All images © Mik Critchlow

The social documentary photographer, who passed away last week on his 68th birthday, told the story of his industrial hometown of Ashington with unparalleled insight and sensitivity

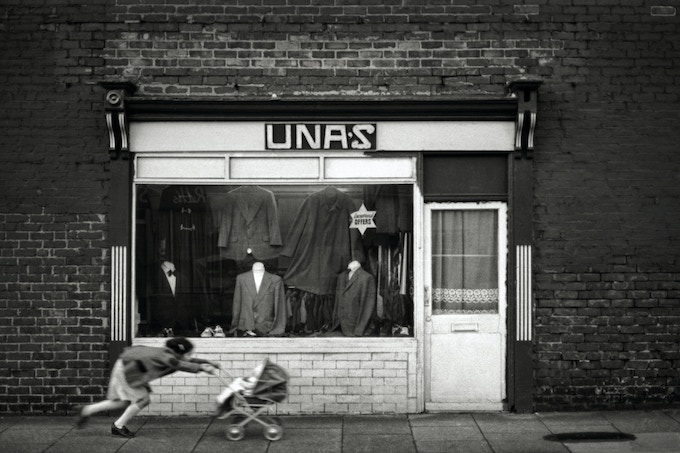

To remember Mik Critchlow is to tell the story of a place, a man whose life and photographs existed in symbiotic union with Ashington – his ancestral home, inspiration, and artistic stage. The social documentarian made pictures in the North East for over four decades during a time of burgeoning and then decimated industries, resulting in projects which followed the rise and fall of a whole culture and way of life. From blackened collieries and miners’ picnics to the decline of the shipping industry, Critchlow operated from within working communities – a trusted voice documenting social change for future generations.

Born in Ashington, Northumberland in 1955, it was “almost expected” that Critchlow would follow his three generations of Critchlows working down the Woodhorn and Ashington pits, he recalled grandfather and great-grandfather down the nearby Woodhorn pit, he recalled. His grandfather had worked in the colliery for 52 years, while his father began working at the Ashington at the age of 14, completing 45 years of service in 1985. Critchlow’s eldest brother was a miner at Ellington Colliery for 25 years.

The young Critchlow took a different path, joining the merchant navy at age 15. “By the time I was 18 I’d been around the world a couple of times,” he remembered. “The Med, Australia, India, the USA. The furthest north was Baffin Island.” While travelling, Critchlow developed his interest in drawing, pursuing a correspondence course in art history through the Seafarers Education Service. Upon returning to the North East in 1977, he signed up for a foundation course in graphic design and art history at Ashington College.

“They thrust this 35mm camera in my hand and told me to take pictures,” Critchlow remembered. One exercise in the photography module was to go out and take images of the angles of local buildings. But Critchlow’s eye was drawn to the people who inhabited these spaces – the passers-by and varied characters. His photography lecturer “hated his stuff,” Critchlow recalled, complaining that he had veered from the brief. But his art history teacher recognised his ambition. “You’re doing social documentary photography here,” he told Critchlow. Almost by accident, he had found his form. His subject was all around him, and Coal Town, his long-term project about Ashington, was born.

Critchlow’s photographs show industrial life in the half-light, the shadows of welfare clubs and pubs, back alleys and church halls providing space for his characters to go about their business. The variety of settings in Coal Town speaks not just to Critchlow’s photographic appetite, but also to the trust that existed between him and his subjects. Women allow him to photograph them having their hair done; men barely look up as he captures them playing dominoes; others laugh in the changing room baths after a match at Ashington Football Club. His photographs of children are particularly well-observed, documenting their playtime at school and in the streets with a genuine belief in the importance of their lives.

“They showed me that ordinary people’s lives could be important and could be seen as art”

Critchlow was initially inspired by The Ashington Group of artists (also known as the Pitman Painters), having seen an exhibition of their works at Grundy Art Gallery in Blackpool in 1977. The collective was made up of local miners who came together in 1934 to pursue artmaking, mainly through sketches and vibrant, detailed paintings. “They recorded their lives with such honesty, painting the ordinary, the mundane, the everyday,” Critchlow recalled. “They showed me that ordinary people’s lives could be important and could be seen as art.” It was a philosophy Critchlow lived by for his whole career. When local people would query why he was photographing them, he would tell them that they had created the wealth in Ashington; that they were an important part of its history. “Every frame’s like an act of remembrance, for future generations,” he said. “People trusted me. I was part of the tribe.”

Around the same time, Side Gallery in Newcastle was developing its programme, having shown photographs by Graham Smith, Chris Killip, Homer Sykes and August Sander in 1977, the year of its opening. Critchlow visited an exhibition of works by Henri Cartier-Bresson the following year, a travelling archive from the Victoria and Albert Museum organised by Killip. He became friendly with the gallery team, gratefully receiving their mentorship and recalling the impact of Tish Murtha’s Juvenile Jazz Bands at Side in 1979. His work was exhibited at the gallery for the first time in 1987, and then several times thereafter, most recently in 2019 in Work & Workers alongside Daniel Meadows, Graham Smith, Walker Evans, Nick Hedges and a long list of renowned documentarians.

