This article is printed in the latest issue of British Journal of Photography magazine, Activism & Protest, delivered direct to you with an 1854 Subscription.

When the catastrophic blaze tore through the seaside region of Attica, the young mother instinctively began to document the experience, which she now self-published in a photobook

Before you see a wildfire, you hear it, says Katerina Angelopoulou. “No one can tell you unless they have been in one,” the Greek photographer explains. “It is a sound that can haunt you. What overwhelms you is the force.”

On 23 July 2018, in Mati, a seaside satellite town 30 kilometres east of Athens in the region of Attica, the deadliest wildfire in Greek history took hold. Since childhood, Angelopoulou has spent summers in the region, where her parents still live – “and ultimately the only place I could identify as home in my ever-transient existence,” she says.

At the time, she was living in New York City and had arrived in Greece two days earlier with her daughter. She remembers playing with her three-year-old and reconnecting with her ageing parents in the quiet peace of the town before hearing the fire charge towards them over the brow of the surrounding hills. “The fire rushed from the hilltops, jumping over the pine trees, and to the edge of the sea in less than an hour and a half,” says Angelopoulou. Temperatures rose quickly and strong wind gusts of up to 124km/hour moved the fire remorselessly forward. “It swallowed everything in its passage.”

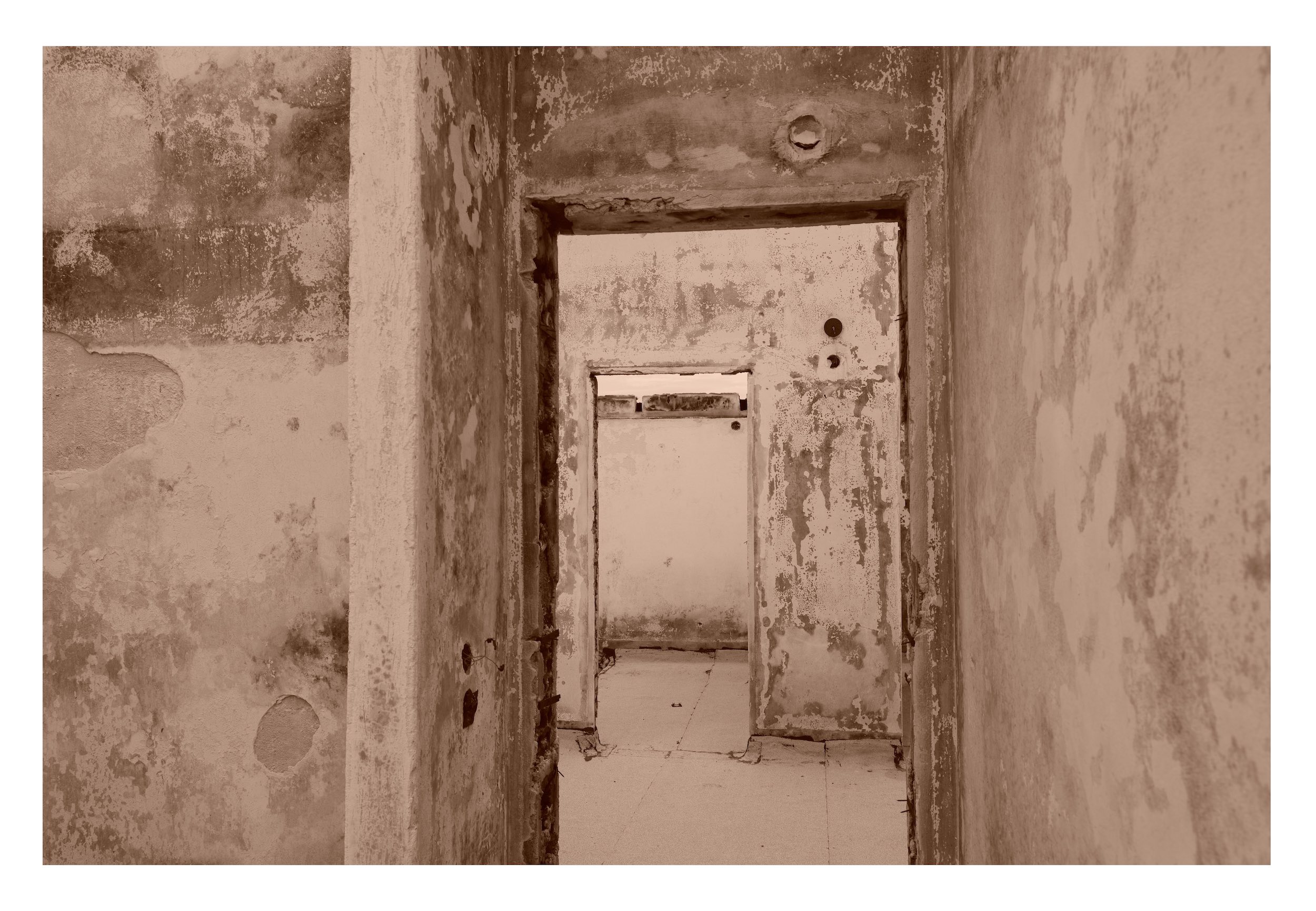

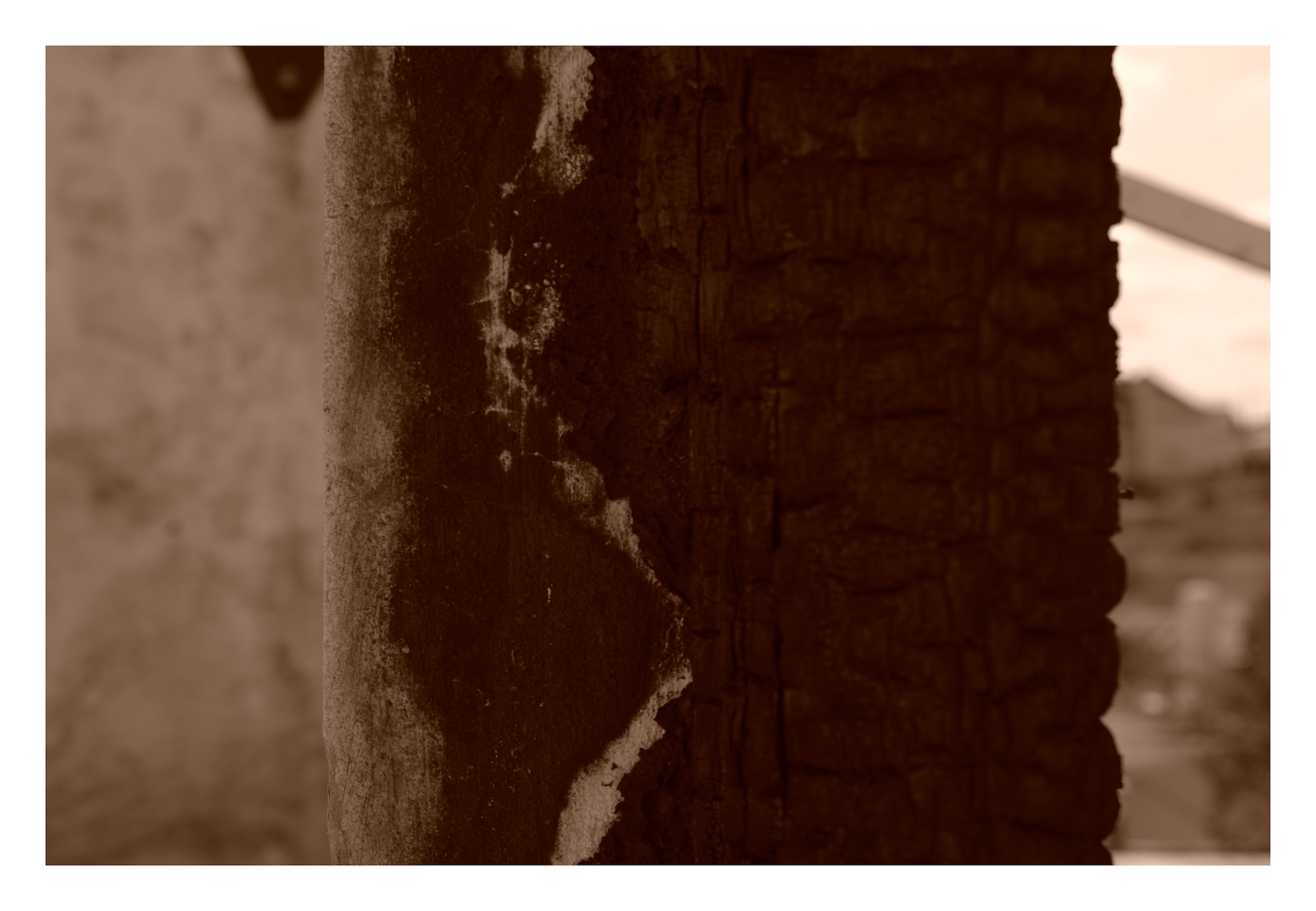

Angelopoulou reflects on the personal and shared trauma of being suddenly caught in such a Dante-esque nightmare in her project The Sound of the Seen. She has self-published the work as a book after completing her MA in documentary photography from London College of Communication in June. The book also reflects on