![]()

During the long pandemic quarantine, I bought a laser cutter the size of a small Volkswagen to cut ventilator prototype parts, Brooklyn Film Camera Polaroid scan trays, and a number of other photographic equipment parts. I bought the largest cutter that I could fit in my shop, because I had been dreaming of the 20×24 Polaroid and Afghan box cameras since I was about 16 years old.

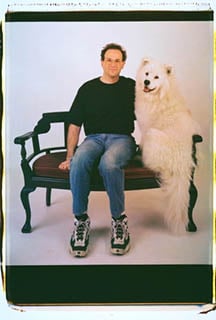

I became fascinated with 20×24″ Polaroids when I first saw a profile photo from the creator of Photo.net, Phillip Greenspun — a thumbnail of himself and a big fluffy white dog on a white backdrop:

That photo was taken by none other than the great, late Elsa Dorfman, and I remember internet sleuthing everything I could about her work — a more difficult job in 1999 than it is today.

That led me to learn about the 20×24″ Polaroid cameras and their history, which really captured my imagination, and stuck with me for a long time.

The original seven 20×24″ Polaroid cameras were built in the late ’70s and early 80’s more or less as an advertising campaign for Polaroid’s smaller format consumer films and cameras. The camera was lent or rented to famous photographers and artists, like Andy Warhol, Mary Ellen Mark, Chuck Close, Elsa Dorfman, William Wegman, and many more, who made some of the most iconic images of the last half-century with them.

The Polaroid corporation has long since changed hands and ended production of peel-apart films, including the 20×24″ media, and what very little media is left doesn’t look nearly as good as it did when it was fresh. For now, at least, the 20×24″ Polaroids are an incredibly beautiful, but dead format. It is one of my regrets that I never had my portrait taken by Elsa Dorfman, and now I never will.

I have also been interested in Afghan box cameras (AKA kamra-e-faoree), or Cuban Polaroids, Lambe Lambe, Camera Minutera, or more generally Lab Cameras since I was a teenager and saw a Popular Photography article about the Cuban Polaroid street photographers of Havana.

I was taken by the idea, because it was a relatively fast process that you could do in front of your subjects, and because it was relatively inexpensive and at 15 or 16, I was a part-time professional babysitter and IKEA furniture assembler. I never actually built a proper Cuban Polaroid back then, but I did manage to duct tape a changing bag to a hole in a large Rubbermaid tub that my friend Ryan Muir and I used to process 8×10 paper negatives in blacked-out bathrooms all over New York City when we were kids.

I always loved shooting 8×10 paper negatives but had no professional reason to do so, and so over the last 20 years, Ryan and I have shot two weekend-long projects with the camera and that’s it. Ryan and I had a great time and so did our subjects, and it has been something that we’d both love to find a reason to do again.

![]()

![]()

Years went by.

I moved to the desert, became a professional camera builder, and more or less stopped taking pictures for fun, save for a few vacations. I met Joe Van Cleave, camera builder and YouTube superstar a few years ago and we became fast friends. We hang out just about every Tuesday and work on building cameras and whatever projects strike us.

I usually use Tuesdays to work on short and simple projects, as a bit of a palette cleanser from whatever I am working on that week. I have to be very careful that Joe doesn’t spark my interest in something that will eat 6 months of my time because I can’t think of anything else. I have had to shelve “Joe projects” more than a handful of times because I just can’t afford to spend months building a pen plotting typewriter, or a laser-cut grandfather clock, 3D printed abacus beads, or mechanical calculators. Sometimes Joe does capture my full attention, and that’s exactly what happened when we started tinkering with direct positive reversal prints.

