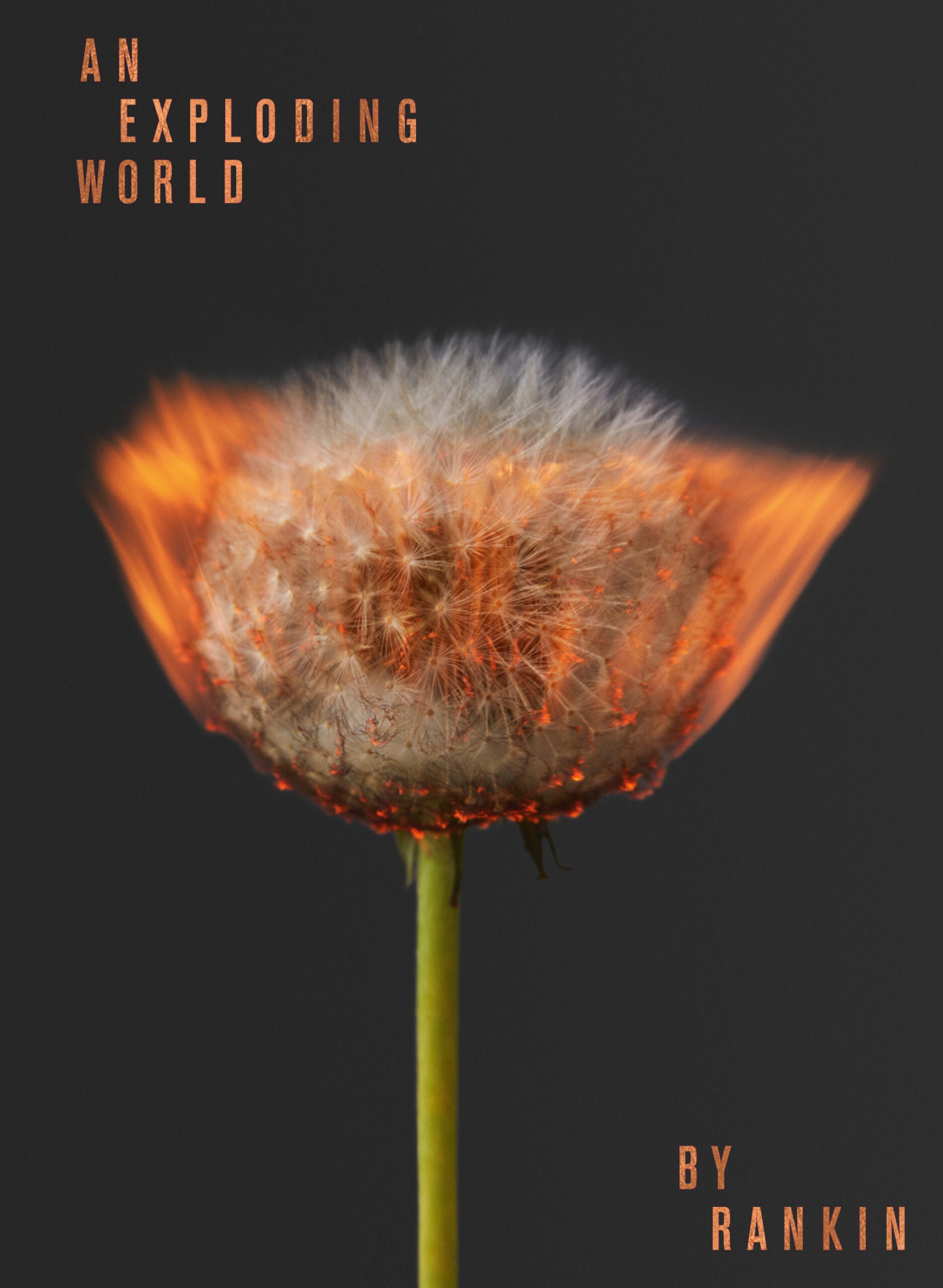

Rankin has photographed many of the big names in fashion, music, and society. Known for his portraits of Kate Moss, David Bowie, and Queen Elizabeth II, he is also at the head of a creative agency with dozens of employees. When lockdown hit in March 2020, and Rankin could no longer work in his studio, he set up a camera in a spare room of his country house and started photographing dandelions. Then he started setting them on fire.

You lead a very busy life at your agency. When lockdown hit, was it a big shock?

