Vikesh Kapoor’s mother delivered over 3000 children throughout her career as an obstetrician-gynaecologist in Lock Haven, Pennsylvania. The artist’s new series, commissioned by Leica, in collaboration with 1854, reflects on that history.

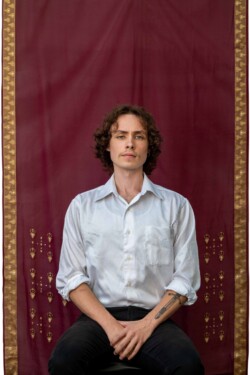

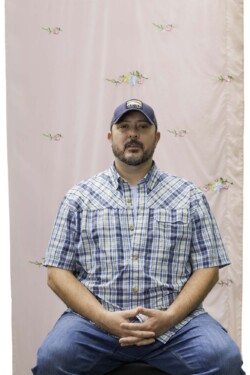

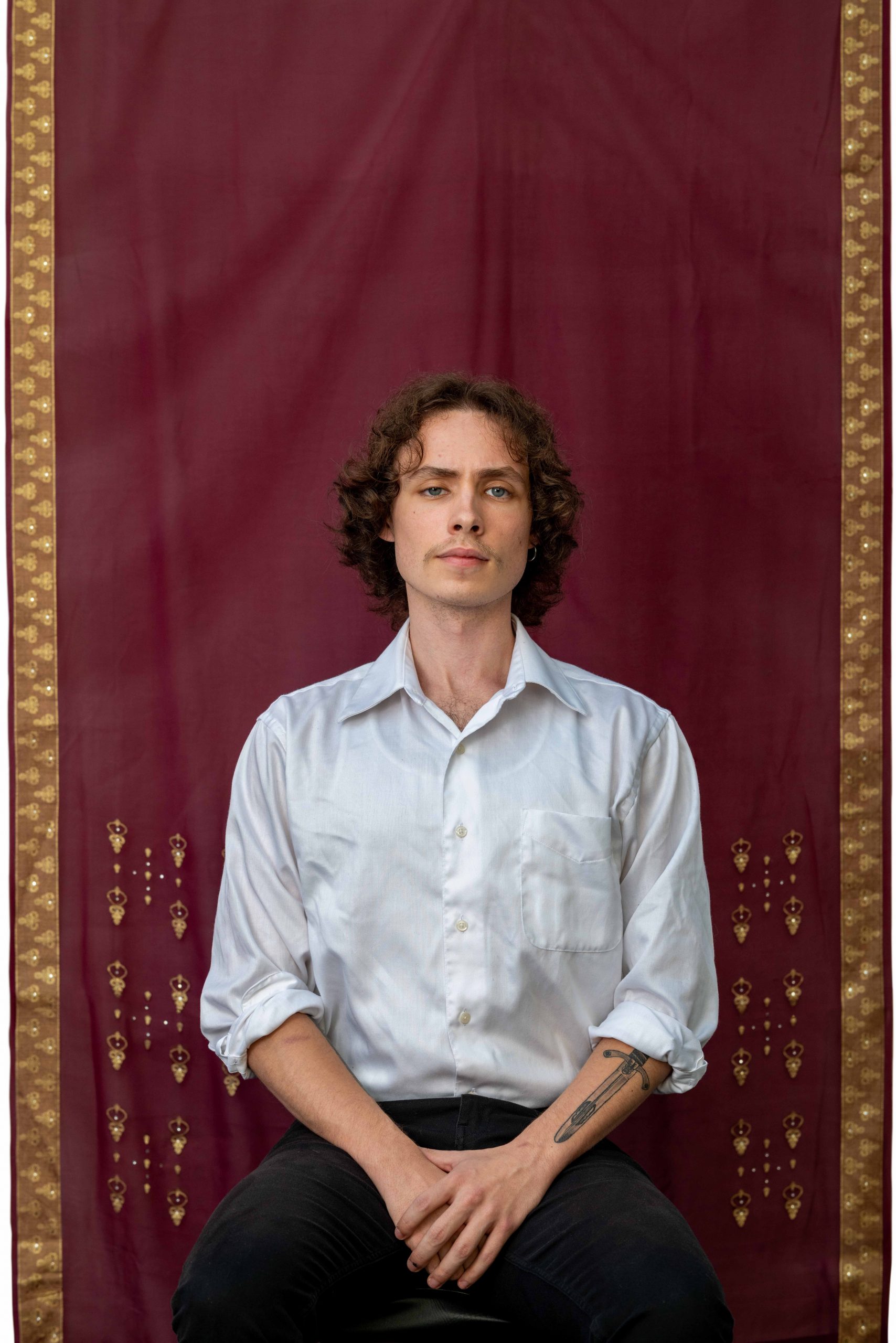

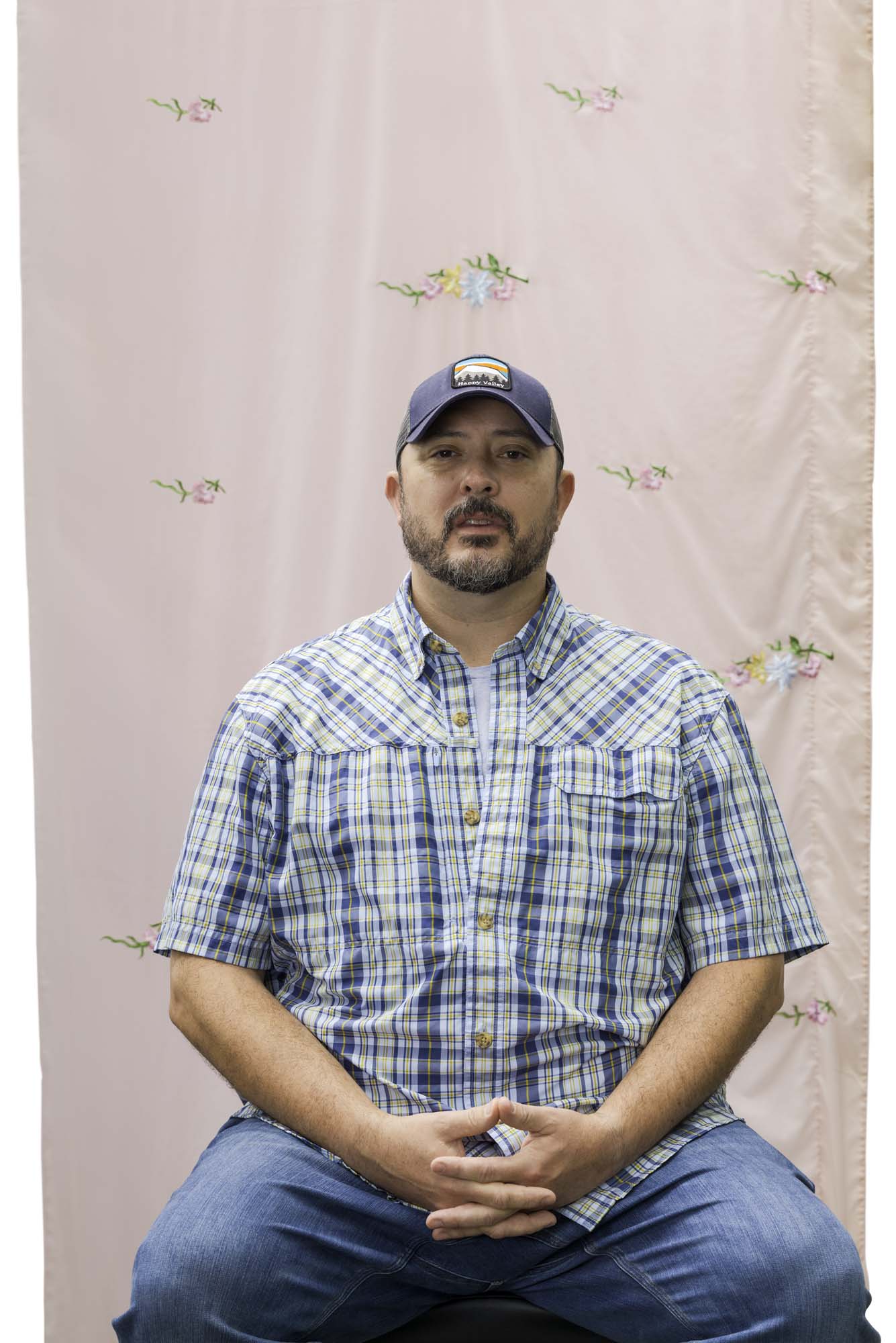

An unexpected installation occupies a library car park in the city of Lock Haven, Pennsylvania. Bright saris slung across the back of a makeshift photography studio: bursts of colour punctuating an otherwise unremarkable swathe of grey. Various individuals pass through. An Emergency medical technician officer arrives, posing for a portrait against a burnt orange sari. Later, two brothers sit for a photograph — an intricate expanse of fabric embroidered with golden petals stretching out behind them. Multidisciplinary artist Vikesh Kapoor stands next to a camera, engaging his subjects and easing them in. To an outsider, the set-up might seem random. However, it is far from it. Kapoor’s mother, a now-retired