This article is printed in the latest issue of British Journal of Photography magazine, Activism & Protest, delivered direct to you with an 1854 Subscription.

Safar Journal highlights arts and culture stories from across the Middle East and North Africa region. Here, the editorial team reflect on their recent projects, ethos, and photo selection process

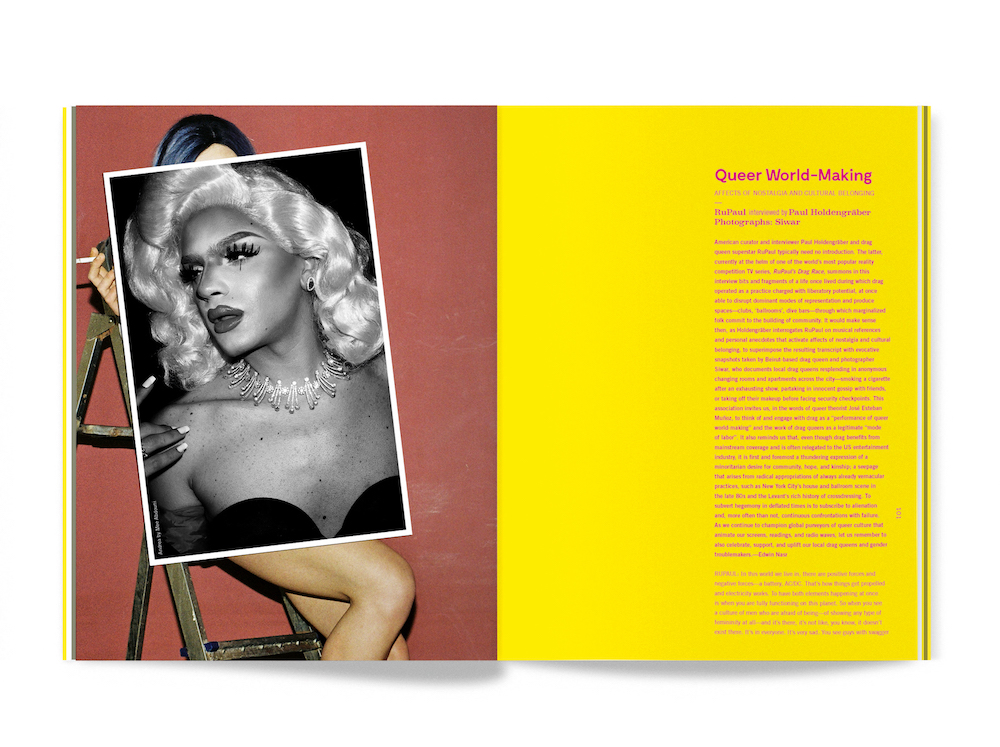

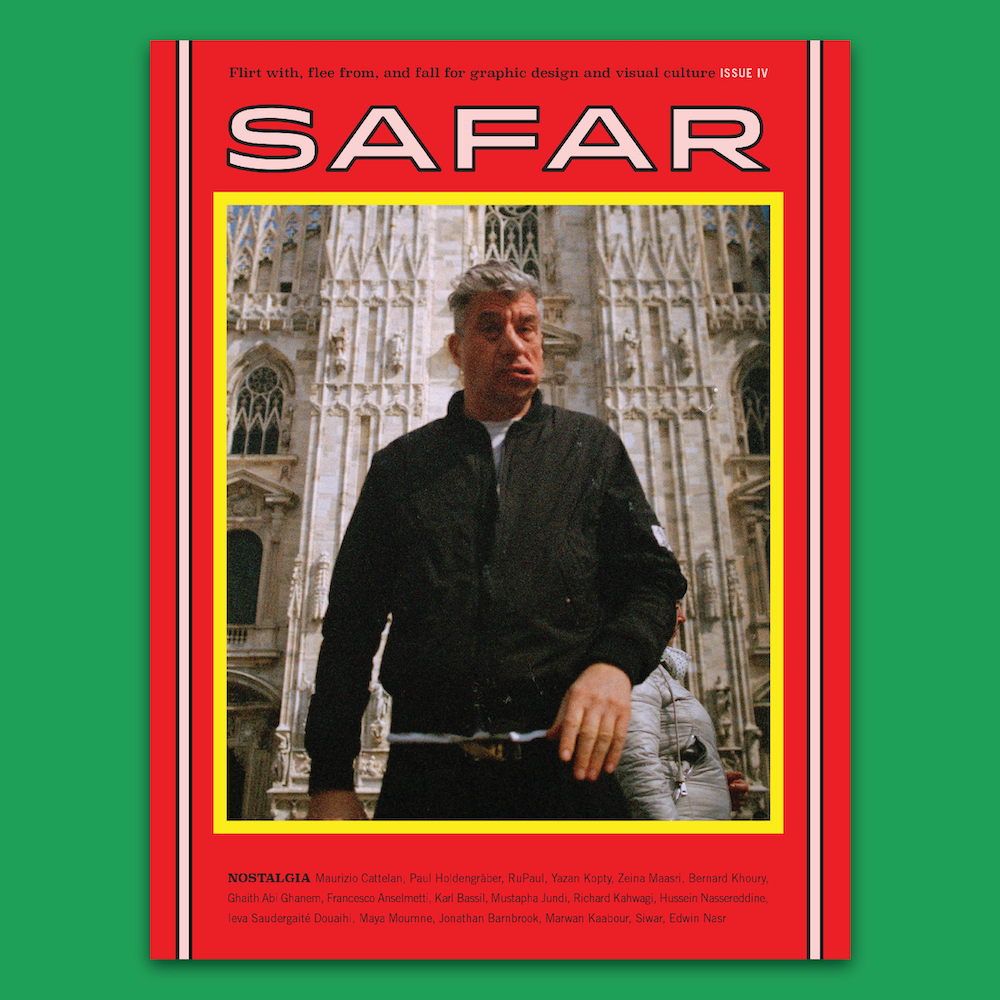

Safar is the Arabic word for travel. It also refers to communication, especially that seen across cultural and linguistic borders. Based in Beirut, Lebanon, Safar is a biannual and bilingual independent magazine that asserts the significance of graphic design in the production of culture.

Safar grew out of Studio Safar, a design and art direction agency led by creative directors Maya Moumne and Hatem Imam. The duo now act as the magazine’s editors-in-chief. By launching their own publication, the studio hopes to shift artistic conversations away from the Global North, focusing instead on the visual cultures found in the Middle Eastern and North African region. Here, they reflect on their production process.

British Journal of Photography: What do you look for when commissioning photographers?

Safar Journal: We seek out photographers who have a different way of seeing things; those who are shifting the focus, or looking to tell a story in a new way. The Lebanon creative community is well-connected, and we have met many of the photographers we work with through this. We also get emails in which people share their photography, design and illustration work, and we always take a look at those to see what might work for an upcoming issue.

BJP: Are there any features that stand out for you?

