This article is the first in a mini-series, In Search of Ourselves. We speak to three artists – Ana Vallejo, Bowei Young and Andre Ramos-Woodard – about vulnerability and trauma, and how they use the camera to gain a better understanding of themselves.

Young’s latest project attempts to illustrate the pain of homophobia, and the anxiety of existing in a society where fundamental human rights are in constant jeopardy

It has never been easy to be queer in China. Prior to the decriminalisation of homosexuality in 1997, the punishment for being in a same-sex relationship ranged from imprisonment to execution. While same-sex marriage is still illegal, a broader sense of acceptance is slowly emerging.

Bowei Young has been grappling with his sexuality since he was a child. Growing up in Hangzhou in a traditional Christian family, Young’s parents labelled queerness as a sin and forced him to undergo psychological treatment at 15. The consequences of this trauma and the ways it shapes one’s identity are a primary focus in Young’s practice. “To construct my work, it’s more like constructing a shelter,” he says. “Diving into the very personal psychic world is dangerous, yet being vulnerable requires great courage.”

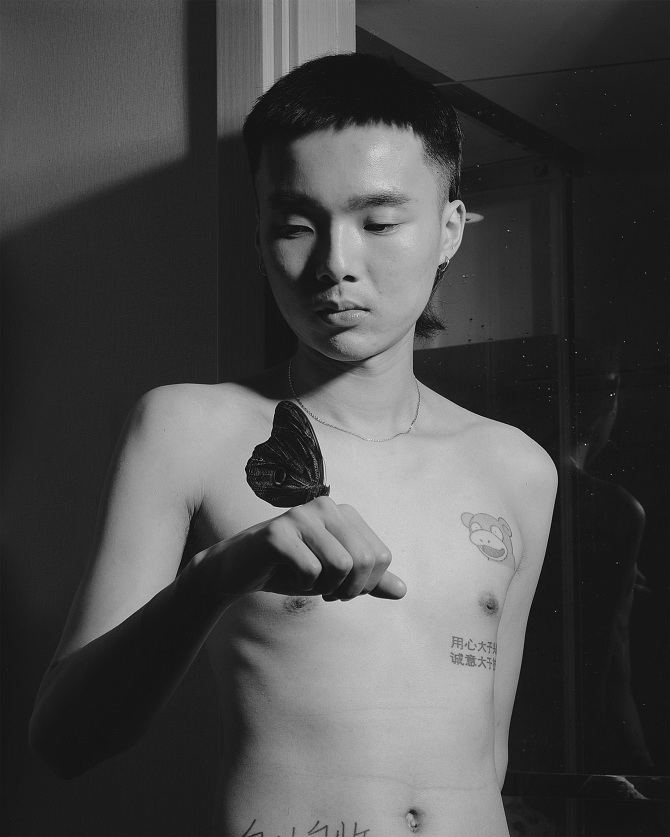

In Young’s latest project, If Spring Could Feel Ache, portraits of young queer Chinese men are punctuated by vivid red and amber burns, created in the darkroom. The marks emanate heat, summoning a bruise or wound. They linger like the repercussions of trauma, starting small, slowly consuming the entire frame. The project attempts to visualise the pain of homophobia; the anxiety of existing in a society where fundamental human rights are in constant jeopardy.

Young’s images address the dichotomies of care and conflict. Through the collision of childhood memories and portraits of his community created in China and the UK, the photographer collapses time and space, revealing the long-term consequences of trauma and how it manifests in the body and mind. Young’s work is as much a tool of healing as it is an artistic practice – in visualising isolation, shame and discomfort, he creates a visual release, offering a collective catharsis for his collaborators and the viewer.

Young’s work is made with, and for, his community. In honouring their experiences, he acknowledges the way life is given meaning through suffering and how we live through it. He animates his love and gratitude via poetic images that contain as much beauty as they do pain. Quiet, vivid and lyrical, his distinctly tender approach reminds us of the power of social healing and the freedom that emerges after coaxing trauma into the light. Within these frames, we witness Young harnessing the fear that once restrained him as fuel to craft a richer vocabulary around queer identity.

In Bessel van der Kolk’s book, The Body Keeps the Score, the writer and psychologist explains: “Being able to feel safe with other people is probably the single most important aspect of mental health.” While the queer community worldwide occupies a time as thick with possibility as it is uncertainty, work like Young’s validates the struggle while cherishing the importance of cultivating community in our quest for belonging.

The post Bowei Young visualises the experience of being young and queer in China appeared first on 1854 Photography.