Atiba Jefferson is a legend in the world of skateboard photography (and skateboarding in general). With more than 25 years of experience behind the lens, his work has and continues to grace the covers and pages of nearly every major skateboard magazine known to humankind.

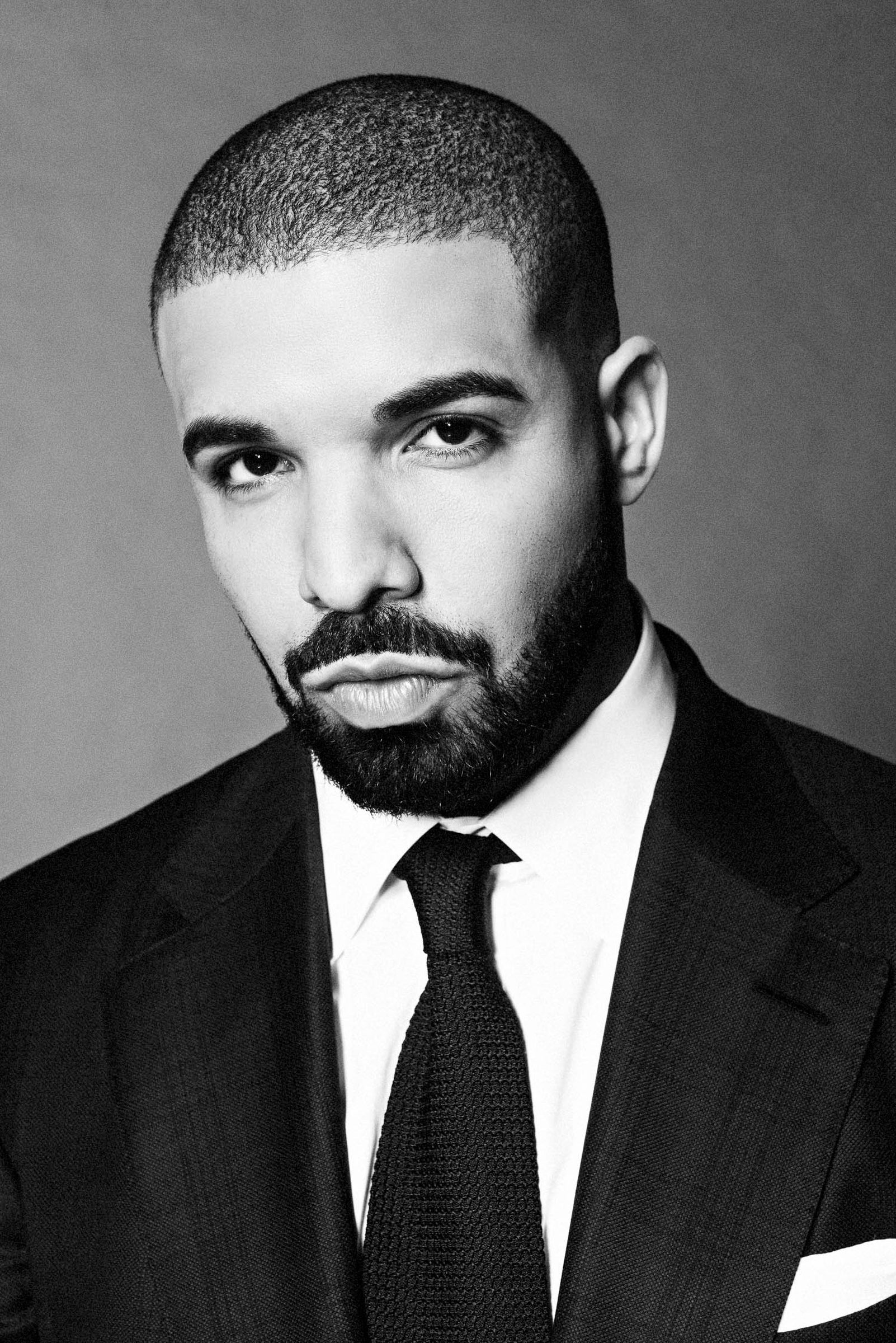

But don’t hold him to just skateboarding. The Los Angeles-based creative also moonlights with the Lakers, shooting everything from games to player portraits; works as a live music photographer, touring and documenting some of rock, pop, and rap’s biggest acts; and is a highly-coveted studio portrait and lifestyle shooter, known for collaborating with seriously-impressive brands and seriously-intimidating celebrity clients.