It was a really big shock. I don’t think I was unusual in my experience of it. I was very anxious. I didn’t think I’d spent a day of work on my own for 25 years. And suddenly, I was on my own, in my spare room, taking photographs of flowers.

I had tried to photograph flowers so many times and had never been really that successful. And then suddenly, they were the only things I could photograph, apart from my wife.

Why did you choose dandelions to photograph?

During the lockdown, I first started photographing dead flowers, but I’d been looking at dandelions for so long… I live in the country and they’re everywhere; I’d started to see how many different versions of dandelions there were, and I’d begun to become a little obsessive about them.

I didn’t really think of it as a project, I just thought of how incredible nature is, but at the same time how fragile. [Dandelions] sum that up in a really brilliant way. It’s almost the most efficient natural machine that you could ever make. If you pick one up and blow it and you see the seeds flow, it’s absolutely extraordinary the way it works.

I was two or three weeks into lockdown. I started to look at them and wonder how I could bring them into the photos. I started taking pictures of them as they aged. And then I tried to burn a few and film them. It was really hard to do and make it look good. So I devised a way of shooting them. I was photographing these things at peace. They were very peaceful, almost morbid in a sense, quite celebratory of life, and very reflective of how I was feeling about aging.

The first time I photographed one, and it blew up, it looked like a nuclear explosion. And I just thought, this kind of reflects how my feeling is about the world at the moment.

On a moral level, I didn’t feel very good about destroying something that’s absolutely perfect in nature. But I did feel really good about how it symbolized so many things, about how I was feeling, and how I think a lot of people were feeling.

So this was a kind of liberation for you personally?

Related: Cig Harvey explores grief and death through the quiet beauty of floral life

Yes, through taking the pictures immediately, because there’s something very visceral about it, but also through [creating] the set of images. When you see them big, they’re amazing. Some of them are six feet by four feet.

It was really strange for me to do something so repetitive. I don’t normally do that. I jump around a lot, I am not somebody that is easy to pin down as a photographer because I love photography so much. I decided very early on that having one style of photography would be very limiting. I really get bored doing the same thing. Whereas with this, that was what was amazing about it. I must have photographed 500 of these dandelions. It was almost addictive because it really released something in me.

How exactly did you shoot these photos?

I was in the spare room and I was using natural light. I was shooting on a Canon EOS-1Ds at the highest shutter speed I could get. ISO was always 100 because I wanted to blow them up really big. I was shooting about 12 frames a second.

What I’d tried doing flowers before, I’d always been trying to put jeopardy into them in some way. So I sometimes had them in vases on the edges of plinths, or I had them leaning up against walls, trying to put drama into them. Within a week, I was thinking about them as people. I was creating characters, I was giving them names, talking to them. That really got me excited, because I was taking what I would do in a portrait session and bringing it to these photographs of the flowers.

If you take flower photos, you can approach them as you do with portraits because they’re like faces, and you work with lighting the same way.

That’s exactly what I did. I got that idea really early on. And it was so natural, I didn’t force it. It just came from me not photographing people and suddenly changing what was in front of my camera.

The British call the dandelion seedhead a “clock.” Did you think of that time element when making these photos?

Photographers can’t not think about time. For me, personally, it’s there on my shoulder all the time. I think in fractions of a second and capturing fractions of a second with the intention of having them hopefully live forever.

A photograph is a slice of time, but in these burning dandelions, you have the dynamism of the fire knowing that it started and it’s going to end.

Absolutely, this is what the flowers embodied for me early on: the passing of time. That’s why I started with the almost dying flowers with petals that looked like decrepit skin, because the lifespan of the flower was really obvious to me. I was very aware of it at this moment when all our lives were being turned upside down.

I’ve always been obsessed by flowers, like every photographer is, so I’d always had a bit of a love for the dying, the drying of a flower. And there’s a beauty in that. When that was happening, they had a pertinence that was underlining what we were all going through. And then I started to think that this is the best representation of how I’m feeling as a human being.

With dandelions, it’s a kind of destruction of time, like a nuclear explosion, like how within an instant something can go from being completely alive to be not alive. And you can see life being lost in the pictures. That’s, a powerful metaphor, but at the same time, it is visually stunning.

See more of Rankin’s work here, and pick up a copy of “An Exploding World” here.

The post Rankin’s flaming dandelions are the perfect metaphor for ‘an exploding world’ appeared first on Popular Photography.