When Killip had trouble accessing the seacoaler community of Lynemouth Bay in the late-1970s, it was Critchlow who introduced Killip to his cousin, Trevor, who in turn gave Killip access to shoot there for two years from 1982. Fourteen pictures from Killip’s Seacoal series were included in his book In Flagrante in 1988, while Critchlow’s own Seacoalers photographs show the toil – and beauty – of the workers and their daily rhythms. Using horses and carts to transport the coal, they represent a different time, caught between tradition and impending modernity. “They were suspicious that anyone with cameras worked for the Social Security,” Critchlow remarked. But they trusted Critchlow, his liaison and artmaking based upon respect and resolute aesthetic judgement.

Coal Town was published as a photobook in 2019 by Bluecoat Press, and an exhibition ran in 2022 at Woodhorn Museum on the site of the old colliery, which closed in 1981. The book reveals Critchlow’s strengths as a portraitist – the ability to lift subjects momentarily from their surroundings without entirely erasing their livelihoods and social contexts. Colin Wilkinson, founder of Bluecoat Press, remembers Critchlow’s sensitivity in particular. “Tom Stoddart called me shortly after its publication to ask why the Miners’ Strike of 1984-85 had not been included,” Wilkinson says. “Mik was unequivocal in his response: even after 35 years, memories of the strike were so bitter, he knew that inclusion of photographs would only cause great pain.”

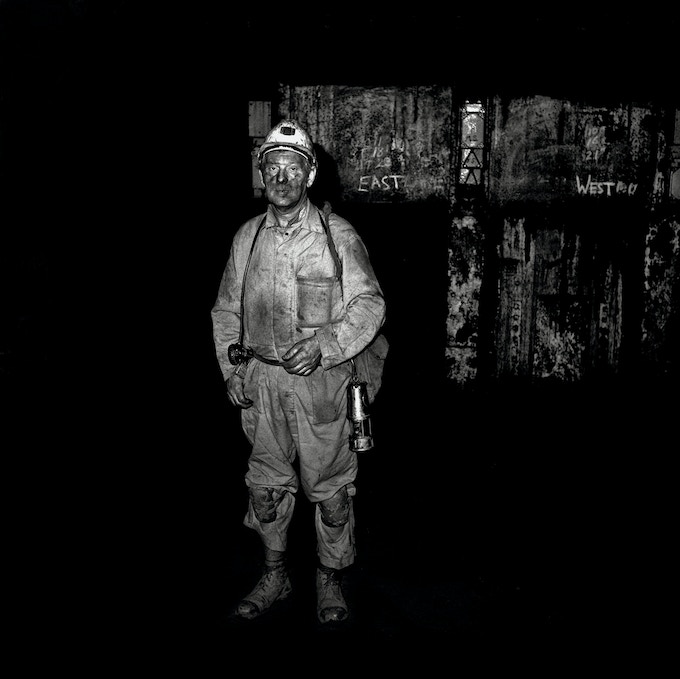

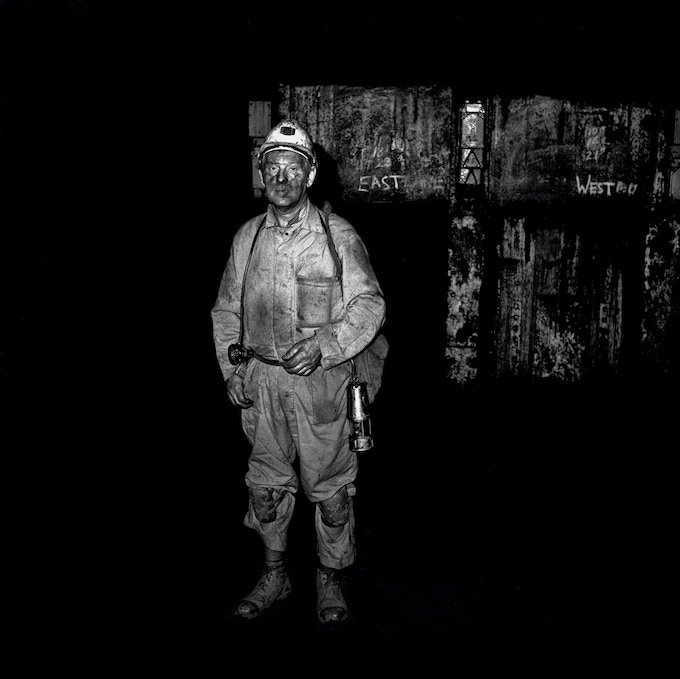

It is natural that several of Critchlow’s photographs would transcend his vast archive, becoming emblems of the period he witnessed. ‘Last Man Out’ shows colliery deputy George Miller Davison leaving the mine for the last time in 1981; his photograph of his father “crying into his beer” on the day of his redundancy is perhaps the most poignant. “My father always said he’d been left on the scrapheap,” Critchlow observed. He died of emphysema, a result of years of dust inhalation. “There was such an incredible sense of belonging,” Critchlow remembered of the mining communities in Coal Town. “It was a shared existence, everybody had nothing, they all had nothing, yet it was rich in humanity.”

An accomplished blues guitarist and, later in life, a music shop owner in Ashington, Critchlow’s legacy is secured through his images – and the fondness with which he is remembered in the North East and beyond. The testimony of artist Narbi Price, who studied the Ashington Group of painters, reflects Critchlow’s achievement in emulating the group’s humanity. His photographs are “more than just social documentary,” Price says. “They are beautiful time capsules that elevate the everyday into something else, something that speaks intensely of what it is to be human.”

The post Remembering Mik Critchlow, the North East’s great narrator appeared first on 1854 Photography.