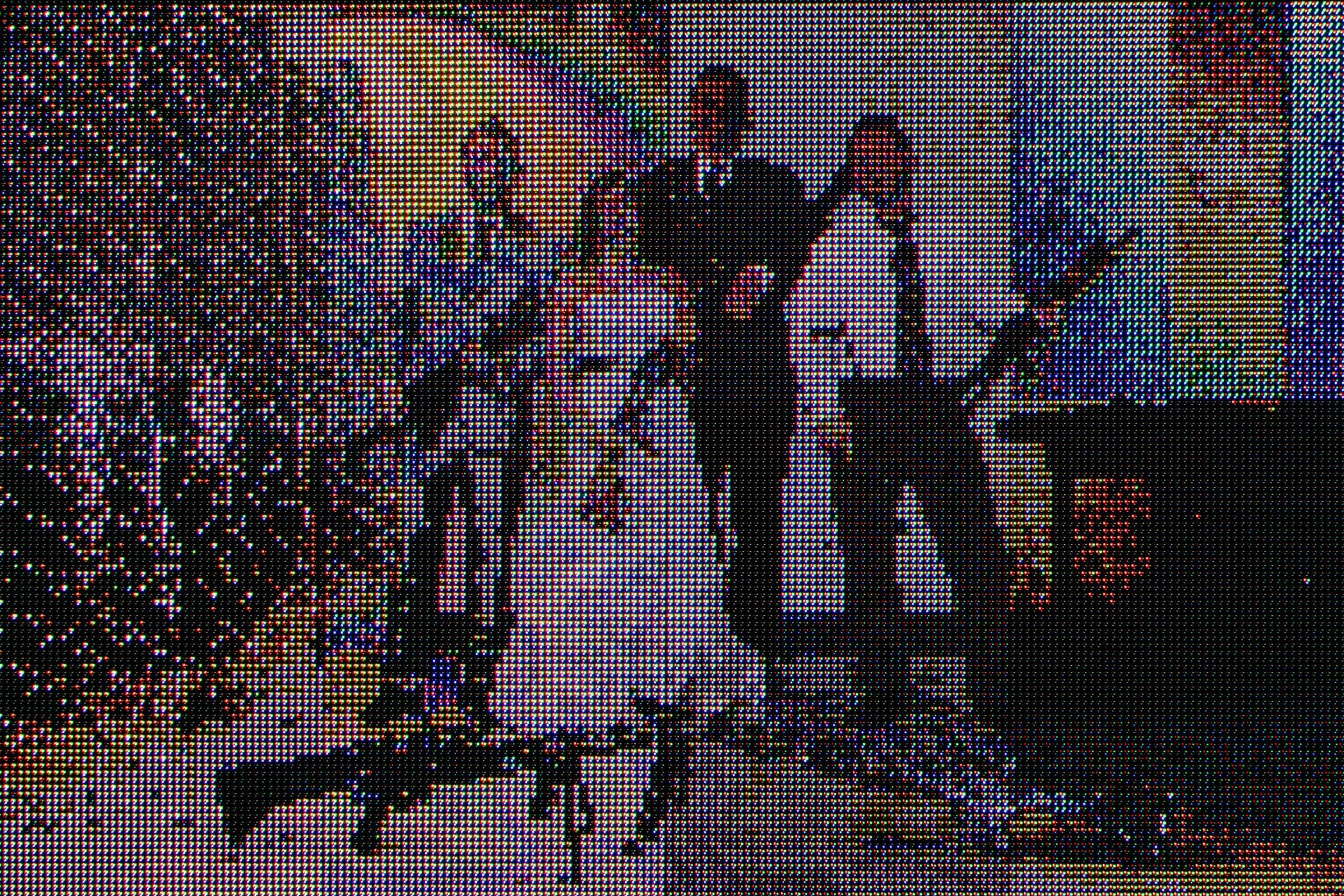

Mosul. Iraq. 2006. © Peter van Agtmael

Peter van Agtmael has been obsessed with military conflict since childhood. A member of Magnum Photo, his career kicked into high gear at the age of 24 when he began covering the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan as an embedded journalist. To this day, Peter continues to document these conflicts and their impacts, both in the Middle East and at home. His images are often accompanied by lengthy captions that occasionally take on a narrative tone.

We caught up with Peter, whose recent show at the Bronx Documentary Center, “Look at the US,” spans two decades, and seeks to shine a light on the complexities of the post-9/11 era, which is certainly no easy task.