Perhaps more importantly, though, Atiba is a super-positive dude who radiates a DIY energy and a genuine sense of excitement. Here, he reflects on his career as a Black skateboard photographer in a white-dominated field; plus, we chat about the importance of being bold, the significance of mentorships, the magic of the darkroom, and what it was like to cover skateboarding’s Olympic debut.

Related: How Getty covers championship basketball with a small army of cameras—and robots

Which came first, your passion for skateboarding or your passion for photography? And when did you start?

Skateboarding. Skateboarding led me to so many things in my life: photography, art, music, culture, traveling, everything. I started skateboarding at 13 years old, so 1989.

How old were you when you first picked up a camera and what model was it?

It was my junior year of high school. So I was 15. The very first camera I used, and this is really funny because I have it, hold on (holds up a plastic-looking camera). It’s not the exact one but it was for a photo class and I remember you could take out a Pentax K1000 or this camera, a Canon Snappy Q. It was those two cameras. It was just whichever you were able to get. So both of those cameras were my first cameras.

And this is obviously still the film era, so you’re doing the darkroom.

Oh yeah. Oh yeah. Oh yeah. There was no such thing as digital. So yeah, it was strictly darkroom. And that’s what really attracted me to photography is seeing prints being made and the magic of that.

Where was your first skateboard photo published and do you remember the skater/trick?

My first photos were in Slap magazine. Local skaters, it was Danny Barone, one of my still really good friends, and this dude Mike Ambrose. So it was a collage of photos from people who contributed. It was their photo Graffiti section.

So that was a foot in the door, how did your skateboard photography career progress from there?

Let me say it one more time, it was one of those things where I sent photos to Slap. That was my first time. Then I was working at a skateshop and I would call Transworld [skateboard magazine] to order it and I would talk to Selema Masekela. He worked in sales. Back then, my friend had sent pictures to Grant Brittain (the chief photo editor) and he was like, “Dude, he sent me a letter back, telling me what was wrong.” So I did the same thing. Then the phone number of Transworld, I had from talking to Masekela, and it was in the magazine. So I would just call and be like, is Grant Brittain there?

And I would just ask him things. That’s why I was a Transworld person. Because Slap, there was no phone number [in the magazine]. I would’ve called them for sure. But Transworld there was a phone number, so I could get a hold of them. I was just sending photos. [And Grant] would critique them. That’s one big thing that I always say, advice-wise: As a photographer, we all think our photos are the greatest. Right? We’re like, “Our photos are the best,” [but they’re often not].

And I remember Grant being like—I was shooting with a [third-party] 28mm lens, just kind of [a bad lens]—I remember Grant being like, “Yo, put your slide on the light table and look at it next to a magazine, and tell me if your photos look as good as those of the magazine.” And when I did that and I was like, “No, my photos are terrible.” It pushed me to go, “How do I make my photo look like those in the magazine?” And that’s obviously photography. If you want your photo to look like Anton Corbijn’s, look at his picture and figure it out. Which is at the same time bad advice, because then I start emulating Spike Jones and all these [other famous photographers] and I didn’t really give myself my own style until a little bit later in life.

You seem to have a knack for photographing subjects that move quickly.

I think the amazing thing about action is, that it’s literally one millisecond that will never happen again. In portraiture, you can get five frames of the same, exact expression. But [with action] you will never get the exact same moment. I think it’s also the self-deprecation of knowing when you [screwed] up and being like, “I’m going to get it right.” And still, you don’t. But chasing it, it’s like chasing a high, I guess.

It’s fun to look through your portrait portfolio and to see all these really big names that you’ve worked with. Your subjects always look so calm and at ease, it’s quite the contrast to your action-oriented shots.

