A playful, illicit urgency under a harsh camera flash. Art on the cusp of creation and the artist on the cusp of being caught. Such was the life documentary photographer Martha Cooper chased as she captured the emerging graffiti scene in 1980s New York City.

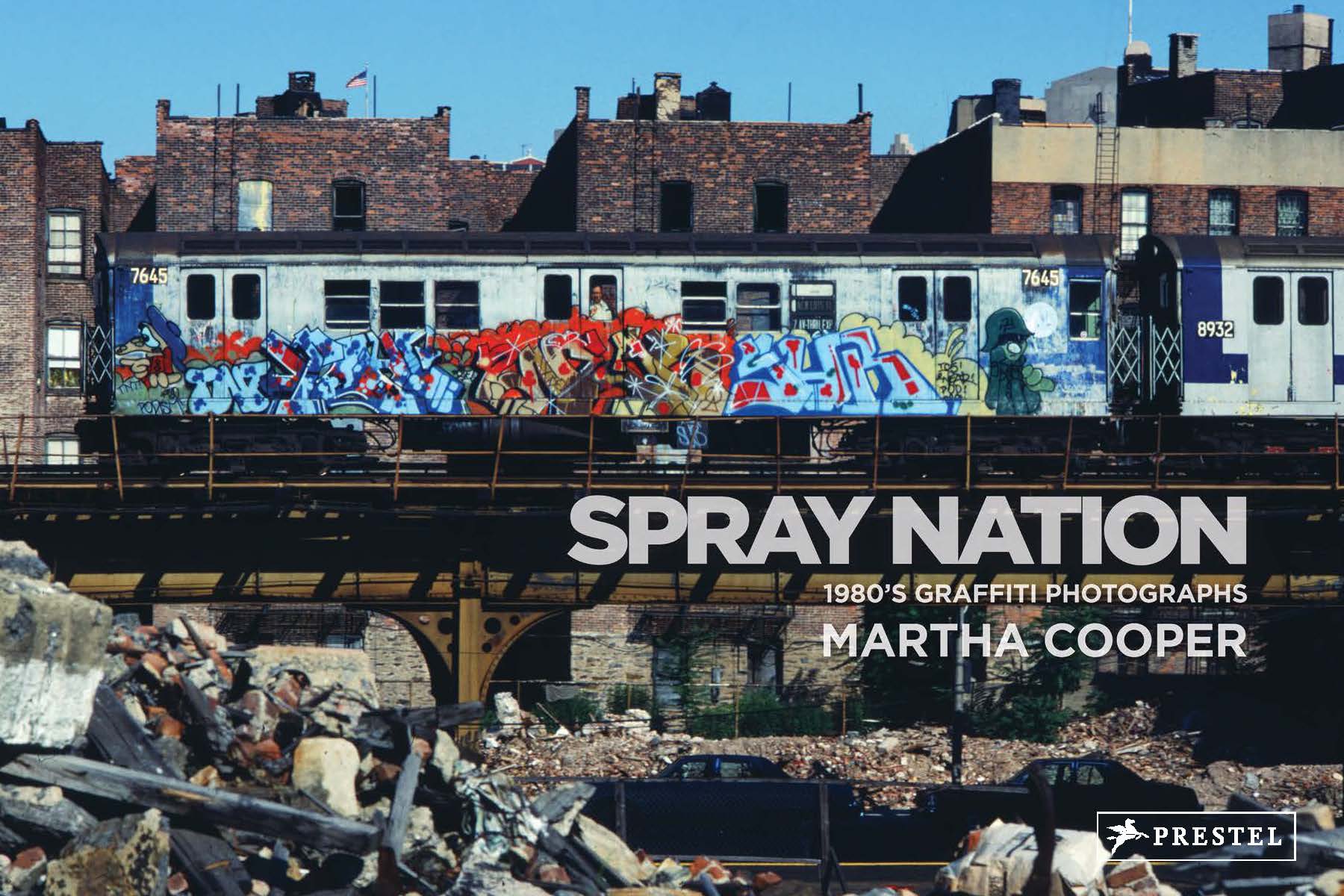

Now, nearly 40 years after the publication of her revered Subway Art, Cooper returns with a companion photo book, Spray Nation. Action, adventure, and artistic anarchy abound, it features the photographer’s previously unpublished work, including images of fellow creatives like Patti Astor, Fab 5 Freddy, Rammellzee, DONDI, and LADY PINK.