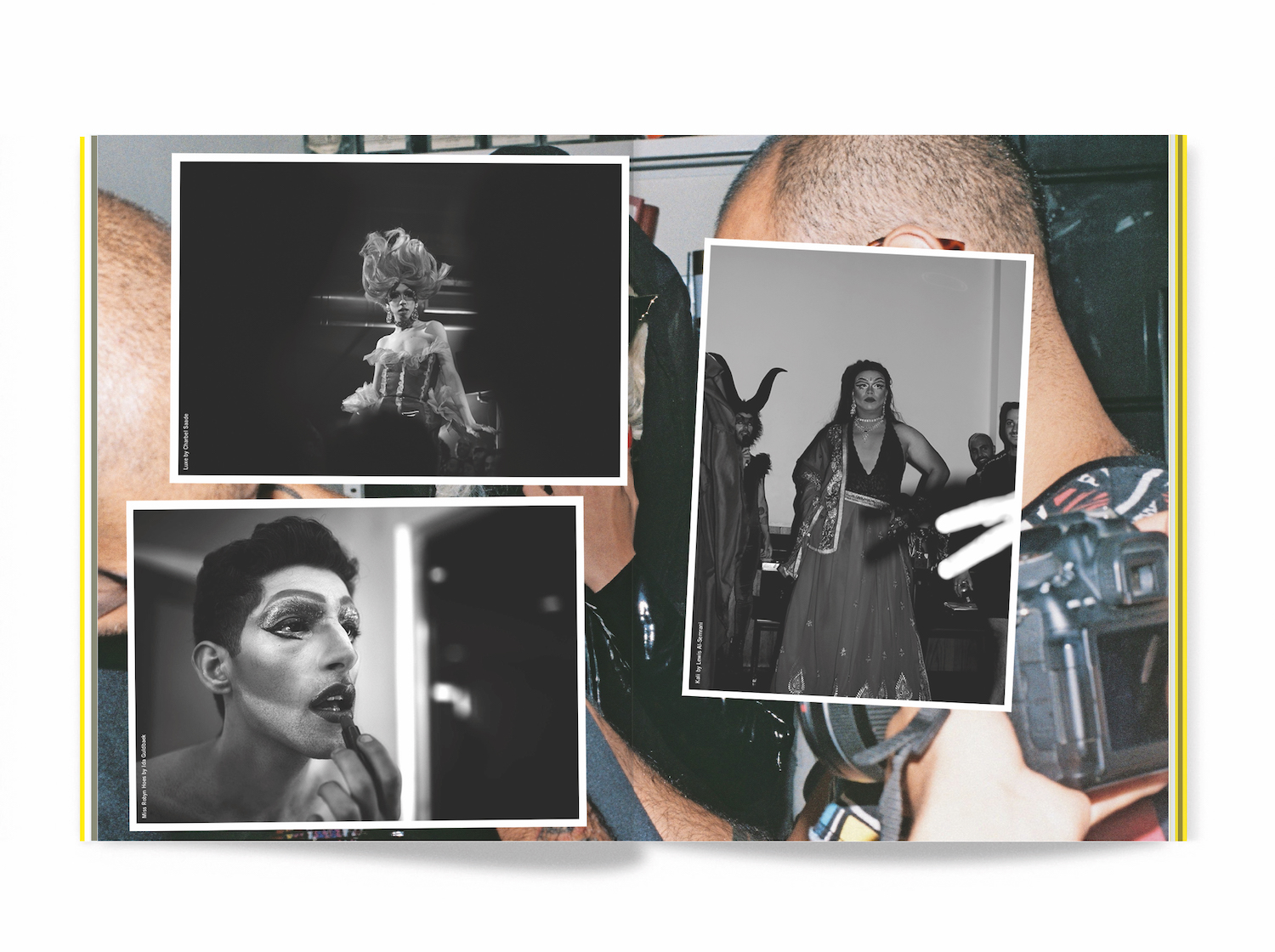

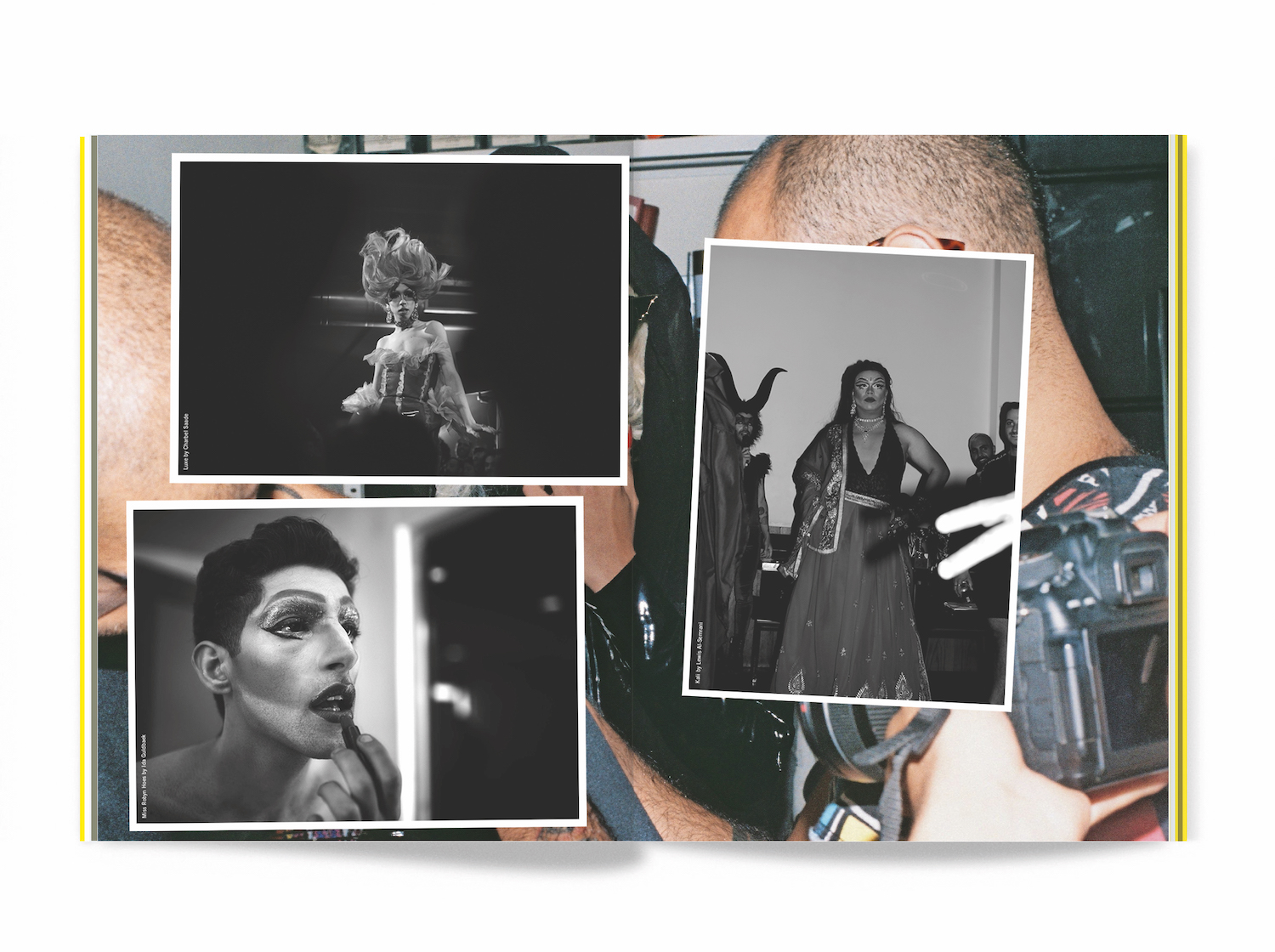

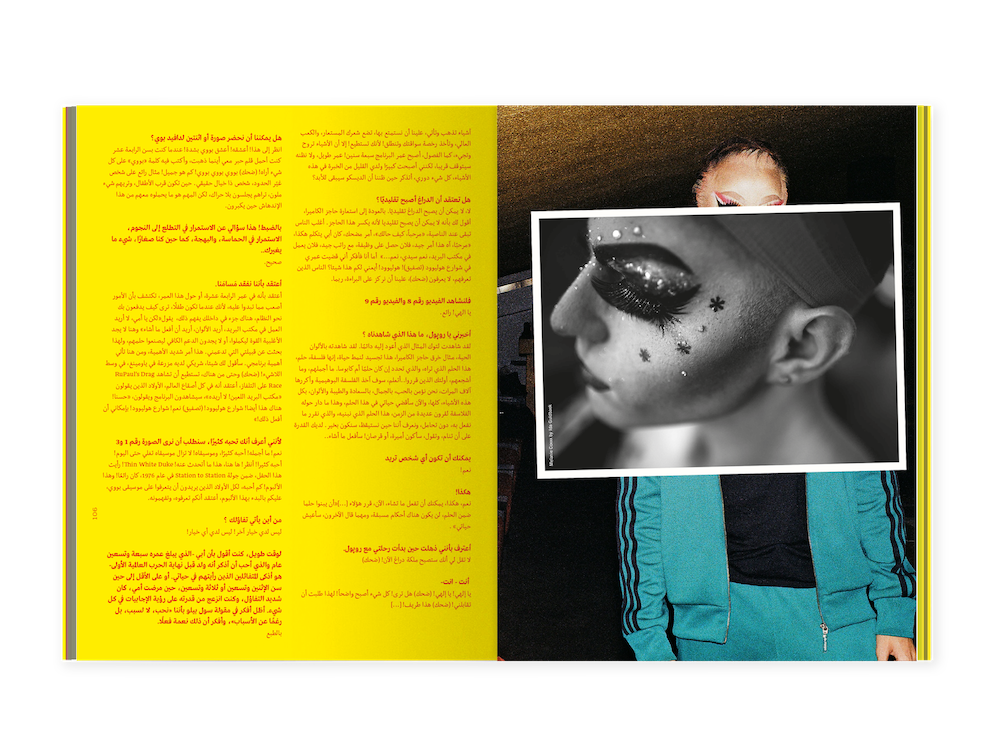

Safar: We selected some images to accompany an interview between the drag queen RuPaul and the American curator Paul Holdengräber, in which they talk about the significance of drag as an art form. The world of RuPaul is often presented as one in which drag is centred in America and the west, so we found a local photographer who had captured the drag scene in Beirut. We really wanted this photo series to accompany the interview and to serve as a gentle reminder that drag exists globally, even when unsafe.

BJP: Ultimately, some of the images were ‘censored’. Why did you take this decision?

Safar: A few of the drag artists featured in the photographs were at our issue launch event, and when they saw the photos, they told us that they were anxious about consent. We worked together with them to find a solution. This was especially urgent given that some of the artists were concerned about tattoos, jewellery and other personal markers that appeared in the photos and could give away personal details and, in some cases, put them in danger. We knew immediately that we had to censor them. We would never want to upset, hurt, or endanger any individual by publishing our magazine, nor would we want to cause any form of harm to the LGBTQIA+ community in Beirut. We initially considered reprinting, but felt that this would be a wasteful solution.

BJP: How did you overcome this issue?

Safar: We agreed with all of the featured drag artists that they would select and share photos that they found more comfortable. Our team hand-stuck the images into the magazine to cover up the old photographs. Though not at all what we had originally anticipated for this article, the outcome speaks powerfully to the importance of consent in photography, publishing and representation more broadly. It came to life when they were in control of how they appeared. Ultimately, this made the piece infinitely better.

BJP: What advice would you give to emerging photographers?

Safar: Look where others aren’t looking. Some of our favourite photo series have featured communities that are often not given a lot of attention, especially in mediums like photography and print. Be respectful and incredibly mindful of what images you take, and how you share them.

The post Creative Brief: Safar Journal appeared first on 1854 Photography.