His new 756-page story book explores the home life in a remote Japanese village that may soon be gone

In 1992, Swedish photographer Anders Edström travelled to the remote Japanese village of Shiotani for the first time. Just under 30 miles outside Kyoto, the village is home to only 47 inhabitants. Unbeknownst to him then, Edström would return to Shiotani multiple times over the coming years, as it is where the photographer’s then-girlfriend, and now wife, grew up. Since that initial visit almost three decades ago, Edström has taken countless photographs of his companions, his family, and the town’s landscape – saturated in the atmospheric hum of everyday life.

“One of the visitors said, ’I can’t believe your husband let you do that.’ That’s when I had the realisation that this is actually a piece of work. Because that person straightaway is making an assumption of how I should behave as an archetypal wife. And I thought, the piece of work goes beyond just me and my story.”

When Edström first arrived in the village, he had been taking pictures for seven years – his camera was an integral tool for relating to the world around him. “It was my way of being,” he explains. “The first time I went to Shiotani, I just wanted to have memories of the trip. I don’t think that the pictures I take when I visit any place for the first time are particularly interesting. I might get lucky – but when I see things for the first time, I don’t really know what to photograph, because everything new looks interesting. I haven’t developed a special point of view yet.” Edström photographed as a means of constructing an internal map and gaining an understanding of his surroundings, collecting the visual cues around him like a magpie, only to rifle through his frames on completion. He composed references to sights, people, and smells that would later lay the foundation for an exquisite long-term project: Shiotani, a 756-page chronicle published by AKPE.

Edström’s personal journey into familiarity with this remote place is what makes Shiotani so compelling. Indeed, the work is a documentation of remote living, but it’s also a historical record of Edström’s relationship to making photographic records, not only tracking his changes as an image-maker, but his throughlines, too. “When I first started taking pictures, in 1986, I used a Nikon F. A couple of years later, while working as an assistant for commercial photographers, I used all kinds of cameras, including old ones I found at flea markets. I wanted to learn everything, looking for different effects,” he explains.

“But throughout 1991 and 1992, I felt like I had reached a dead end,” he continues. “I wasn’t excited about experimentation anymore. I felt stuck. The weird colours and contrasts bored me, and when I looked back through all my rolls, I actually felt drawn to the first images I made back in 1986. They were so plain, catching the light of ordinary things around me, photographed in a straightforward manner. It felt detached, which was far more interesting than all those years of effort spent trying to make pictures look interesting. I wanted to see if I could go back to that original way of seeing and doing, just by being myself.” He decided to go back to his Nikon, “and it felt so neutral – nothing too poetic. The pictures in Shiotani were made with the same approach I had when I first started photographing seven years before.”

In 2006, over a decade after his first visit, his wife’s obaachan – Edström’s grandmother-in-law – asked to see the pictures she had watched him taking over the years. Noting her interest, for Christmas two years later, he gifted her a photo album of selections. The creative process of making the personal memento shifted the photographer’s understanding of his mass documentation. Rather than keeping an unseen archive of forgotten memories, Edström realised he could share this place with others in the form of a book.