obstetrician-gynaecologist, helped many of the subjects deliver their babies. And the remaining sitters were once those babies themselves — the portraits comprising one facet of a new project expressing the artist’s devotion to his mother, Sarla Kapoor, and her commitment to her profession.

“She was devoted to her work”

-Vikesh Kapoor

“She was devoted to her work,” says Kapoor of his mother, who delivered over 3000 children while working in the rural Pennsylvanian city. However, Lock Haven was not always her home. Sarla emigrated to the US from India in 1971 (along with his father, a now-retired doctor), initially settling in New York before moving to Pennsylvania. The artist’s first project, See You At Home, responds to that history. Through observing his parents, Kapoor examines the loss and isolation immigrants may experience growing old in a non-native culture. His new project continues that familial thread. Commissioned by Leica, in collaboration with 1854, Kapoor created the work in response to the theme Witnesses of: Devotion, celebrating his mother and her profession. Kapoor shot the work entirely on Leica equipment, ‘It was a joy to work with the Leica SL2 and its accompanying lenses for this commission. Normally I use handheld rangefinders, but for this project I utilized the camera’s LCD screen in tandem with a tripod when composing my photographs. This process allowed me to freely engage with my subjects when making this set of portraits, instead of hiding behind a little viewfinder.’

Kapoor was not always a photographer. He started as a musician, releasing his debut album, The Ballad of Willy Robbins, in 2013. However, his mother’s health overshadowed his success: the day following the record’s release, Sarla (who retired in 2011) underwent heart surgery. “In between tours, I would visit her in the hospital,” he remembers. “Her recovery was difficult.” The situation incited Kapoor to reflect on the sacrifices she had made for him and the love and support she’d provided his entire life. His photographic practice, notably See You At Home, developed from this period of reflection. However, while that initial series encompassed both parents, Kapoor’s current work is a homage to his mother alone.

