photographer Florence Goupil, who is based in Peru. Sanchis Bencomo moved from Wales to Santiago, Chile, to do research and gained “a very different perspective”. She began to question why it was so hard to find content created by Latin American women, inspiring her later efforts to connect international audiences to that content.

Women throughout our study also described the photographic field as male-dominated, mobilising their distinctly female and local perspectives as balancing tools. “I realised the image of the women coming from my country were mostly from… a foreigner’s perspective and a male perspective,” says the anonymous photographer working in Asia. “So I wanted to come back to my country to focus more, and work on longer and deeper work on women, to show the life of women in the country from a female perspective.”

Meanwhile, Sagal Ali, founder of the Somali Arts Foundation, regards the organisation’s Still Life exhibition as sending subversive messages at every level. The show spotlighted the work of two female photographers – Fardowsa Hussein and Hana Mire – in an otherwise male-dominated industry. “[The exhibition] was the first of its kind in Somalia… it broke stereotypes – the [artists] are women, [the show was] curated by a woman, myself,” Ali says. “So the whole experience went against the dominant view of women, particularly women doing a professional job.”

However, before photographers in or with ties to the Global South can counter stereotypes in their work, they must first have access to jobs, and stereotypes often limit that access. The Arab Documentary Photography Program, which amplifies creative approaches to visual storytelling that challenge conventional narratives about the region, wanted to counter that from the outset. “There was a huge bias that there is no quality and that one was always forced to fly people in and have stories covered in that sense,” Selim says. “There’s also an inherent sort of laziness in activating networks and looking for people. It’s also not necessarily very cost-effective, and it takes time too.”

A woman in the study from Southeast Asia points out the absurdity of such an approach when someone needed a photo of a hotel in the city where she lives and works. “It was again by some white photographer, and I thought, ‘My gosh, you flew somebody out here with a huge carbon footprint to take a photo that anybody [here] could have taken,’” she says. “It is still frustrating and anxiety-inducing as someone who is emerging, who is a woman, and who is a person of colour, and you think, ‘What chance do I have of getting my foot in the door?’”

Tahmina Saleem, an Afghan photographer, interviewed three weeks before the fall of Kabul, said international media were aware of award-winning Afghan photographers but preferred to spend extra money instead of hiring local women. Meanwhile, in-country media protested the costs of hiring women – such as separate rooms and security. “It hurts you,” Saleem says. “You want to work. You want to work across Afghanistan; you want to cover across Afghanistan. But people are judging on their own that you can’t go to these areas, and they don’t give you the opportunity.”

The photographers value their intimate knowledge of where they are from and say it results in better-quality work in those locations. “We are living in this situation every day. We are seeing what is happening in the streets, more than anyone from outside coming and staying for a month or two who hasn’t seen the history, who hasn’t seen the insides, who doesn’t know the local language or understand the nitty-gritty of things,” says a photographer from the Middle East/North Africa.

Indeed, many women in our study brought up the role of gatekeepers in London, New York or Paris on behalf of western media organisations. One from sub-Saharan Africa specifically noted a preponderance of white men. “It goes higher than just the photographers on the ground. It’s obviously systematic,” she says.

Saying no to work

Working within a given system has limits. Our study participants and the others interviewed described simply saying no to unacceptable assignments as a form of resistance while acknowledging that it’s not that simple. “If you are dealing with a platform that is so used to one kind of image, it’s not easy to tell them that this different picture needs to be seen as well… You end up losing a lot of opportunities,” says the woman from Asia with safety concerns. Indeed, sometimes negotiations go nowhere and saying no is the only option.

However, the privilege of refusing more often falls to those not from the countries in question, as two photographers in the study who hail from the Global North exemplified. One from Europe said she eventually began refusing fly-in, fly-out assignments and asking those seeking to hire her to instead choose from among the qualified local photographers.