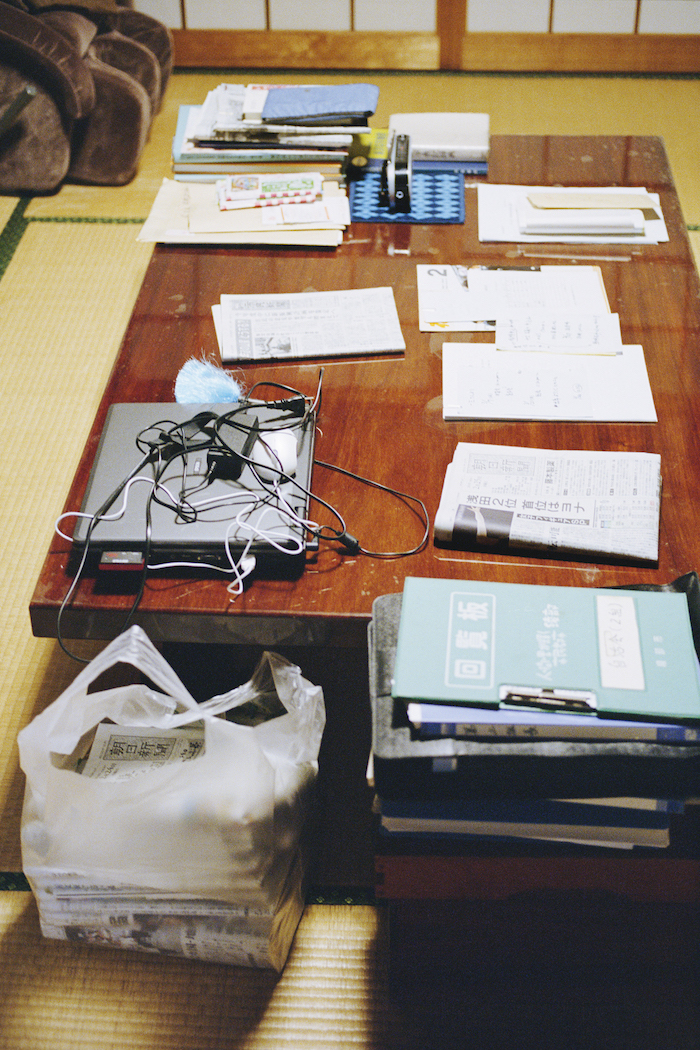

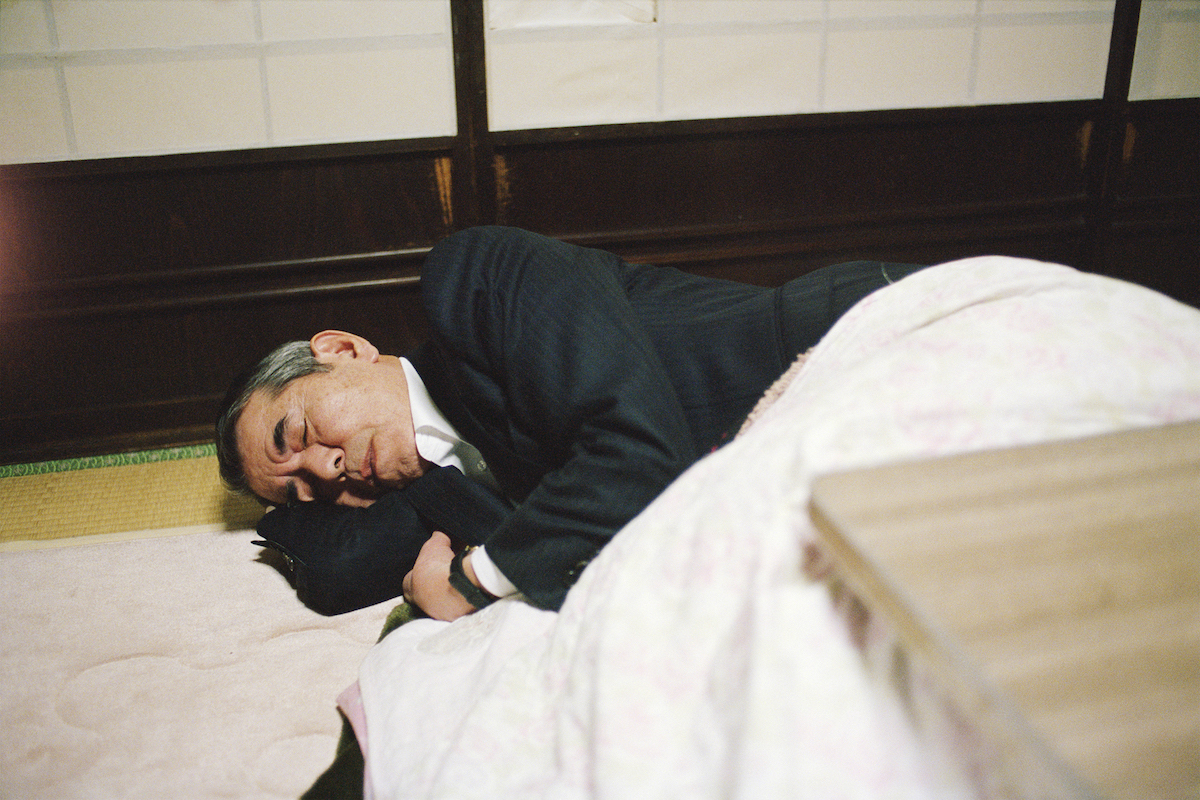

In the pages of Shiotani – full of silhouettes on paper doorways, the warm routine of family meals, or imperfect objects that caught Edström’s eye – we see how the photographer’s authorship, while seemingly nonchalant, is intentional. As the years pass, he becomes increasingly comfortable and familiar in his body. While Edström might not be visible in the photographs, we feel his presence – not necessarily as a documentarian, but as someone consistently rediscovering a place that is important to him. Edström’s return to simplicity in image-making is also reflected in the book’s design. The beige cover and straightforward typography reflect the mundane beauty of the photographer’s style.

“I have always liked beige,” he says. “I wanted the book to be plain and simple, and I also didn’t want to give away what happens on the inside. I wanted it to do the job of letting the reader go through the pages with as few distractions as possible.”

At 756 pages, Shiotani is expansive in comparison to most photobooks. It takes the viewer on a visual stream-of-consciousness that might suddenly feel slow and lethargic, only to rev up to rapid speed with the turn of a page. The book, which features images taken between 1993 and 2015, feels like a narrative from Edström’s dreamworld – a supercut of the process of familiarisation.

“One of the things I like most about making books is playing with time,” he explains. “I’m not interested in simply showing a collection of nice pictures. I want the sequence to give you some kind of feeling. It’s a bit like listening to a record: you might not like all the songs, but even the songs that you don’t like are important for experiencing the whole project.”

While there is a subjectivity in Edström’s photographs, imbued with personal sentiments of love and loss, the life and death of important family members, many of his themes contain universal sentiments. As time has passed and Shiotani evolves before his eyes, Edström feels that sharing this place with others is essential.

“This work is personal, but my work is always personal, even when I’m photographing pools of paint,” he reflects. “Photography is personal because we show each other the things that we find interesting to look at, presenting them in ways that reflect those feelings. Aside from thinking about what I like about the images, I can only hope that others find this work interesting, too.”

Through the mesmerising simplicity of Shiotani, Edström demonstrates that, for him, home is a collaborative interaction with his camera. Even though his mass of images started as a snapshot exploration – a way of making new surroundings feel increasingly familiar with the passage of time – the work is additionally about a place deserving of complex remembrance.

“This project is also about a dying village,” Edström reflects. “It is a document of a place that won’t exist forever. Nothing ever does, and that’s why it’s interesting to photograph things in the first place: to see what the world used to look like, or to see a village from the inside. It is ordinary and extraordinary at the same time. Shiotani is about time, life and death – and I just happened to be there to photograph it.”

Shiotani is published by AKPE and is available via Antenne Books

The post Anders Edström chronicles the nuances of daily life, love and loss appeared first on 1854 Photography.