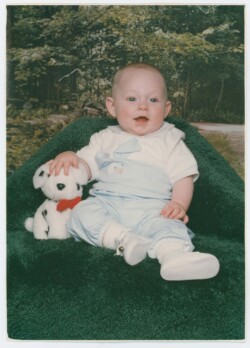

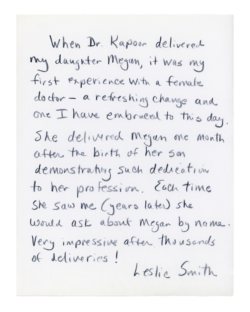

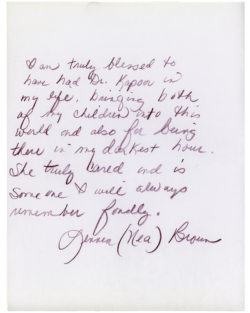

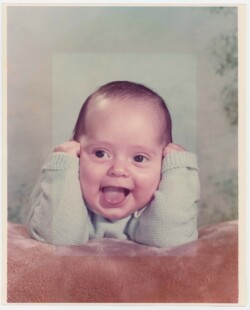

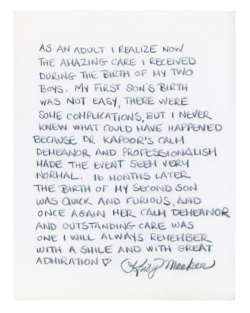

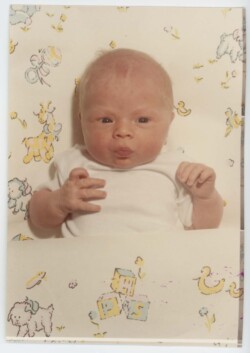

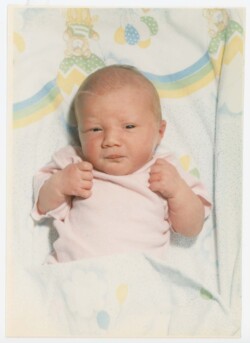

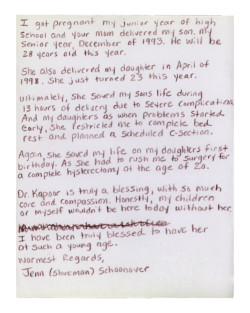

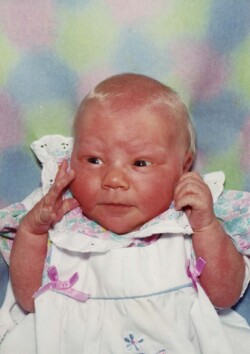

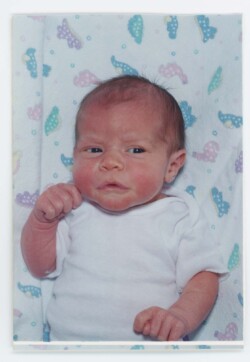

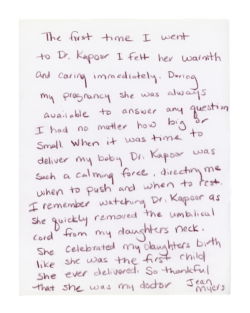

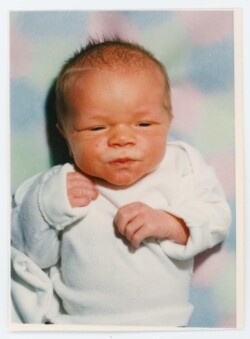

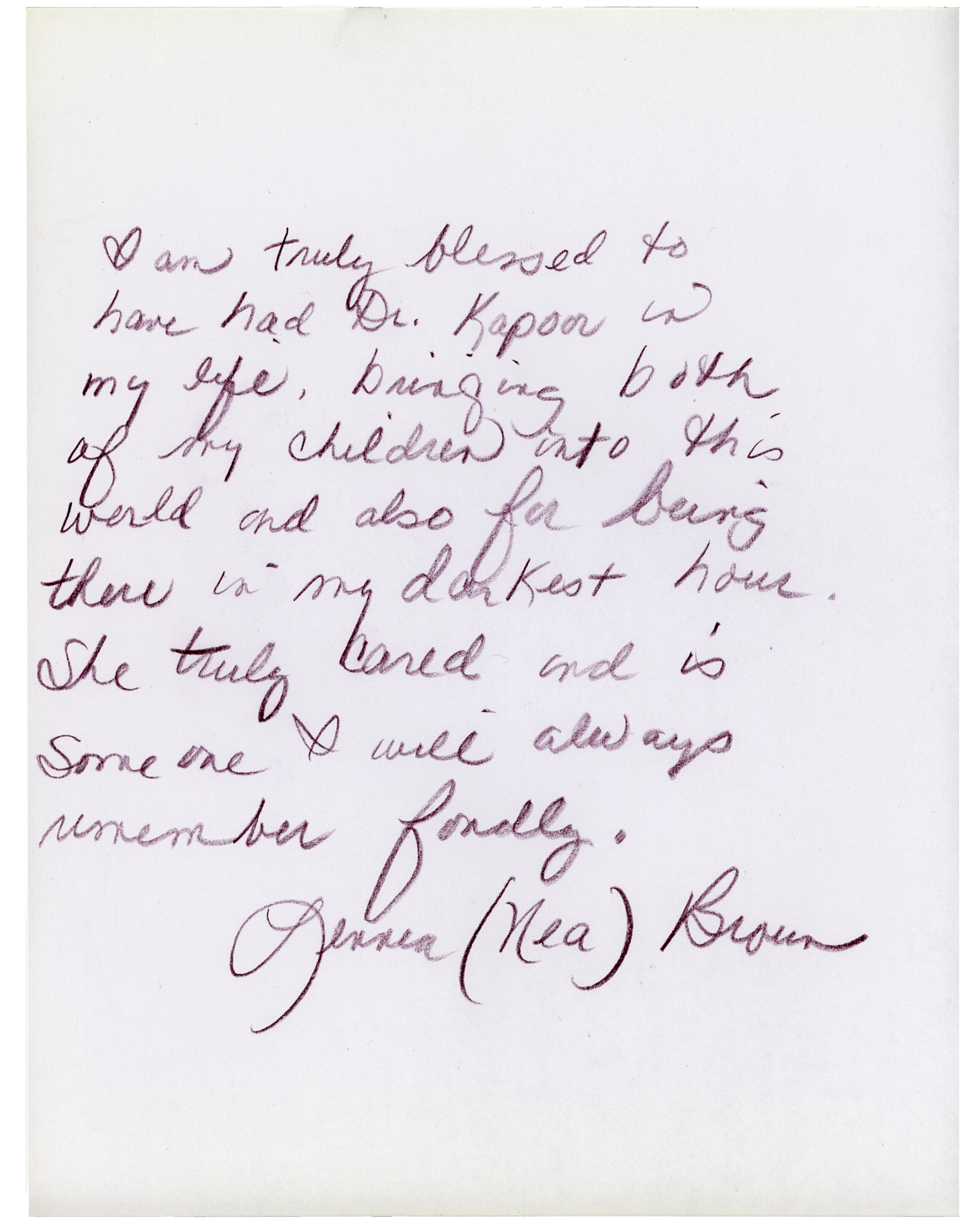

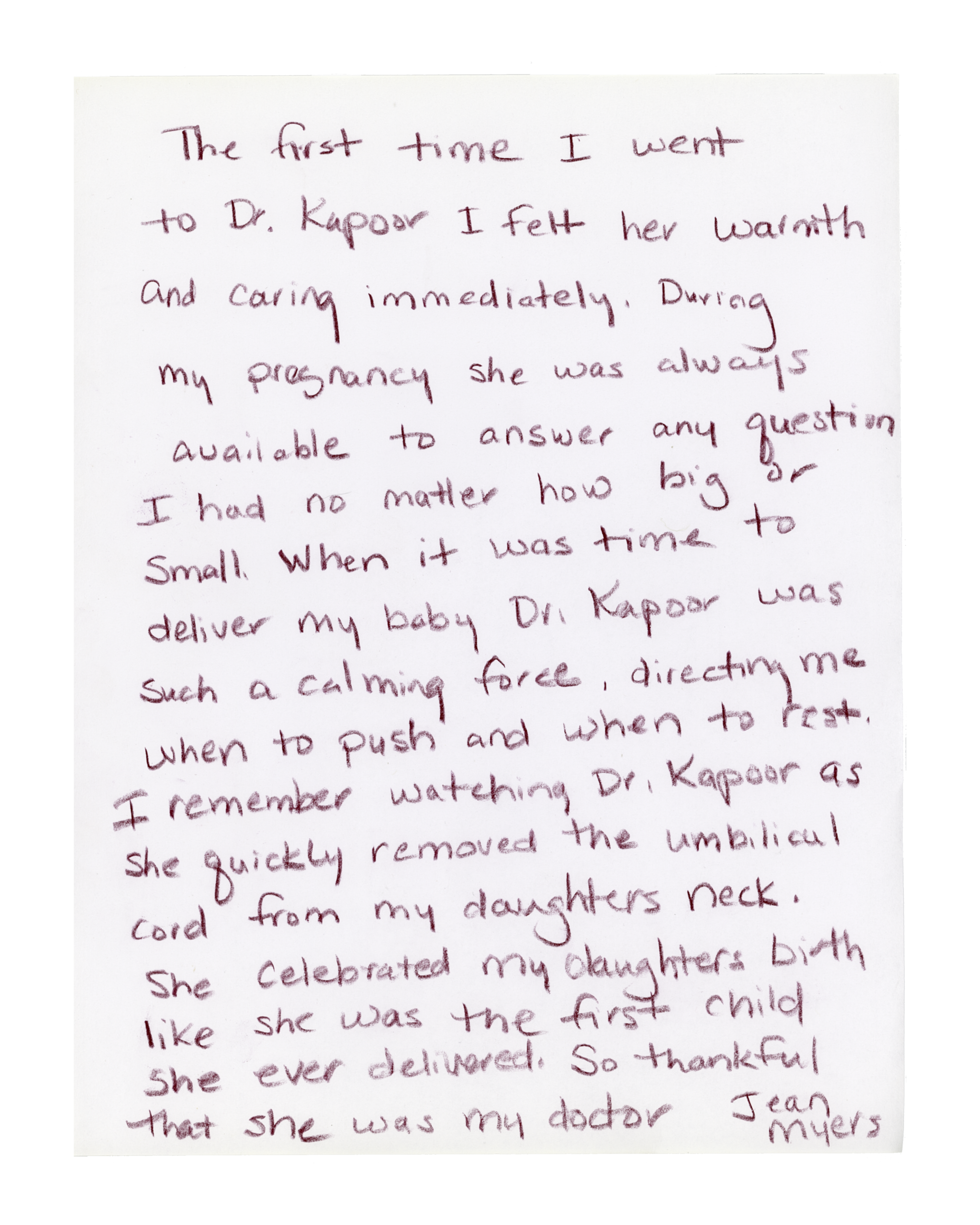

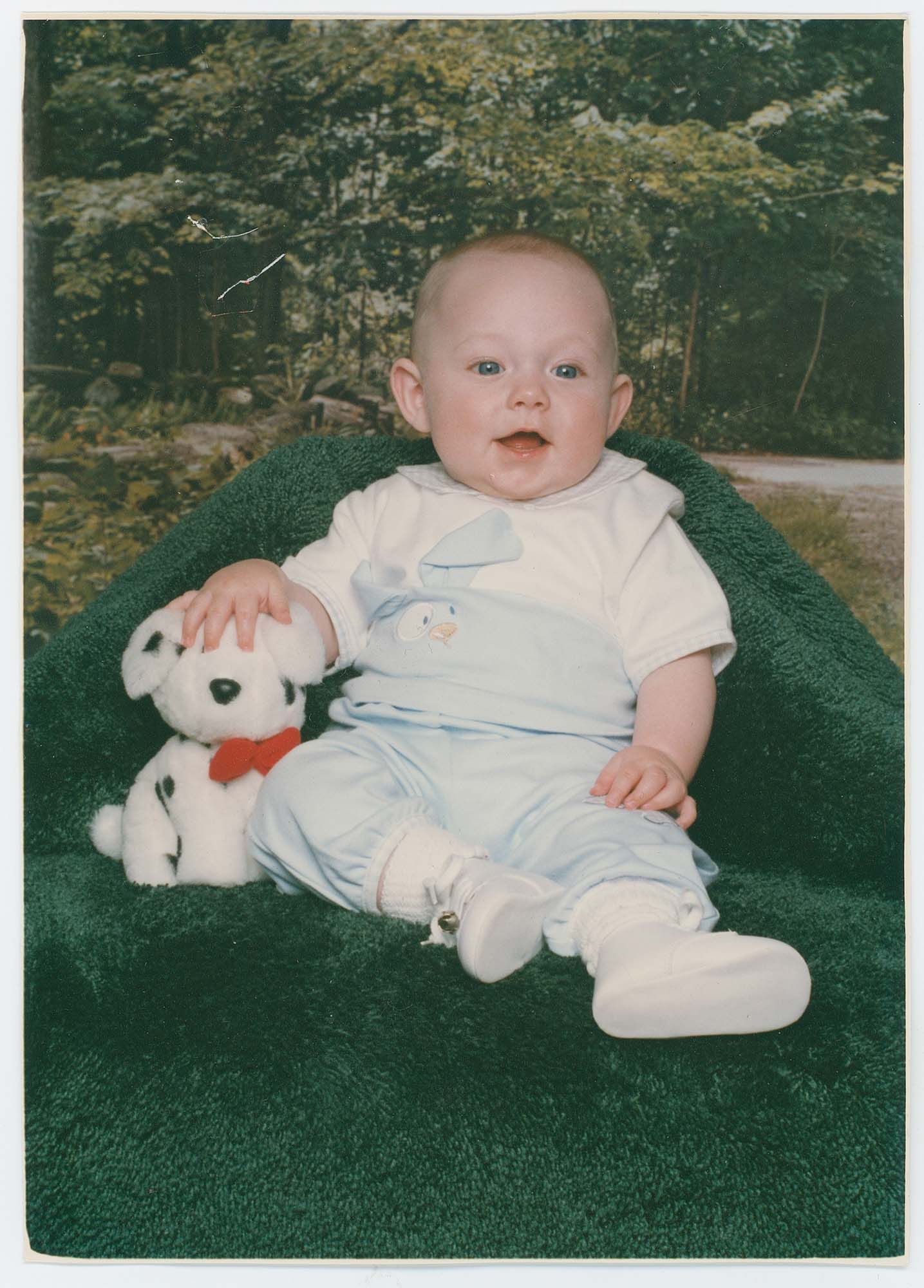

Indeed, every element of the multi-layered project embodies her. The portraits made in the parking lot echo the cork boards and albums filled with photographs that Kapoor remembers decorating Sarla’s office. “I knew I wanted to make portraits of individuals [she delivered],” he says. “When I was a kid, and I visited my mom’s office after school, there were all these cork boards in the waiting room and albums on the coffee table filled with photographs of kids.” Most of the original images were lost. Kapoor’s father