Photography is a social skill. It’s 75% social skills, it’s 25% knowing how to use a camera. My whole thing is, my portraiture, I don’t even think it’s that… I think it’s good, but a David LaChappelle or someone who gets these people to get all crazy, I think that’s amazing. But I don’t want to force people to not be who they are. So when I approach a portrait, I go, “Hey, I want you to be yourself. Do you like smiling?” And some people are like, “Yeah.” I’m like, “Let’s get that. If you don’t, just stand there.” I shoot really fast because most people don’t like their pictures being taken.

I want people to have a good time. So it’s really making sure the vibe’s good, picking up on signals if they’re not into it, shoot it quick and be out, you know?

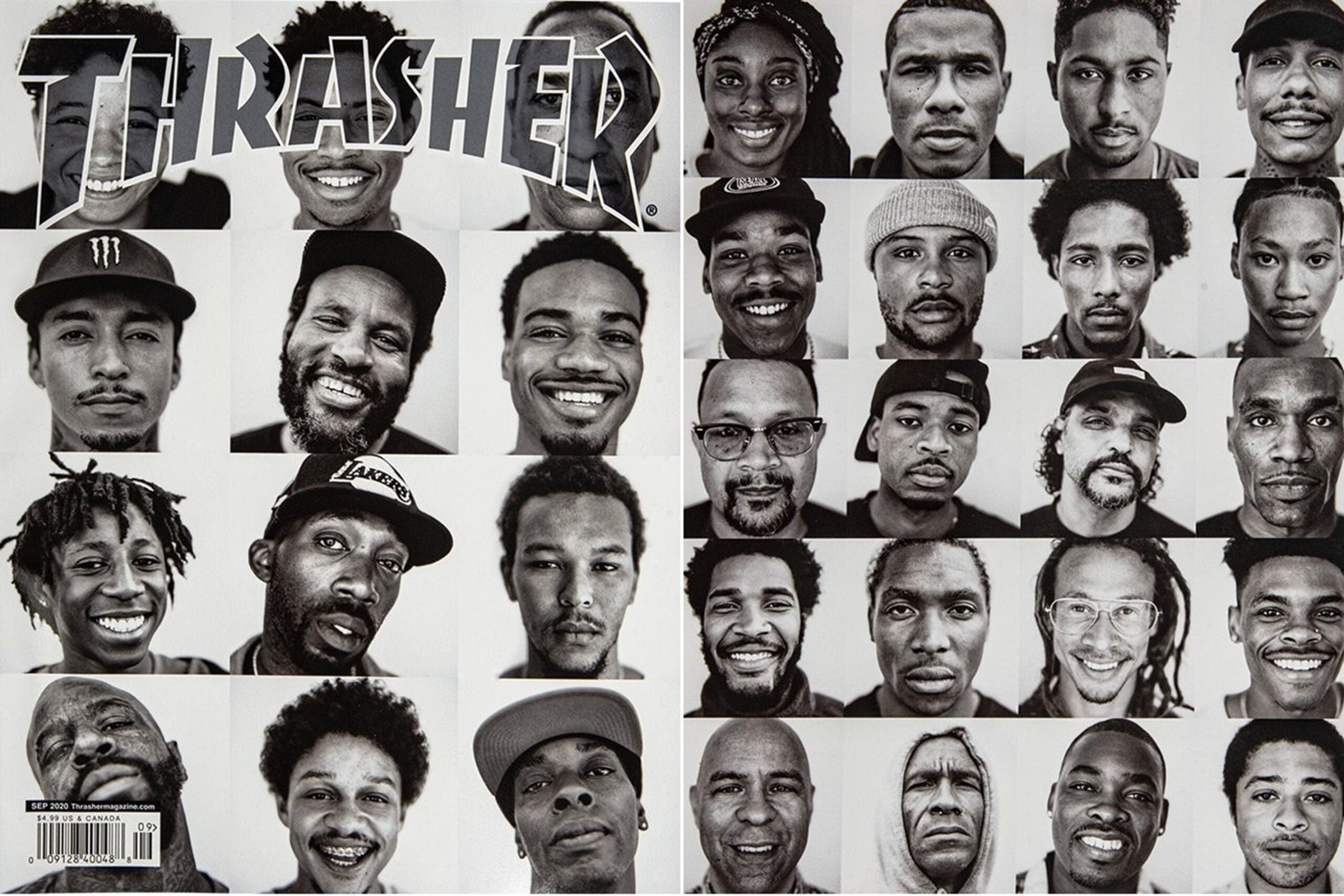

Speaking of portraits, your September 2020 Thrasher cover showcasing portraits of legendary Black skateboarders, both past and present, is super iconic. Can you just tell me a little bit about how that came to be, conceptually?

