Geoushy’s response to Malala Fund’s Against All Odds commission, in collaboration with 1854, follows the lives of Rooka, a footballer, and Malak, a gymnast. The resulting project spotlights the young women’s resilience in the face of deep-rooted social stigma and lack of sponsorship and funding

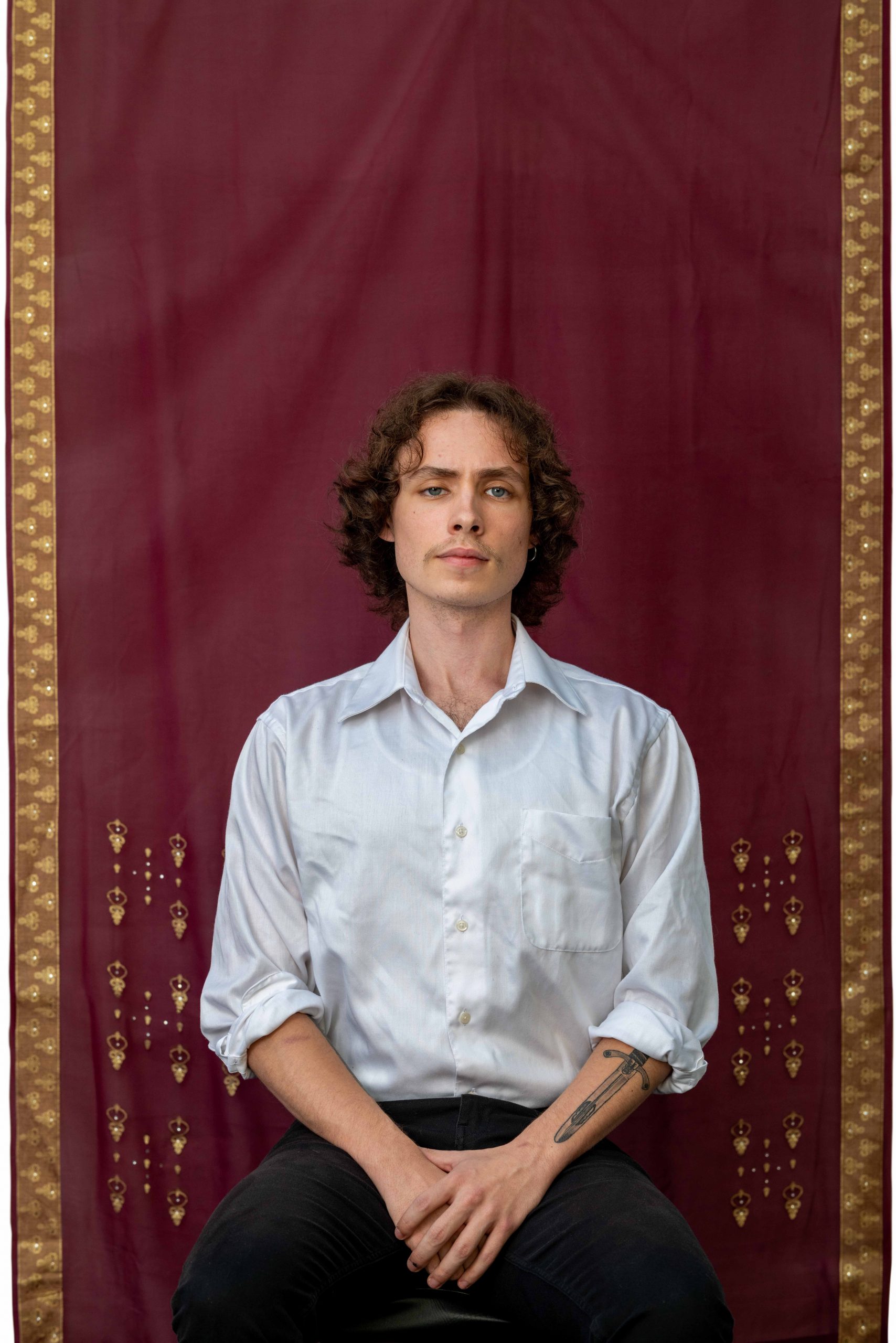

The inky silhouette of 20-year-old Rooka sits razor sharp against a fading Cairo sun: her arms outstretched, her face to the sky, a football skillfully balanced between her nose and forehead. Through Lina Geoushy’s lens, Rooka is breaking free.