Even today, Cooper continues to travel the world documenting graffiti culture. When asked why, the answer is just as thrilling.

“I think the illegal aspect is exciting,” she writes to PopPhoto. “As soon as you go on any kind of illegal mission, you understand the thrill because it’s an adventure. It’s an art competition that takes a lot of skill to see who can get up the most with the best style. It takes a lot of planning to pull off a great piece at a great spot and that adds to the excitement.”

Related: Leica’s latest ‘drop’ may be the world’s trendiest camera

A photography trailblazer

Few were better suited to capture the birth of NYC‘s underground graffiti culture than Cooper, it turns out. A trailblazer in her field, Cooper claims the distinction as the first female intern at National Geographic and followed up as the first female staff photographer at the New York Post. At the Post, Cooper covered all sorts of news: crime, stakeouts, celebrity portraits, and more. Her “weather shots”—a feature photo thrown into the paper when space was available—are compiled in another book, New York State of Mind.

Then, in 1979, she met the graffiti artist HE3, who would be her connection to a formidable introduction with the artist Donald Joseph White, aka DONDI.

Meeting DONDI

As it turned out, DONDI was already familiar with Cooper the day she and HE3 rode up to his home in Brooklyn.

“When I introduced myself, DONDI said, ‘Oh, Martha Cooper!’ He knew because he had clipped a picture from the Post that I had taken of a kid on a rope swing with a Dondi piece on the wall with my credit line and pasted it in the front of his black book,” Cooper explains. “That was a perfect connection because graffiti writers wanted fame and I had given DONDI a lot of fame with that photo—although at the time, I was surprised to learn that the writer of the graffiti could be identified. That was a revelation.”

The meeting was followed by an invitation from graffiti writer Eric Deal to interview DONDI and his friends. Cooper recalls shooting indoors on Kodachrome 64 ISO. And that was the beginning of her foray into the underground art scene.

“DONDI was the first graffiti writer I met. He was respected and he vouched for me,” Cooper says. “DONDI introduced me to other writers at the Sam Esses studio in 1981. Relationships evolved from there.”

A subway car sparks a lifelong interest

Though her relationship with DONDI gave Cooper an “in,” the spark that really stoked her interest in graffiti occurred the day she took a hard look at the New York City subway. DONDI constantly referenced it, so Cooper decided to see what the hubbub was about.

“In 1980, I went up to 180th Street in the Bronx where the trains run above ground and started looking,” she recounts. “The first time I went, the LEE train with the poem on it was sitting there. It must have been freshly painted the night before. It was the very first day! I started going back. I had a car and I drove along the tracks looking for interesting backgrounds. The second day, a full BLADE car came by with most of the windows still painted. I shot a few of my best pictures those first few days and that really got me going.”

Dodging danger

A true journalist, Cooper didn’t settle for merely documenting the final product. She also tagged along as the graffiti artists snuck around train yards on early mornings, making their mark with the rising of the sun.

“To me, the story wasn’t complete until I could see how graffiti was painted,” Cooper shares. “Whenever I was with them it was usually, ‘Let’s get this done.’ It was a mission and they were professionals. They know how to get in, do their thing, and get out. I was definitely an outsider and tried to make myself invisible. I wasn’t a participant observer. I didn’t help carry the paint. I just tried to quietly be a fly on the wall. That was my approach.”

Capturing these clandestine scenes took quick thinking on multiple fronts. At the time, Cooper was shooting film on a Nikon FM. So, in addition to coming up with creative exposure techniques (a flash could draw attention) and angles, reloading the camera was also a factor—all while dodging the law.

“I was all about, ‘How am I going to capture this?’ What equipment do I need to carry while ducking under the fence and crawling in and out of the yards?” she elaborates. “I couldn’t put anything down. Sometimes a guard would come and I would have to duck under the car near the third rail and think, ‘I hope this train doesn’t move because I’m dead.’ I don’t have any stories of being chased out of the yards but I always knew it could happen and I had to be prepared to run with the camera gear.”

Graffiti culture today

Today, graffiti enjoys wider public acceptance. The medium has even found its way into the contemporary wings of museums and galleries. Back in the 1980s, however, there was a different story.

“In the early ‘80s, the scene was primarily New York City-based and very underground with few outsiders understanding what was going on,” Cooper remembers. “Today graffiti and the related (but different) street art scene is a huge worldwide art movement.”

Aside from museums, graffiti still remains very much a public, democratic form of art. And Cooper is gratified to see the mainstream audience’s enthusiasm for the medium, from community-painted trains in South Africa to public graffiti events in Tahiti.

