This article is the first in a mini-series, In Search of Ourselves. We speak to three artists – Ana Vallejo, Bowei Young and Andre Ramos-Woodard – about vulnerability and trauma, and how they use the camera to gain a better understanding of themselves.

In her latest project, the Colombian artist charts her pursuit to untangle the relationship between trauma and intimacy

It is possible that we have all given anxious thought to what would happen if we could release our pain and trauma. If we could resist our instinct to hide, or disguise our shame and discomfort, and have people say, “I feel it too”. Historically, image-making has been employed as a strategy to make sense of ourselves. Look no further than Nan Goldin’s The Ballad of Sexual Dependency – iconic work that radically altered our understanding of photography and the possibilities the medium has to offer. Unlike so much photography that maintains distance, Goldin’s images are up close, honest and searingly personal.

Now, a new generation of photographers are using the camera to take a sharper look at the human condition, grappling with the precarious positions of racism, homophobia and mental health. This willingness to confront complex realities offers a counter-narrative to the toxic optimism that proliferates in current mainstream culture. The work is not limited to facing personal trauma, although it does with brutal force. It also occupies a sense of communal yearning.

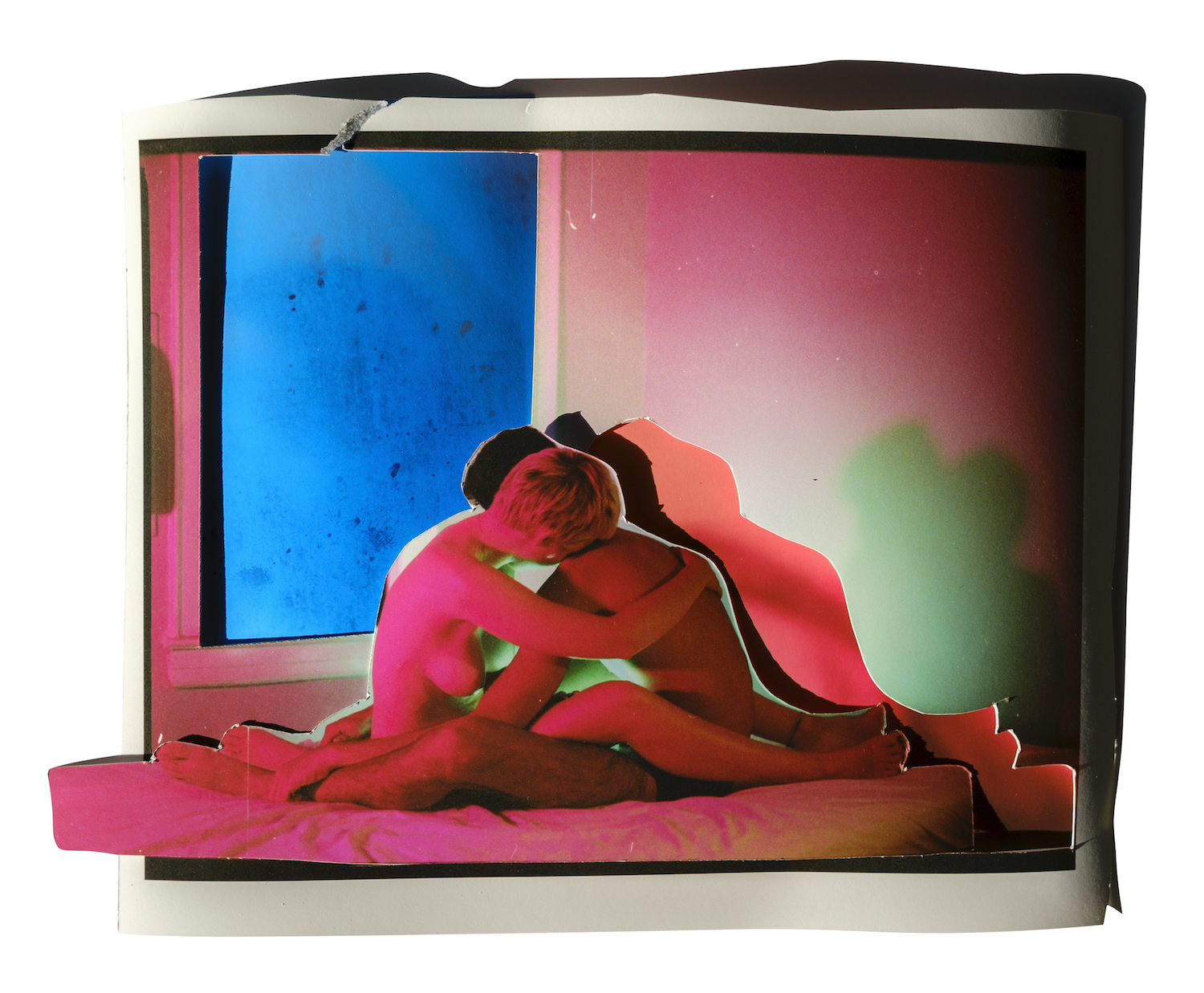

In Neuromantic, Ana Vallejo grapples with the psychological landscape of “love addiction”. The Colombian artist charts her pursuit to untangle the relationship between trauma and intimacy. As a self-confessed “love addict”, Vallejo uses the project to confront herself while activating a mutual relationship with the viewer: a space for acceptance, healing and new beginnings.

