To celebrate Earth Day 2022, we’re revisiting some of our favorite environmental stories and interviews from the PopPhoto archives.

Nick Brandt’s 2016 photo book, Inherit the Dust, was his visual cry of anguish about the looming apocalypse for animals habitats in Africa. If the killing of animals continues at pace, the elephants, rhinos, lions and cheetahs will all but disappear. “I am embarrassed to use this phrase because it’s so corny and clichéd, but I want to make the world a better place,” he says.

The English born Brandt is a self-acknowledged environmental activist who has been shooting exclusively in Africa making eloquent and emotional animal portraits for more than 20 years. (On This Earth, and a Shadow Falls Across the Ravaged Land.) As Brandt watched both the animals habitats and the creatures disappear, he realized he “couldn’t in good conscience keep making money from the animal portraits without taking action.” In 2010 he co-founded Big Life Foundation with Richard Bonham, one of East Africa’s most respected conservationists. Big Life partners with local communities and currently employs more than 300 rangers to protect animals living on more than two million acres of land.

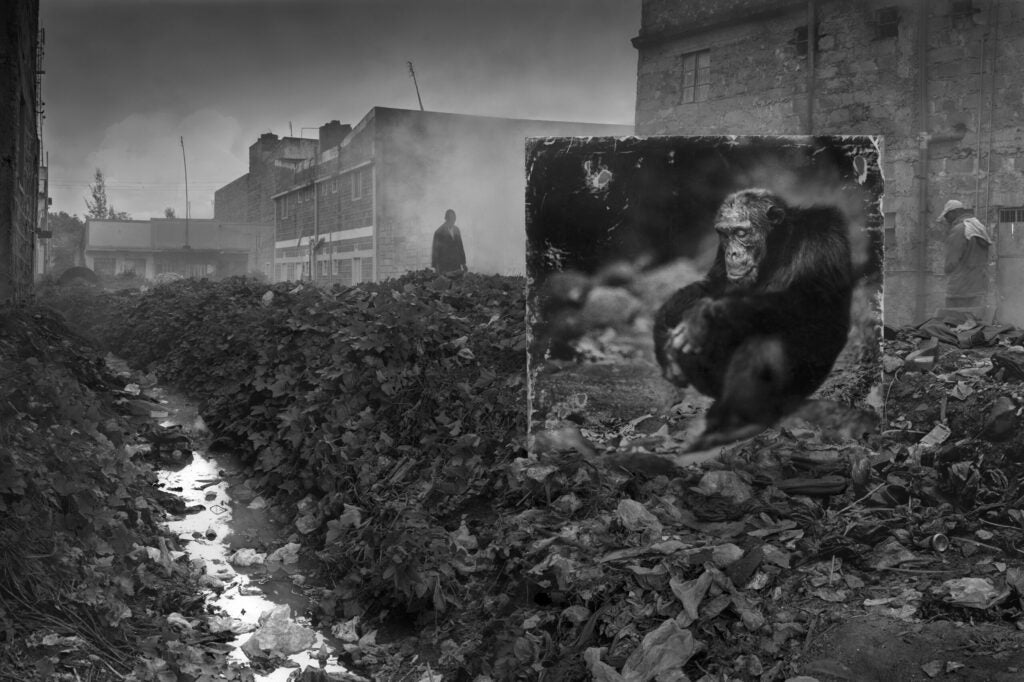

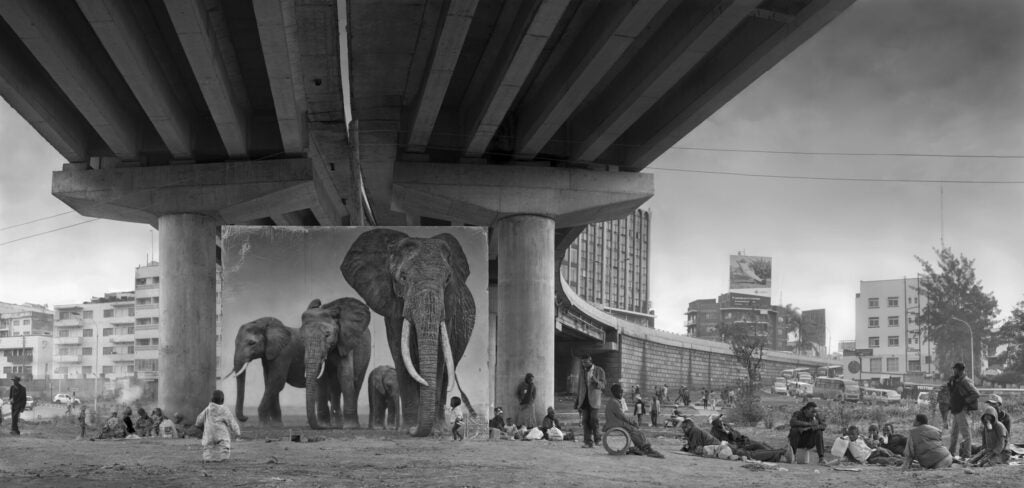

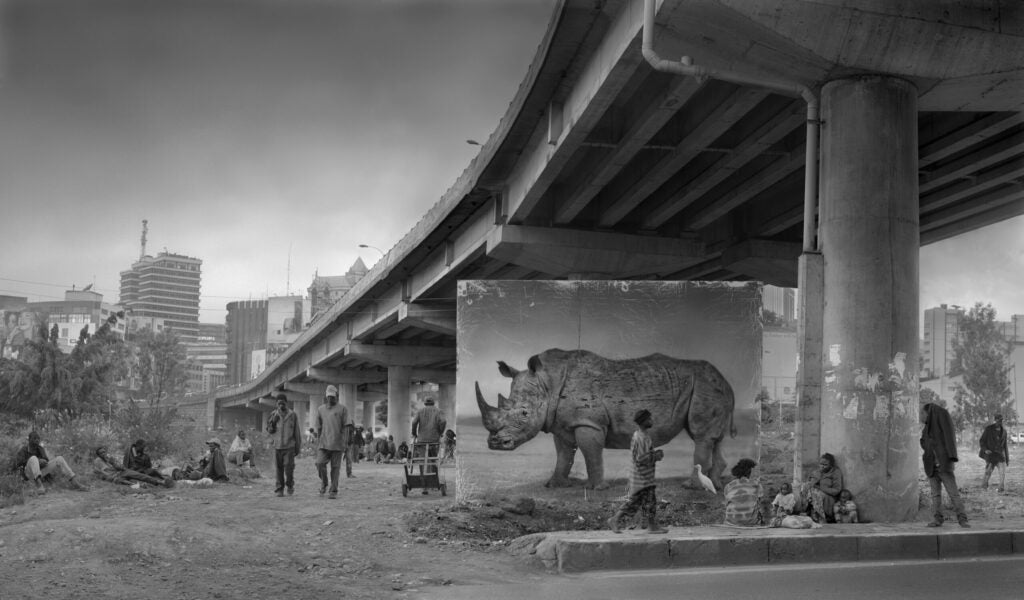

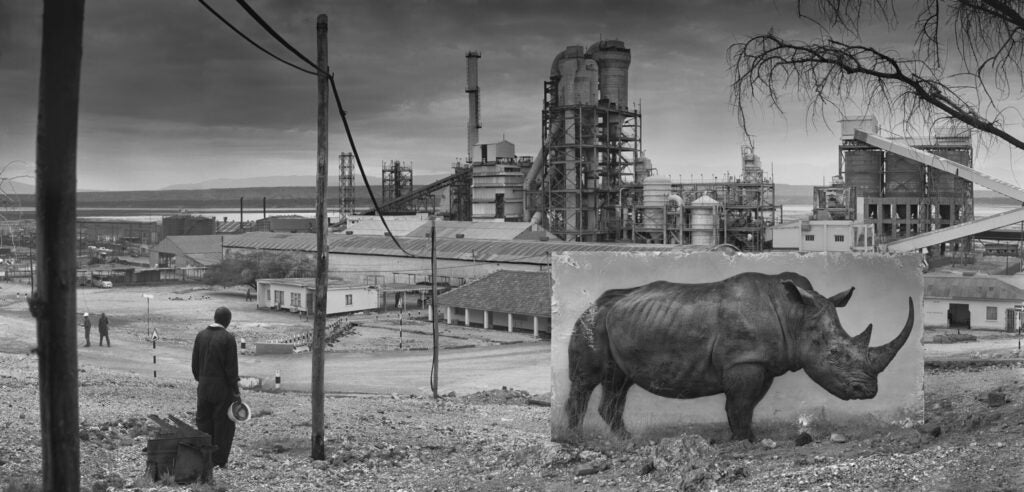

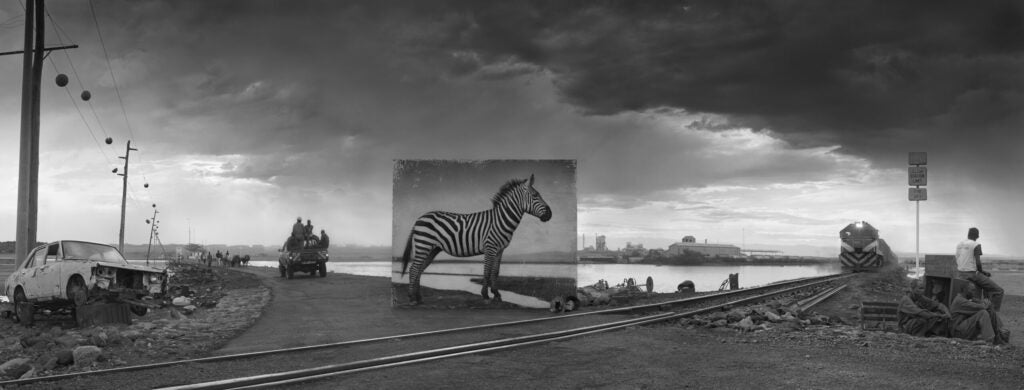

That epiphany was also the genesis of the idea to erect life-sized panels of the animal portraits, place them in dystopian urban wastelands or industrial sites in Kenya where the animals once roamed, and create black and white epic panoramas of the scenes. The resulting images are simultaneously beautiful and horrifying, because they illustrate the irreconcilable clash of past and present. The animals represent a time when the African landscape, filled with a plethora of species, was primal and glorious and seeing it would fill even the most jaded of us with a profound sense of wonder. The present is a world eclipsed by poverty and desperation, exploding with population growth gobbling up every inch of land for people to live on, farm or mine.