recovered one small envelope from storage, and his mother asked around, with several people sending more. These feature in the series alongside Kapoor’s contemporary iterations created in the local library’s parking lot. For these, the artist contacted the local newspaper, asking for help tracking down individuals delivered by his mother. The publication ran a front-page feature — “that meant a lot to my mother. She began to cry when she read that”.

Indeed, every element of the multi-layered project embodies her. The portraits made in the parking lot echo the cork boards and albums filled with photographs that Kapoor remembers decorating Sarla’s office. “I knew I wanted to make portraits of individuals [she delivered],” he says. “When I was a kid, and I visited my mom’s office after school, there were all these cork boards in the waiting room and albums on the coffee table filled with photographs of kids.” Most of the original images were lost. Kapoor’s father recovered one small envelope from storage, and his mother asked around, with several people sending more. These feature in the series alongside Kapoor’s contemporary iterations created in the local library’s parking lot. For these, the artist contacted the local newspaper, asking for help tracking down individuals delivered by his mother. The publication ran a front-page feature — “that meant a lot to my mother. She began to cry when she read that”.

“My father gave her one of [the saris] when they first married. Another is a sari she wore when she officially became a doctor.”

– Vikesh Kapoor

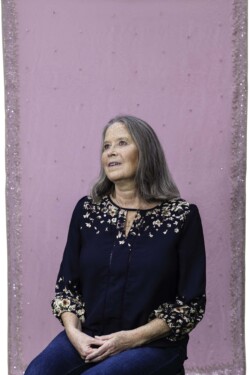

There is only one photograph of Kapoor’s mother in the series. She is elegantly dressed — a patterned scarf slung gracefully around her neck. She gazes pensively into the distance. “I wanted there to be one portrait of my mother and treat that differently,” he says. However, she is present too, if subtly, in every one of Kapoor’s new images: her saris providing the backdrops for each portrait; flashes of colour amid the parking lot’s drab exterior. “I would tell [my subjects] I brought a bunch of my mum’s saris and ask them to choose some that spoke to them,” says Kapoor. “Then I would narrow it down based on the aesthetics of what they were wearing and how they looked in photographs from their childhood.” The saris are not only aesthetic. They symbolise Kapoor’s mother’s roots too. “Even though she integrated herself into the community and wore American clothes when she worked, she came from India,” continues Kapoor. The saris are a reminder of that, and each one is symbolic of a moment in her history. “My father gave her one of them when they first married,” continues Kapoor. “Another is a sari she wore when she officially became a doctor.”

The work is not political. However, it is impossible not to consider it in the context of a post-Trump America where anti-immigrant sentiment ballooned. Indeed, when viewed through this lens, the series is a reminder that the US is ultimately a nation of immigrants — individuals like Kapoor’s parents who, in myriad ways, have devoted, and continue to devote, themselves to building the country.

For more information visit Leica

Find out more about the kit:

Leica SL2

APO-Summicron-SL 75 f/2 ASPH

APO-Summicron-SL 1:2/28 ASPH

NOCTILUX 50

Explore the full project here:

The post A story of devotion in a rural Pennsylvanian town appeared first on 1854 Photography.