Everyone talks about recognizing the impact of Black culture on skateboarding. Everyone knows it. But it was just a perfect time for the world to kind of stop and recognize the impact of the Black community all over the place. And they (Thrasher) were like, “Yo, we want you to do what you want to do.” So it was an amazing opportunity to be able to go, “Hey, this is what I think.” There’s not just one, there are so many Black skaters that have changed skateboarding. It was great to just be able to hand-pick it. They were like, “Do you.” There was no question asked. It was more just hard to narrow it down to a [specific] number.

So you came up with the idea, did you also have a say in the final arrangement?

Yeah, totally. They were like, “What do you think?” Working for Thrasher was really amazing. They really respect my opinion as much as I totally respect theirs. So yeah, they were 100% like, “Exactly. Do you. Let’s see your vision.”

Speaking of magazines, is there a favorite cover you’ve shot?

I have 10 (Thrasher) covers now. And that’s it, I’m done. But really, Tyshawn Jones is like a little brother to me. Obviously, my favorite cover would probably be… not probably. My favorite cover is obviously the Black skaters’ portraits. But Tyshawn, I get so proud to see this kid I’ve known since he was just a little kid at 14, wanting some Emericas (skateboard shoes), to become who he’s become.

I’m still chasing my favorite cover. That’s the thing. I don’t see the perfect thing. I see what I did wrong and what I can do better when I see my photos.

What it was like to cover the Olympics both as a photographer, and also someone who grew up with skateboarding?

It was a huge honor. I’ve shot Kobe Bryant every time he’s won a championship. I’ve been there when he lost one. So I’ve seen these glorious moments on the world stage. And skateboarding’s never really been on that as far as a contest. And then to be there for that moment, it was amazing. It was just really cool.

I know you recently started working with Canon as an Explorer of Light, what’s that been like?

It’s a dream come true to be able to be recognized for my photography, from a camera company, versus shoe companies or board companies or whatever. [Some companies] are like, “We want to do this with you. We want to do that with you” and I’m very flattered and honored to do that stuff. But a camera company—and especially as a skateboarder, to be Black and be able to work with a brand that you never thought was attainable—it’s unbelievable. The fact that I can inspire other photographers the same way, is just great. And to be able to go to the Olympics and shoot with the EOS R3 that no one [had at the time]—to shoot with these cameras that aren’t even out, it’s unbelievable.

And to be able to talk to the Canon team the [at the summer Olympics] and them wanting to know my input on what can make the camera better, and “what do I want and what do I need?” It’s just great, all the Canon resources.

So, now that Canon’s listening, are there any lenses on your wish list that you’re hoping to see made?

If I could phantomly invent a lens? Well, that would be up 14-200mm f/2.0 (laughs). [Canon] just keeps blowing me away. The 14-35mm has been such a game-changer for me. Unbelievable game-changer. It’s one of the most fun lenses I’ve had in a long time. And like I said, the 50mm f/1.2 changed my whole look. That’s what I shot that Thrasher portrait cover with.

And eye detection, with 50mm f/1.2 and eye detection, you’re good to go. It’s just wider, more light. I’m really into more light. I’m really into f/1.2. I love that shallow depth of feel you get.

I was going to ask, were most of those portraits shot at f/1.2, or were they stopped down a little bit?

Everything was f/1.2.

Do you have any tips for young photographers today? How can they get their feet in the door?

Pay attention to what you can do to improve your photography. Pay attention to those who are good at it and what they’re doing. And just love what you do. If photography is something that you don’t really love, it’s going to be a tough thing. I know there are people who just want to be a photographer for the glory and it works for them. But for me, it’s just [about] having a passion for it and just enjoying it—life’s too short to not do what you want to do.

Check out more of Atiba Jefferson’s work here.

The post Skateboard photographer Atiba Jefferson on getting your foot in the door appeared first on Popular Photography.