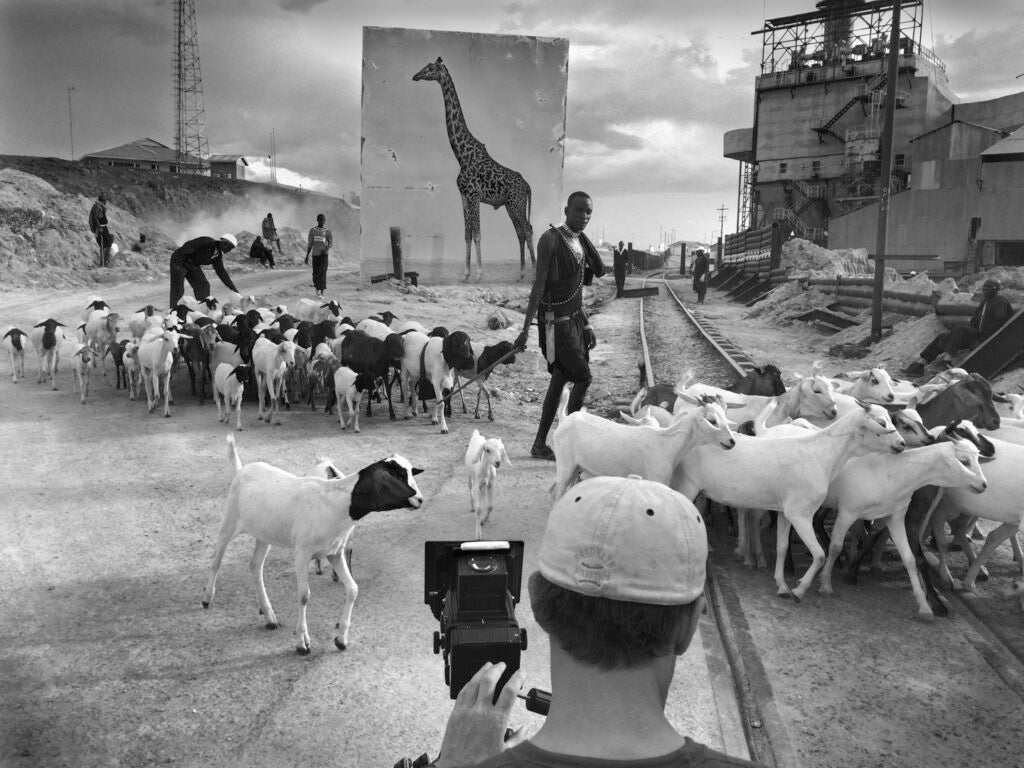

Animals and humans are both struggling to maintain animal habitats. Brandt culled his outtakes, made life size prints in California and built test flats 30 feet long on his property to see whether the animals looked correctly life sized. “Where you place the panel can totally change your perception of whether the animal is large enough,” says Brandt. When he was satisfied, the strips of images were shipped to Kenya to be mounted on site onto huge elaborately constructed wooden and aluminum flats. At times it took at least 23 men to install the flats to ensure they were level, tied down with sand bags, and the horizon lines in the animal images matched up with the actual horizon line in the scenes. With the flats in place, Brandt would wait with his Mamiya RZ67 Pro II for hours, sometimes days, for the perfect melancholy clouds and the ideal film moments. Later he meticulously stitched the images together in Photoshop to create the huge panoramas of animal habitats that were published by Edwynn Houk editions in a 13 by 15 inch book.