Here we talk about both his initial attraction to war and what keeps bringing him back to conflict zones. We also touch on the war in Ukraine, the importance of fixers, why captioning images is a must, how and when to involve yourself in the coverage or narrative, and why his next project will be (a little bit) on the lighter side.

Peter van Agtmael’s show, “Look at the USA” is up through June 26 at the Bronx Documentary Center in New York City. You can also pick up one of his recent photo books, including 2021’s aptly titled “Sorry for the War,” here.

Tell me about your most recent exhibition, “Look At The USA”.

It’s essentially a culmination of the last 16 years of work I’ve been doing, looking at fault lines in the post-9/11 American world order. And it’s a show that’s divided partly chronologically, partly thematically. It’s a tough, big subject to wrestle down. I think there were a few premises when I started making the show; one was how do I tell this history as I understand it? How do I tell the history as I saw it? Where does my personal history serve as a storytelling tool that’s useful and when is it more important to lean on how I perceive the era unfolding?

Beyond that, as I worked throughout these last almost two decades, there came up a lot of questions about not only what this country was becoming in the post-9/11 era, both at home and abroad, but what had led us to this point? What was the character of us as Americans that could allow us to go into these wars, both so recklessly and so ignorantly, and then ultimately still kind of specifically? What impact did that have on the culture, on the society, and what was it about the culture in society that led us to this point?

How did this project start?

When I started this work in 2006, I was 24 and there was no plan, really. I didn’t anticipate what this would become. I started with the simple idea of wanting to go to cover the war in Iraq, which I saw as one of the formative moments of my generation. It followed in the wake of 9/11, which had a deep effect on me personally, just witnessing the world change and the world get shattered, or at least the world as I knew it. I just started with the simplest of plans; I thought it was going to be the formative war in my generation the way the Vietnam War was the formative war of my parent’s generation. [I was] not quite connecting the dots that when you are in a society that has an all-volunteer army, [one] that generally draws from the margins of society, actually, most people were just going to move on [from the war] very quickly. And so in some ways, it became that.

Related: Antigone Kourakou’s surreal exploration of nature & humanity, plus other photo books for summer

And the process essentially became that. What started with this simple idea, I want to cover this war, became [more about] who are we fighting and what’s the character of the Iraqi and Afghan people? What are these cultures? Where are these societies? Who are the people fighting these wars from the American perspective? Where do they come from? Then that raises questions about geography, which raises questions about class, which raises questions about race, and then all that intertwines with nationalism and militarism and politics and myth-making, and also this idea of manifest destiny and our history as an empire, both domestically and abroad. Long story short, I guess it’s a very simple question that led to a lot of very, very complicated questions. Questions that are difficult under the best of circumstances to reconcile—and maybe particularly difficult to visually reconcile.

So simultaneous to the taking of the pictures, writing and words became important, both to offer a context for what was happening and a personal context of why I was doing this thing. This became an exercise in questioning myself and laying out my own vulnerabilities and uncertainties, partly because I don’t believe in the authoritativeness of either photography or journalism. In talking about one’s own experiences and the flaws of moving through that experience, I guess I could trust myself better to try and tell the story [that way].

That being said, I tried to tell the story carefully. So, by using myself as a storytelling vehicle, I could go deeper into the history of these events as I saw them. Also, right around the events, [I could add context to] the things that can’t be photographed. What comes before? What comes after? What sometimes is happening can’t get condensed properly down to, one or two split seconds. In the end, it’s a show of hundreds of odd pictures. The books are a few hundred pictures in total, but what those amount to is really only a few seconds of time.

I know you’ve spent time embedded, were you with only the U.S. military or the Iraqi and Afgan militaries too?

I’ve spent more time embedded with the U.S. military for sure, but I’ve done small embeds with the Iraqi army and the Afghan army as well. But by the time [I was able to embed with them], I was turning my attention more towards the Iraqi and Afghan [citizens]—I was more interested in the civilian perspective than the military perspective. So I didn’t spend as much time with those militaries directly. I spent a lot of time with them when they were with the Americans because those militaries were very tied to one another. The American military was training the Iraqi and Afghan militaries throughout these wars. So I’d be with Iraq or Afghanistan military, but with the American army alongside them.

How did those embed experiences compare? What was it like being with the U.S. military?