As in many parts of the world, Egypt’s football industry is not a welcoming space for women. Support from the Egyptian Football Association is in short supply, and media interest for their matches almost nonexistent. When an Egyptian network did broadcast a Women’s U20 National Football Team match in December 2020, it triggered a torrent of misogynistic abuse from men online. The conservative leaning of Egyptian society also means many parents are reluctant to allow girls to pursue the sport in the first place.

Nonetheless, Rooka was a dedicated player for Egypt’s Junior National Team, and one of two subjects that take centre stage in Geoushy’s response to the Against All Odds commission from Malala Fund and 1854. Titled Cleopatras Scoring Change, the series delicately documents the daily lives of Rooka and 20-year-old Olympic gymnast Malak: two Egyptian female athletes who represent strength and determination in the face of stigma and discrimination by the country’s discriminatory sporting culture.

“Malak and Rooka are breaking stereotypes that are ingrained in Egyptian culture”

-Lina Geoushy

Cairo-born Geoushy has little interest in fuelling false Western ideas that all Middle Eastern women are oppressed. Egyptian women are educated; they work, drive, go out, and enjoy many freedoms. But, “Malak and Rooka are breaking stereotypes that are ingrained in Egyptian culture,” she says, “where mixing with men and moving or exposing your body lessens your value as a woman”. Cleopatras Scoring Change is an ode to their resilience – and to sports, more widely, as a vital part of young people’s search for identity, community, and purpose.

Rooka grew up in one of Cairo’s impoverished neighbourhoods: a quarter of Manshiyat Naser. She was bullied by other children for her dark skin, but found solace in playing football as part of a local church group. It was there that she was first scouted by a coach for her impressive skills. But as she got older, her parents weren’t supportive of her pursuing the sport as a career.“They felt it was not feminine enough; that she was going to get injured, and that her skin would get even darker [from being outside too much].”

Rooka was not deterred. Through her adolescent years, she saved up money her father gave her for specific purposes – to buy lunch at school; to spend on private tutoring lessons – and used it to pay for public transport to get to football training. She would hide injuries she sustained while playing, enduring the pain in private out of fear her parents would ban her from the game if they knew.

In Geoushy’s images, Rooka is at once dreamy and determined: intimate moments in her bedroom, and gazing over her hometown, are weaved between portraits of her stretching and playing on the pitch. “I am hoping all my hard work and all the effort I put in comes to fruition,” Rooka says today. “And that I can prove to my family or anyone who demotivated me that it was all worth it.”

Malak, on the other hand, came to her sport of choice – gymnastics – aged nine. She always felt she had to push herself further to compensate for not having begun training earlier in life. In particular, she has come to struggle with mental blocks, brought on by the sheer pressure of the sport. “With gymnastics, one wrong move can end your career,” Geoushy explains, which fosters a destructive culture for athletes; one that Simone Biles bravely brought to light when she dropped out of the 2021 Olympics due to mental health struggles this year.

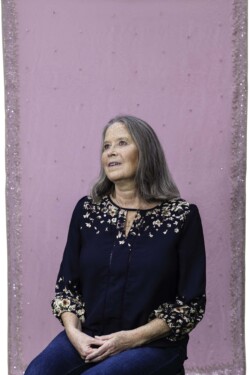

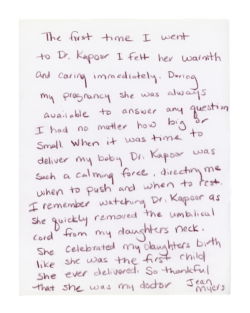

“My father gave her one of [the saris] when they first married. Another is a sari she wore when she officially became a doctor.”