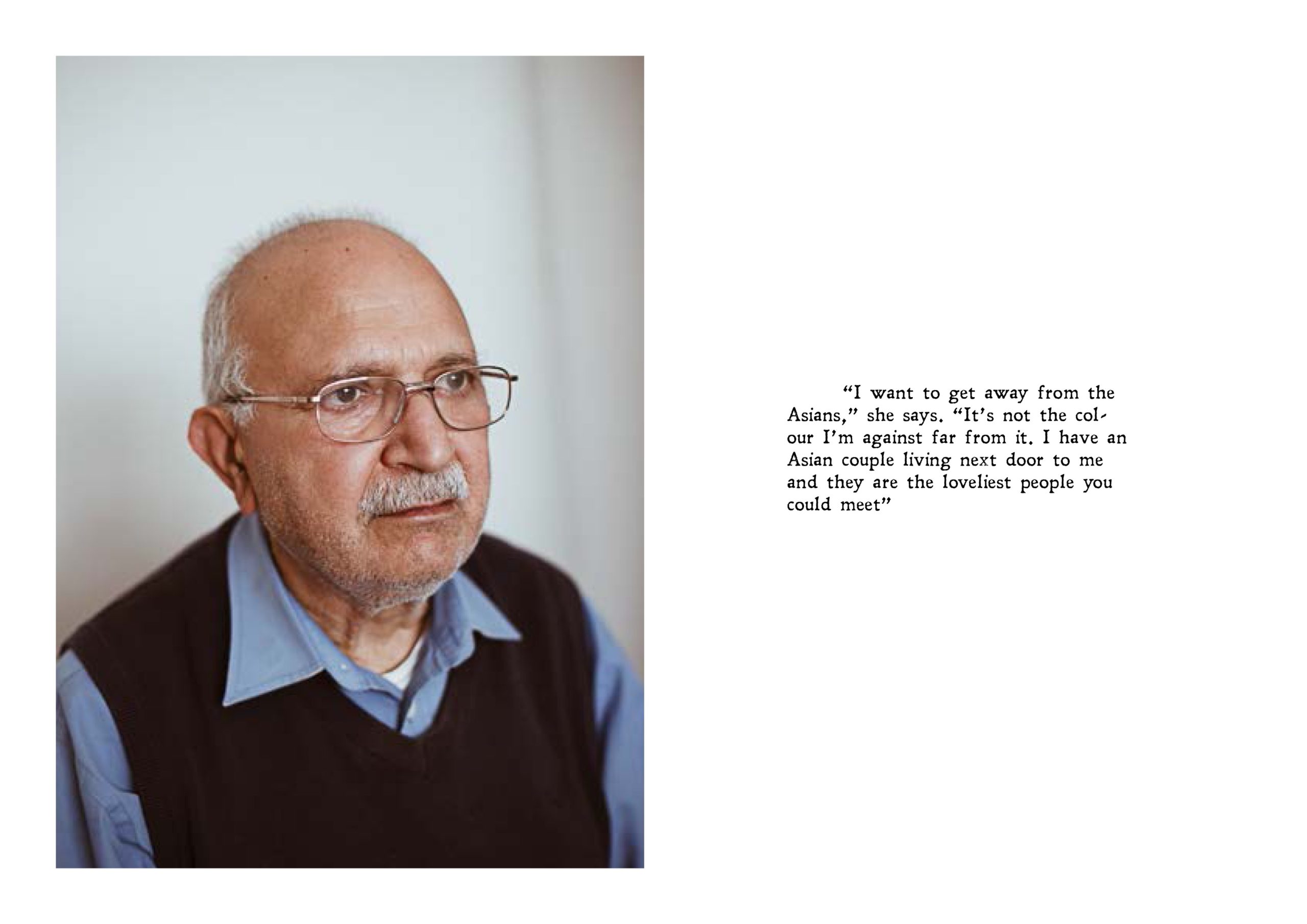

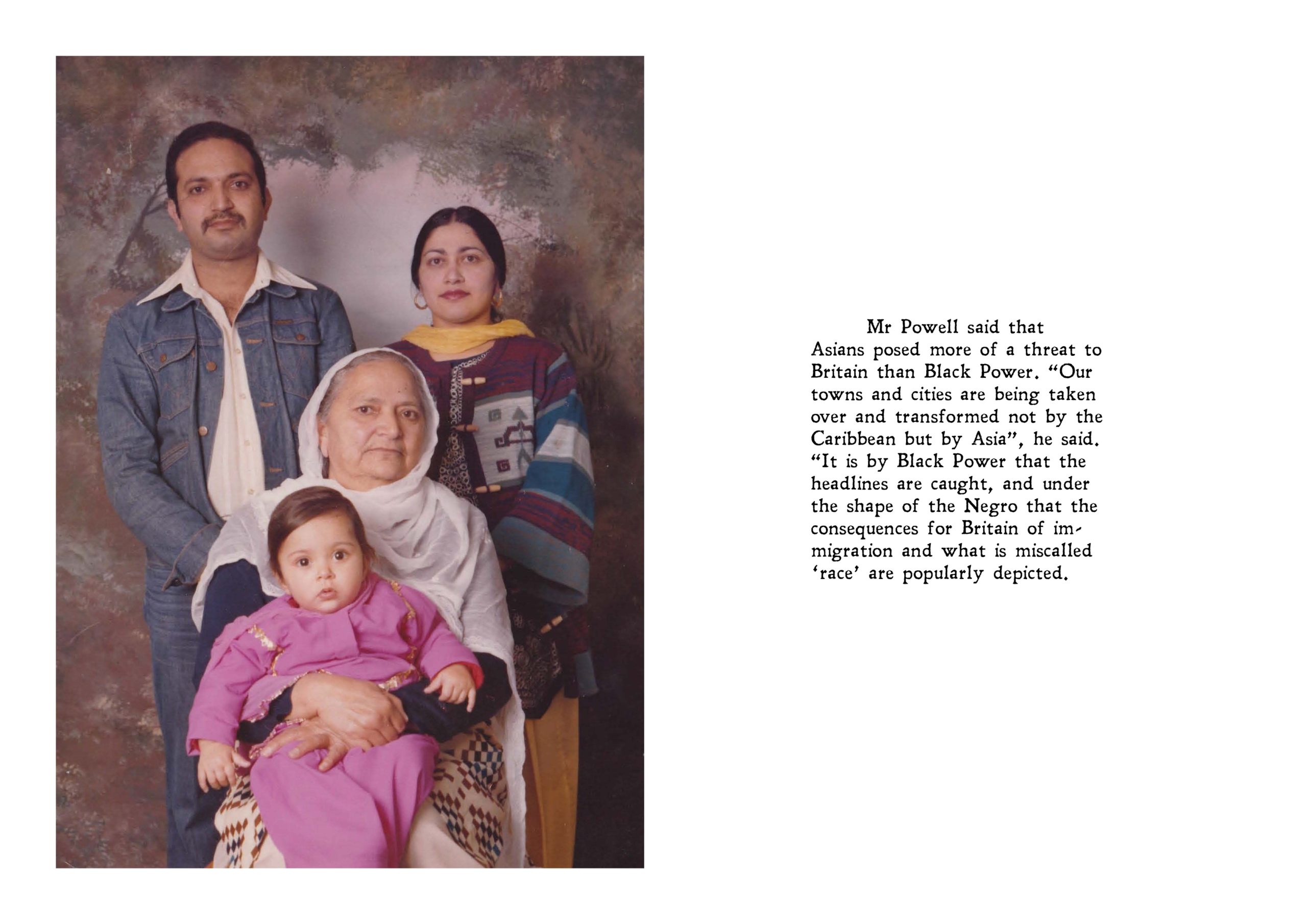

Shaista Chishty, who is based in London and is British with Pakistani heritage, echoes such acts of refusal. She worked as a photographer in Africa, Asia, Europe and the Middle East, but walked away from the industry to pursue an MA focusing on representation and still struggles to process what’s even possible for photographers to accomplish. “I’m still working things out. So my website is still there, and I cringe,” she says. “I should probably take it down because I feel that it just perpetuates an unhelpful narrative.” The work featured here offers an insight into her new approach. The series Five Pounds in My Pocket, for instance, explores the stories of Pakistani people who moved to Birmingham, UK, from the 1950s to the 1970s. The ongoing dehumanisation of ‘migrants’ in the mainstream media inspired it, and in contrast to the straightforward documentary style of her earlier work, this series collates interviews, portraits, and personal archives to explore the stories of several people who arrived in the UK with just a small amount of money to their name.