The experience differs in so far as the American military, in general, is pretty bureaucratic and there was a system connected to embedding where you fill out certain forms and you email the right people on the chain of command, and you could get access to units on the battlefield for a certain amount of time.

From the early days of the war until about 2009, 2010 or so, the military was very open about their access. You could kind of get dropped off at a unit somewhere for a month or six weeks and they pick you up at the end. Until then, you’d have access to everything that unit was doing, as long as their commanding officer was on board with having an embedded journalist. Usually, they would put you with a company commander or platoon commander who was cool with the media.

But that access to the U.S. military didn’t last?

At some point, then those embed rules changed. They basically shut off all access to the battlefield, and especially to pictures of injured or wounded soldiers. That was a pretty dramatic choice and it really affected coverage. It would’ve, in theory, caused a controversy. But at that point, no one cared about the wars anymore. So while it was a big deal in the journalism community to some degree, because the war coverage had largely ended and people had moved on, it just kind of happened and that was that. Access was more or less cut off. Or if you got access, you’d get one or two days of access and you’d be escorted everywhere.

You couldn’t see the things one would necessarily want to see. Then when I did those embeds still, those pictures became to some degree about trying to find the cracks and the holes in the way the message was being controlled.

What was it like being embedded with the Iraqi and Afghan militaries?

With the Iraqis and Afghans, it was much less formal, in a way. It was a question of who you knew and if you had a good fixer who knew some colonel who was willing to take journalists on. You could just kind of post up with them and they’d take you along. In those cases, you could kind of go as deep as you had the stomach for. But tactically, the U.S. military relies much more on force protection. They’re trying to fight, but they’re also trying not to die. So, the tactics are based around creating, in many ways, as low a risk situation as possible. Iraqis and Afghans are pretty different in that regard, tactically sometimes. It was a little bit more precarious, by and large. So I wasn’t doing tons of time [with those militaries] probably for that reason, because the risk level was high. By the time that option was open to me, I was also less interested in covering the front lines of the wars.

You’ve made many trips to the Middle East to cover the conflicts there. Tell me about what keeps bringing you back?

The Middle East? I mean, it’s a hard question. Partly, I’ve always been drawn to war since I was a child. I think a lot of young men, young boys, have an attraction to the military and the notion of war, but few pursue that path. Most people grow out of it in one way or another, or other priorities take form. For me, it was something that just…it always persisted. I really felt strongly, from an early age, and then with increasing intensity. It was something that, for whatever kind of dark and naive reasons, I needed to see for myself. Once I did see and experience it, I wanted more of it in a way, and that was, partly for ideological and political reasons, why I was good at this work. I believed in the task and the power of journalism and believed that it had something to contribute and something to say. Also, because I was a good fit, it made me feel like the person I thought I was supposed to be.

I was good at it. I’d never received that kind of, in a weird way, positive feedback; positive for something so troubling, and that was seductive. But over time, it took its toll emotionally and spiritually, and intellectually to some degree too, in the sense that I also started to get a little bored of it at some point. I was taking these enormous risks, but not getting this kind of… it wasn’t moving me forward in the photography or storytelling anymore.

So, over time, I started easing out of it. Some bad experiences, near-death experiences, helped usher that along the way. I think it’s always going to be part of my life. I still cover conflicts to some degree, but not as aggressively on the front lines as I used to.

It’s always one of the unanswerable questions. What draws one again and again? I’ve never been able to sufficiently answer that for myself. It was something that was deep in me and now luckily is not nearly as deep in me as it was.

So, at a certain point, you transitioned from covering war to covering its impact. Can you tell me more about that transition?

Well, it was a transition, but it was always back and forth in a way, too. What I became interested in just kept expanding. As covering things at home became more and more interesting to me, the war part got slowly squeezed out. Then I would go back. At times it felt necessary to the work I was doing.

I tried desperately to get in during the withdrawal from Afghanistan last summer. I’ll go back to Afghanistan finally in a month or so to finish the work I wanted to do then. During the withdrawal itself, that was a very, very dangerous time to go. I wasn’t particularly keen to be taking those sorts of risks but it was such an important, historical moment. The trajectory of these wars and my coverage of them, it seemed like a risk that I could justify taking for myself and my loved ones. Going to a place like Ukraine right now does not fit into that for me, because I have no history of covering that conflict.