– Vikesh Kapoor

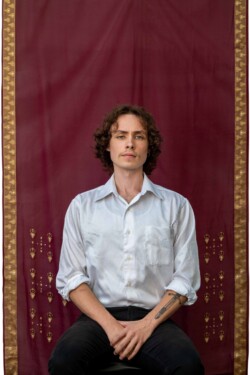

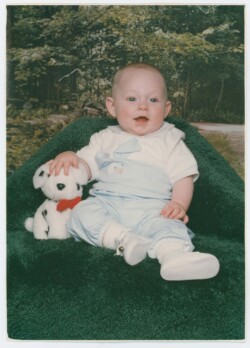

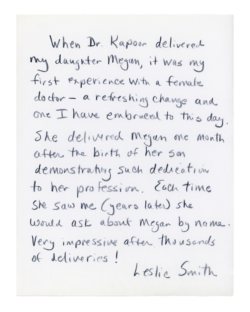

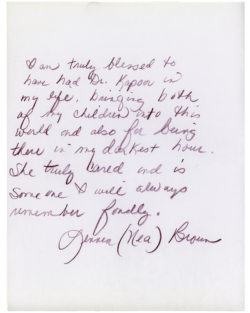

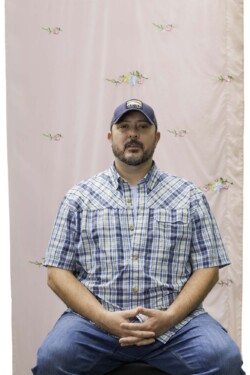

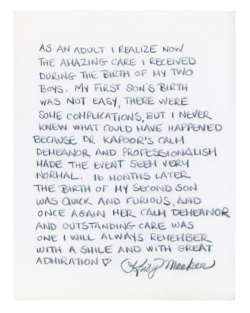

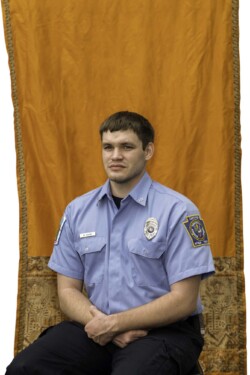

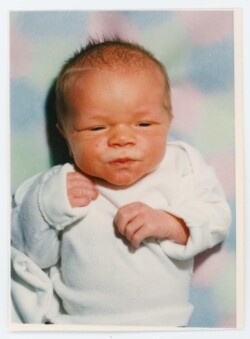

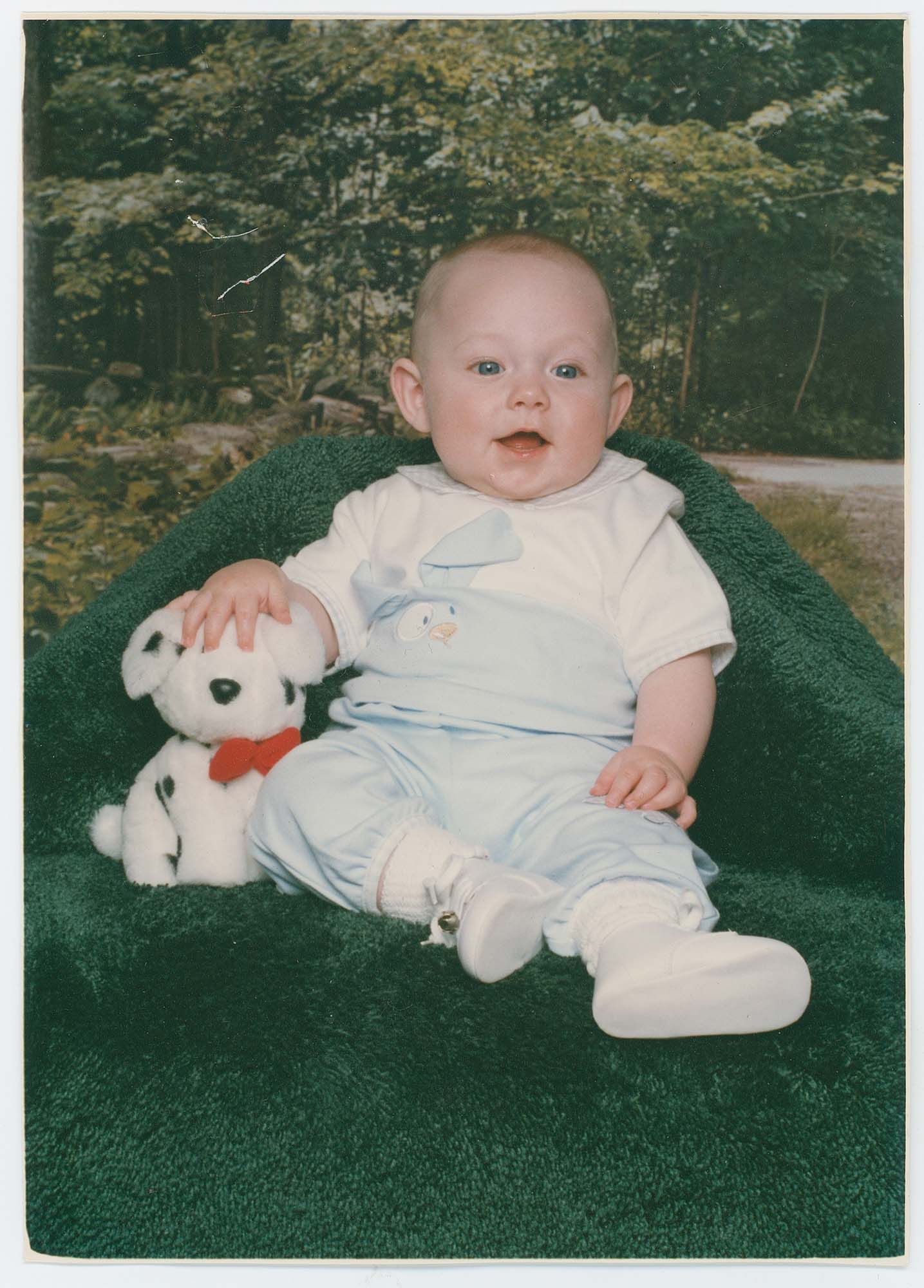

There is only one photograph of Kapoor’s mother in the series. She is elegantly dressed — a patterned scarf slung gracefully around her neck. She gazes pensively into the distance. “I wanted there to be one portrait of my mother and treat that differently,” he says. However, she is present too, if subtly, in every one of Kapoor’s new images: her saris providing the backdrops for each portrait; flashes of colour amid the parking lot’s drab exterior. “I would tell [my subjects] I brought a bunch of my mum’s saris and ask them to choose some that spoke to them,” says Kapoor. “Then I would narrow it down based on the aesthetics of what they were wearing and how they looked in photographs from their childhood.” The saris are not only aesthetic. They symbolise Kapoor’s mother’s roots too. “Even though she integrated herself into the community and wore American clothes when she worked, she came from India,” continues Kapoor. The saris are a reminder of that, and each one is symbolic of a moment in her history. “My father gave her one of them when they first married,” continues Kapoor. “Another is a sari she wore when she officially became a doctor.”

The work is not political. However, it is impossible not to consider it in the context of a post-Trump America where anti-immigrant sentiment ballooned. Indeed, when viewed through this lens, the series is a reminder that the US is ultimately a nation of immigrants — individuals like Kapoor’s parents who, in myriad ways, have devoted, and continue to devote, themselves to building the country.

For more information visit Leica

Find out more about the kit:

Leica SL2

APO-Summicron-SL 75 f/2 ASPH

APO-Summicron-SL 1:2/28 ASPH

NOCTILUX 50

Explore the full project here:

The post Lina Geoushy documents the female athletes pushing back against Egypt’s biased sporting culture appeared first on 1854 Photography.