On Spray Nation and Subway Art

Following on the heels of Subway Art, Spray Nation is a companion book and collaboration between Cooper and her editor, Roger Gastman. To compile the images, Gastman culled through thousands (perhaps hundreds of thousands) of slides, scanning them and planning the layout. When asked how the two tomes compare to the other, Gastman is adamant: Neither is trying to outdo the other.

“They were shot at the same time but are edited very differently for content,” he shares. “For Spray Nation, we labored over thousands of the images that had not been published to find the best of the best of the photos that told a story and were just great photos. Spray Nation is also a landscape format book that is much longer than Subway Art. We would never want to compete or compare to Subway Art—just be a companion.”

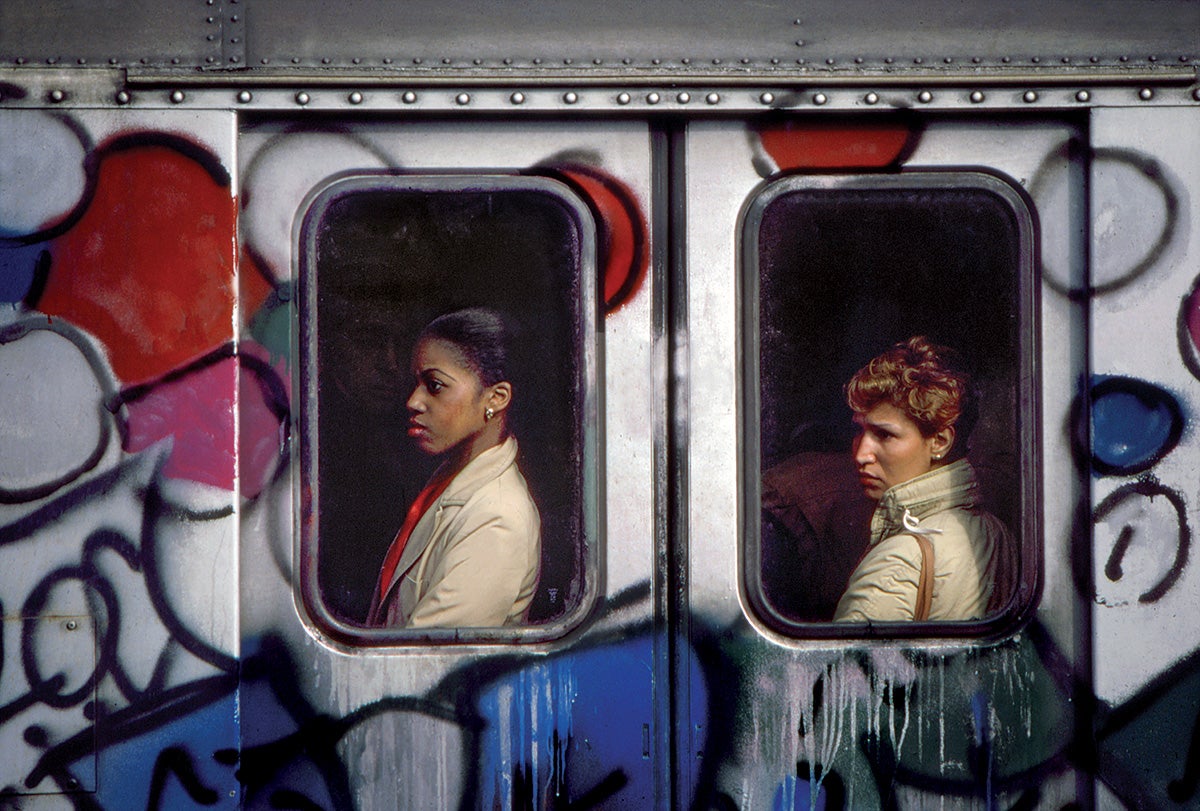

A touch of humanity, however, sets Spray Nation apart from its peers. It’s not so much about just the final works proclaiming themselves on screeching trains, it’s also about the people.

“It was important to group several artists and themes, such as sayings, characters, storefronts, and gallery works together,” Gastman finishes. “It was also important for me to make sure every so often there were people in the photos. That was easier than I thought it would be as Martha did such an amazing job always capturing the story and the scene—and not just the graffiti, as most did.”

The post Martha Cooper revisits the chaotic, gritty & enchanting world of graffiti in 1980s NYC appeared first on Popular Photography.