“Love became a way to dissociate from reality. A fantasy that, although it would often hurt me, would soothe my anxiety and stress. When I began to look around, many friends and ex-partners also used love as a coping mechanism.”

“I’ve always felt like an outsider,” says Vallejo. The artist’s early life was consumed by mental illness: her father was diagnosed with schizophrenia shortly after she was born, and suicide and anxiety haunt her family. “I’ve done many extreme things to gain someone’s attention,” she explains. “Love became a way to dissociate from reality. A fantasy that, although it would often hurt me, would soothe my anxiety and stress. When I began to look around, many friends and ex-partners also used love as a coping mechanism. Through this work, I want to engage in conversation and connect with people who have had similar abusive and traumatic experiences to mine.”

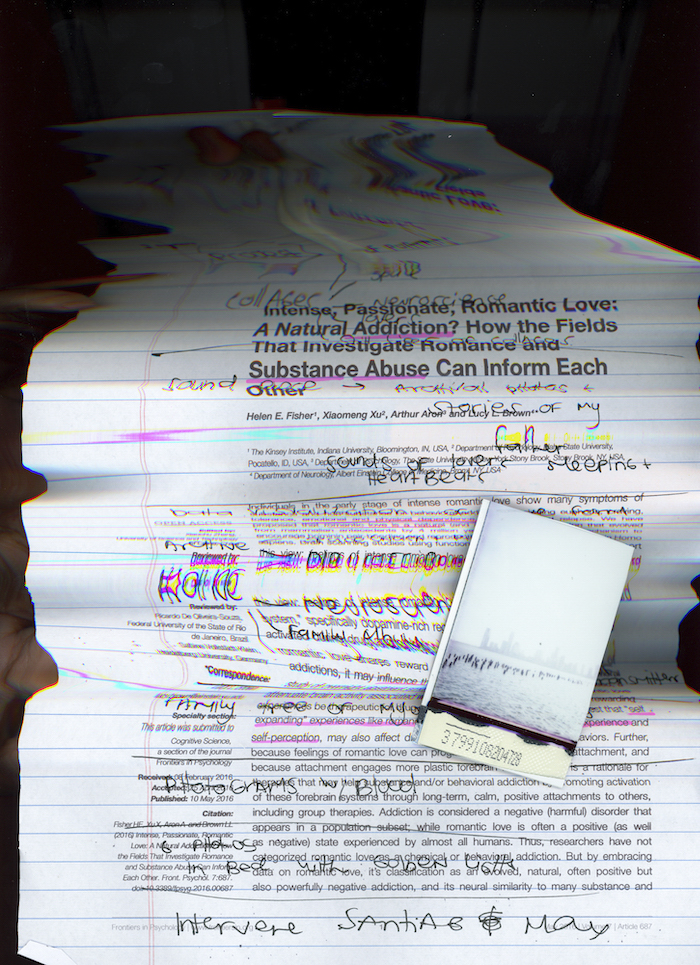

Through multilayered, experimental portraiture, Vallejo creates a portal, accessing complex and challenging emotions that have long been buried or denied. Working with friends, past lovers and her own body, she visualises the chaos of love addiction, capturing the extremes of pleasure and pain. Images are heightened by a bright palette and visual disruptions – including burning and blur – enabling her to transcend reality and create a visual language around her emotional journey. Vallejo insists on the possibility of healing by grounding the project in scientific research. She traces the connection between addiction, trauma, abuse and how they manifest in our attachment styles. These findings become work in and of themselves. Integrated through collage and text, they shed light on decades of struggle.

Over time, Neuromantic has transitioned from visual art to an interactive experience. Through collaboration with data scientist Andrew Hill, Vallejo has launched anonymous surveys where the public can share their experiences and become part of the work. Together the pair will use the data to trace collective behaviour patterns as well as nuanced individual traits.

“Connecting with the viewer is one of my priorities. I want the project to resonate with people going through difficult intimate situations and offer them tools and knowledge. I hope it becomes a safe place to share and vent. In those interactions, knowledge and empathy are exchanged.”

The post Ana Vallejo grapples with the psychological landscape of love addiction appeared first on 1854 Photography.