“The really tough part was waiting for the clouds,” says Brandt. “I went in the rainy season, but it is still Africa and you can go six days in a row with sunshine and no clouds. I had no choice but to wait, hoping that when the clouds finally came, something else interesting was happening in the frame.”

Film seems like a risky choice for a very expensive three-month location shoot in various African animal habitats. To ensure that his exposures were right, Brandt flew someone to London every couple of weeks to hand carry a couple hundred rolls of film to a certain small lab where film is still processed by hand. Even though the returned contact sheets assured him that the exposures were fine, it wasn’t until he was back home in California, scanning negatives, and deep into post production that he knew whether the focal planes of each frame aligned with the next so he could create the seamless panoramas. The obvious question is why not take the easier and safer digital route? Brandt’s answer— characteristically brash and irreverent—is that digital “stone cold” bores him. “Film just turns me on,” he writes in his book. “I covet the glorious surprises that are sometimes achieved by the magical interaction of light and film negative.”

He is turned on not just by the magical interaction of light and film, but also the serendipity of what happens when events are left somewhat to chance. On the first couple of days Brandt attempted to control every minute detail of the animal habitats, not surprisingly, since he is demanding, obsessive and meticulous. He hired a cast of locals to direct, but almost immediately, he realized it wasn’t working. “We were calling ‘action’ but what was happening was complete crap, just so staged and stilted that I realized the scene couldn’t be directed,” he says. “I decided to place one person somewhere in the frame for a size reference and wait for that perfect moment of staged and spontaneous action and interaction.”

Sometimes interaction meant no action with the picture at all. In most of the images, the contemporary figures move through the frame, picking up garbage, sniffing glue, and just walking down the street, seemingly oblivious to the large animal photograph, as if the animals were already ghosts. In one of the saddest images, “Alleyway with Chimpanzee,” a solemn chimpanzee sits with its head lowered in a trash filled alleyway next to what looks like a stream of fetid sewage. “The actual portrait was originally a quite neutral photograph, not particularly moving,” says Brandt. “In the new context, the chimpanzee seems to be lamenting the world in which it now finds itself.”

In one of the most compelling images of animal habitats, “Underpass With Elephants (Lean Back, Your Life is On Track),” Brandt has installed the image of a family of elephants under an overpass. New construction rises in the background, while homeless people anchor the foreground. Some are sleeping while others sniff glue out of empty water bottles. On the left side of the frame a toddler seems to be walking towards the elephant image. On the right, a very small child has walked up to the image, trying to touch the elephant’s trunk. In the distance we see a billboard of a man relaxing on a bench with the ironic slogan, “Lean back, your life is on track.”

“Nothing compares to the excitement of shooting on location when the unexpected happens,” says Brandt. “In the ‘Underpass with Elephants’ image suddenly on the right side of the frame this little child walks up and touches the image. It was one of those ‘where the hell did he come from’ moments.”

The urban animal habitats, where the huge panoramas exist, were not easy to work in. The crew spent 12 days at a dumpsite in Kenya, which was a toxic, smoking pile of waste where locals scavenge for food. In one image from this dump, “Wasteland with Lion,” the flat has been installed so the lion appears to be lying in the trash, lethargically surveying the wafting smoke and the people picking through the dump for scraps of food. In the case of the lions, H=humans have destroyed both the animal habitats and the human living situation.

One of Brandt’s favorite images, “Wasteland with Elephant,” was taken in the same dump. The image of a large old elephant with ragged ears that mirror the ragged edges of the flat looms large on the left hand side of the frame. The flat was installed deep so the elephant’s foot looks as if it is touching the actual foreground and he is walking out of the flat into a world in which he knows he cannot survive. The image garners emotional resonance from the sky, layered with light clouds just at the horizon, but dark gloomy clouds at the top. It produces a foreboding image of animal habitats.

“This is a really great example of how under a cloudy sky not all light is the same,” says Brandt. “The stormy clouds in this image inform and affect the light on the ground. There was something apocalyptic about the combination of the rising smoke and the clouds, even though not much is going on with the people who almost blend in to the landscape.”

The post Nick Brandt’s panoramas put the clash between wildlife and urbanity in stark relief appeared first on Popular Photography.