|

| Illustration courtesy of NASA |

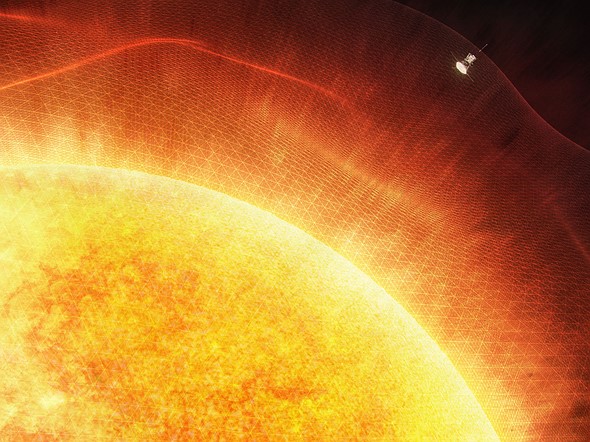

NASA has announced that the Parker Solar Probe has flown through the Sun’s upper atmosphere, the corona, for the first time. While there, the probe sampled particles and magnetic fields and captured historic, close-up photos of coronal streamers.

Much like humankind’s first steps on the Moon, the Parker Solar Probe’ touching the very stuff the Sun is made of’ will usher in a new era of solar science. We are significantly closer to understanding critical information about the Sun and how it influences the solar system and Earth itself.

‘Parker Solar Probe’ touching the Sun’ is a monumental moment for solar science and a truly remarkable feat,’ said Thomas Zurbuchen, the associate administrator for the Science Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters in Washington. ‘Not only does this milestone provide us with deeper insights into our Sun’s evolution and its impacts on our solar system, but everything we learn about our own star also teaches us more about stars in the rest of the universe.’

The Parker Solar Probe is making discoveries that other spacecraft couldn’t because they were too far away. The Parker Solar Probe observed the flow of particles within the solar wind and identified where they originate, the solar surface itself. Continued close flybys will offer additional data and insight on phenomena that cannot be observed from distance. ‘Flying so close to the Sun, Parker Solar Probe now senses conditions in the magnetically dominated layer of the solar atmosphere – the corona – that we never could before,’ said Nour Raouafi, the Parker project scientist at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland. ‘We see evidence of being in the corona in magnetic field data, solar wind data, and visually in images. We can actually see the spacecraft flying through coronal structures that can be observed during a total solar eclipse.’

After launching in 2018, the Parker Solar Probe has made other significant discoveries. The spacecraft crossed the Alfvén critical surface for the first time on April 28, 2021. Scientists had previously not known exactly where this critical surface is. It’s the point that marks the end of the solar atmosphere and the beginning of the solar wind. Beyond the Alfvén critical surface, solar wind moves so fast that the waves within the wind cannot ever make it back to the Sun, which severs their connection. Before the Parker Solar Probe crossed the threshold, remote images of the corona could only narrow down the location of the Alfvén critical surface to somewhere between 6.9 million kilometers to 13.8M km (4.3 to 8.6M mi) from the Sun’s surface. The Parker Solar Probe entered the precise conditions of the Alfvén critical surface 13M km (8.1M mi) from the Sun, or at about 18.8 solar radii.

During the Parker Solar Probe’s recent flyby, the spacecraft passed into and out of the corona several times, proving what some had previously predicted, that the Alfvén critical surface isn’t shaped like a smooth ball but rather has spikes and valleys. The surface is wrinkled. If scientists can determine where the spikes correspond to activity from the Sun’s surface, we will be in a much better position to understand how surface events affect the atmosphere and solar wind.

At one point, the Parker Solar Probe got as close as 15 solar radii (10.46M km / 6.5M mi) from the Sun’s surface. When it did so, the craft transited a coronal feature called a pseudostreamer. These are ‘massive structures that rise above the Sun’s surface and can be seen from Earth during solar eclipses.’ NASA likens passing through the pseudostreamer to flying into the eye of a storm. Inside the pseudostreamer, conditions are quieter. The conditions are quiet enough that the magnetic fields in the area determined the movement of particles, which further proved that the craft had crossed the Alfvén critical surface.

|

| This diagram shows the Parker Solar Probe’s distance from the Sun at different critical mission points. Credits: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center/Mary P. Hrybyk-Keith |

The mission aims to get closer to the Sun’s surface. Much closer. The eventual goal is to get 8.86 solar radii (6.16M km / 3.83M mi) from the surface. ‘I’m excited to see what Parker finds as it repeatedly passes through the corona in the years to come,’ said Nicola Fox, division director for the Heliophysics Division at NASA Headquarters. ‘The opportunity for new discoveries is boundless.’

To read more about the Parker Solar Probe’s mission, including its role in discovering the origin of switchbacks in the solar wind, visit NASA. The most recent discoveries are outlined in a newly-published paper, ‘Parker Solar Probe Enters the Magnetically Dominated Solar Corona‘ by J.C. Kasper et al. The next scheduled flyby is next month, and we’re excited to see what the Parker Solar Probe team discovers.