photography’s ability to act as evidence, reconstructing in forensic detail how the citizens of Attica were failed by the Greek state in its response to the fire, which killed 103 people and destroyed over 4000 homes. The publication comprises a combination of snatched mobile shots Angelopoulou took instinctively as the wildfire approached, as well as images she made when returning to Attica after the fire had finally burnt itself out, capturing the gutted homes, withered trees and charred devastation that remained.

Angelopoulou has written powerfully about her experiences of protecting her family during the fire, some of these memories appearing in the photobook. “There is thick black smog, the crackling of trees going up in flames and the sound of things blowing up,” she writes. “‘We should swim,’ says my mother. The only thought that keeps circling in my head is, who – my mother, who is using a walking stick and can’t breathe, or my three-year-old – will I have to let drown first? Who do I choose to give up on first? I am not leaving her again. I just say, ’No – we are not going to swim’.”

The final chapter is focused on the failings of the Greek fire department, which did not adequately respond to the disaster and its immediate aftermath. “People were abandoned,” she writes. It includes disjointed textual accounts of the fire, written by Angelopoulou herself and other survivors, which are intertwined with data and descriptions of the blaze from the State Investigation Report. These were eventually compiled to take the Greek fire service to court for dereliction of duty.

The book is designed to “bear witness to one’s own experience,” says Angelopoulou. “The collective experience; the collapse of the state’s mechanisms, and the universal experience of climate disasters.”

The post Katerina Angelopoulou’s harrowing account of Greece’s deadliest fire appeared first on 1854 Photography.