If I had been covering it for the last eight years, it’d be one thing. I’d want to probably continue the work I’d already been doing. But I haven’t been. I didn’t feel it was appropriate to go and take those kinds of risks if I didn’t have a story I really deeply needed to tell. But the temptation is always there. Not to oversimplify it but I think it’s like the way someone who’s an alcoholic or a drug addict feels, a little bit like you can quit the thing but there’s always going to be a little devil whispering on your shoulder.

You mentioned Ukraine. Can you provide some insight, as much as you feel comfortable, about what it’s like to be a working photographer in an active war zone?

Every war has its own character to it. Embedding with the U.S. Military, for example, was very different than, say, embedding with Iraqi soldiers or doing stories about Iraqi or Afghan civilians, right? And sometimes, some places are, despite it being war, quite safe. Others are extremely dangerous. Sometimes that difference is just some invisible barrier you can’t even see. But the thing that holds true in all of them is that you have to know exactly what you’re getting into, where you’re going and who you’re going there with, essentially.

This is where fixers become the critical part of any journalist’s work. You really have to partner with someone on the ground who’s knowledgeable and not risk-averse, but also not a sort of reckless risk-taker, and who deeply knows the lay of the land. Hopefully, [with a fixer’s help] the powers that be can grant you more access because so much of photography is really about access.

Your photos tend to have an almost absurdly disorienting visual quality to them. And I mean that in the coolest way possible. Can you tell me a little bit about what you’re looking for when making pictures?

Yeah. I mean, it’s a good question. I don’t know if I’m looking for anything specific in a way. I’m definitely attracted to the absurd. I’m attracted to resolving chaos within a frame. The more the years go by, the more I’m attracted to complex images that say several things at once, sometimes things that seem to be in opposition to one another. I think I’m attracted to the challenge of resolving a complicated event into a coherent frame. It’s just difficult to do visually. It also offers a certain kind of spontaneity.

If there’s a lot going on in a picture, you could never be ahead of the action in a way. You just have to get yourself to that place and keep clicking and hope for the best. Sometimes it works out and sometimes it doesn’t, but I like the moments in photography that force me to let go of my control of visualizing the scene. Those types of images that you mentioned are the kinds that really do that, where I’m never fully in control of what I’m photographing. But that being said, I think I like simple images as much as complex ones. I think that as one evolves as a photographer, as I’ve evolved as a photographer, I’ve gone from not being able to take complicated pictures to developing the skillset to do so.

But the thing that drew me to photography—the singular moment, the singular detail—it still attracts me equally to this day. There are many ways to tell a story in pictures and sometimes that relies on complicated images and sometimes [it’s] simple images. Pictures are very emotional. Sometimes they’re a little detached. Sometimes they’re absurd. Sometimes they’re for tasks. Sometimes you’re showing a big scene. Sometimes you’re just showing the details of somebody’s lips or hands. The more I dive into photography, the more I want to expand my visual language because ultimately, it’s all in the service of storytelling. I think complicated storytelling that nonetheless has a clear through-line, that’s the kind of storyteller I want to be doing and keep pushing forward.

You mentioned you’re headed back to Afghanistan in a month or so. Can you just give us a little peek into what you’re working on next? Do you have any other projects coming up?

I’ve been working on a book throughout the year with my partner that really looks at a lighter subject on the surface. It’s about the relationship in the U.S. between food and culture, and history and society. And so we’ve been finding a lot of little stories related to American food that speak to the larger questions of American identity. It’s a way of looking at a big picture question that always interested me, who and what are we as a nation, but coming at it from an angle that’s a little more accessible.

I think part of the frustration with the more serious work—I mean, I think this work is serious too—is it has less appeal to someone who might not be a photographer. Ultimately, I’m chipping away at these dark stories over the last 16 years. I fear that when I try and pull them all together on my own terms, through the books and shows like this, they’re inevitably only reaching a very narrow audience. And so [this new project] is partly a storytelling tool to try and bring a broader audience into the things that I think are worth communicating.

And then the Afghanistan trip is sort of the logical end in a way to this post-9/11 work that I’ve been doing, on some level. The post-9/11 era, it’s here to stay. It was an inflection point in history that everything kind of emanates out of. But with the end of the war in Afghanistan, I think a certain phase of this era did end, and a new one is now beginning to unfold. But with the Taliban back in control of the country and the ruins of what was left behind, it kind of seems to be a symbolic end of the work.

That’s why I want to go back.

The post Peter van Agtmael grapples with chronicling the post-9/11 era appeared first on Popular Photography.