A violent and intrusive act

Infusing dignity into their photographic work is central to the women participating in the study and outside of it. They are aware of the “violent and intrusive act” they must commit when photographing people whose dignity has rarely been considered by photographers making documentary and photojournalistic images, a woman from the sub-Saharan Africa region observed.

She and others spoke about seeing bodies of people of colour depicted in ways seen as unacceptable for individuals from other regions. A second woman from sub-Saharan Africa envisioned what coverage of a death from Ebola might look like in the United States. “They would show that this person is dead, but they wouldn’t show us the body,” she asserts, noting the contrast with an image she saw in an internationally renowned current-affairs magazine from the US. “[There] is a man who’s dying. The family would [probably] find out that this person is dead through this image. The person was not covered. Their face was not covered. There was no dignity in the coverage. And this was masqueraded as a beautiful image.”

The photographers in the study are hyper-aware of the power they hold behind the lens. “If you are a journalist, it is intrinsically a very imbalanced relationship,” one participant from Southeast Asia observes. “The photographer is always, always, always in a position of privilege. Yes, you can narrow the gap, but I don’t think you can ever close it, especially as it is the photographer who always has the choice to leave in an uncomfortable situation.”

While Chishty says she “always tried to work ethically”, picturing how she would treat her relatives, she nonetheless finds much of her previous work problematic. “There’s one image in particular which haunts me,” she says, describing a picture of a woman in Sudan she made on behalf of an NGO. “She looks striking because of the colours in the image. And she’s holding her baby, and she’s looking directly into the lens.” Today she reads resentment in the woman’s face. “How much agency was she afforded in making that decision to be there?” Chishty continues. “I feel upset that I subjected this woman to this. And her image, unbeknownst to her, probably ended up in all these different places.”

The woman working in Asia has found the best answer to difficult situations is putting down her camera – at least sometimes. “I was in one of the provinces, and this woman was put to the fire by her in-laws. And I went there, and she was not comfortable with showing her face and having her picture taken with the entire face,” she remembers. “I realised, she’s so keen to talk about her story. And I was like, ‘It’s OK if I don’t take pictures, let’s just sit and listen to her’.”

From collisions to collaborations

Our study and conversations show that women working as photographers in the Global South constantly collide with the practices and approaches of editors, publications and curators. The situation incites them to take a range of actions – from refusing to become collaborators in what they see as unfair practices to seeking out collaborations to change and challenge accepted ways of doing things. But progress can be hard to measure, and it is not uniform across countries.

Regardless, Sanchis Bencomo has observed a definite improvement in the photography industry in Latin America since 2017. “There are more platforms now promoting photographers from Latin America”, compared with when she started Foto Féminas, she says. She is also encouraged by a new wave of collectives and festivals. Ali has also observed progress as the Somalia Arts Foundation grows into a community serving members’ needs beyond her initial vision. Meanwhile, Selim recognises the Arab Documentary Photography Program as having leveraged energy already present in the region: “It’s really about understanding that that was already there. We never really created something that appeared all of a sudden.”

But photographers note more regression than progress in areas where active conflict disrupts security and opportunity, such as Afghanistan. Nevertheless, some not only persist but double down on their commitment. “It gives me hope that, OK, I should continue,” says the woman in Asia who put down her camera to listen. “You know that there’s a possibility that you can do something. How can you resist that?”

The post Female photographers across the Global South reflect on the challenges they face appeared first on 1854 Photography.