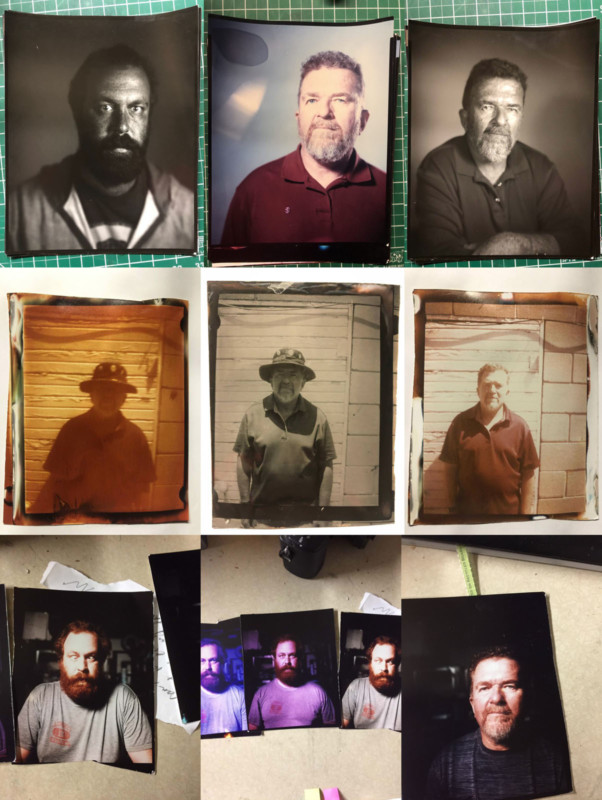

Joe had built an Afghan box camera years before we met and had done some semi-successful experiments with a reversal process that could produce positive black and white prints on paper, rather than the paper negatives that I was used to working with, and that street photographers all over the world would rephotograph on an easel to make a positive print. Joe and I spent years working on first black and white direct positive prints, and once we had mastered that process, moved on to color direct positives using RA4 color printing paper.

I have hundreds of prints of Joe, with different color balances, exposures, stains, light leaks, and every manner of imperfection made during our years of tests. I like to call this the “Infinite Joes” series. We never really thought of these pictures as art, they were just test photos of joe standing in one or two places, with about the same expression and different clothes around my shop and backyard, but they kind of grew into a series over the years, and I think I’ll probably make something from them one day.

Because Polaroid peel-apart media has long since gone out of production, Joe and I thought that the color reversal process could be a reasonable and accessible replacement for the original 20×24″ Polaroids — perhaps in the form of an Afghan box camera.

Photography on a Much Large Scale

Building a 4×5 or even 5×7 Afghan box camera is a whole different type of project than building one for 8×10 or larger.

The scale of the processing space just increases past the scale of something that a human can easily manipulate. Paper becomes large and unwieldy, tanks require more heavy and spillable chemistry, and the camera itself quickly becomes too large and heavy to move comfortably. Thinking only about 8×10, I might have tried a number of more classical designs and pushed the limits of lightweight materials, but I was already drawing connections between reversal prints, Cuban Polaroids, and the original Polaroid cameras in my mind, and 20×24″ was a natural goal to consider.

A back of the napkin calculation of the weight of JUST THE CHEMISTRY inside an initial 20×24″ Afghan box camera design was between 75 and 120 pounds (34-54kg). That sent me back to the drawing board. How could I process reversal prints instantly, at a large scale, without having the camera be the size of a van? It took a few days of sketching and staring off into space before I struck on the idea of a self-developing film back — a large format film holder, which is a bit deeper than standard but otherwise dimensionally the same, that had a light baffle so that I could pour chemistry in and out of the holder and process the photo immediately without a darkroom.

I built one single 8×10 prototype that Joe and I used successfully for about 50 or 60 pictures. The original design worked very well but was a pain to produce and wasn’t as durable as I would have liked. It had an awkward yellow angled screw-on funnel on the top that looked like the antenna on a Snork. Joe and I put the project on the backburner during the beginning of the 2020 lockdown.

During the pandemic, I did a bunch of work on an open-source simple ventilator that could be built almost anywhere (openventilator.io) and had to cut enough wood and acrylic parts for work that it became worth it to buy a giant laser cutter and dedicate a quarter of my shop to it.

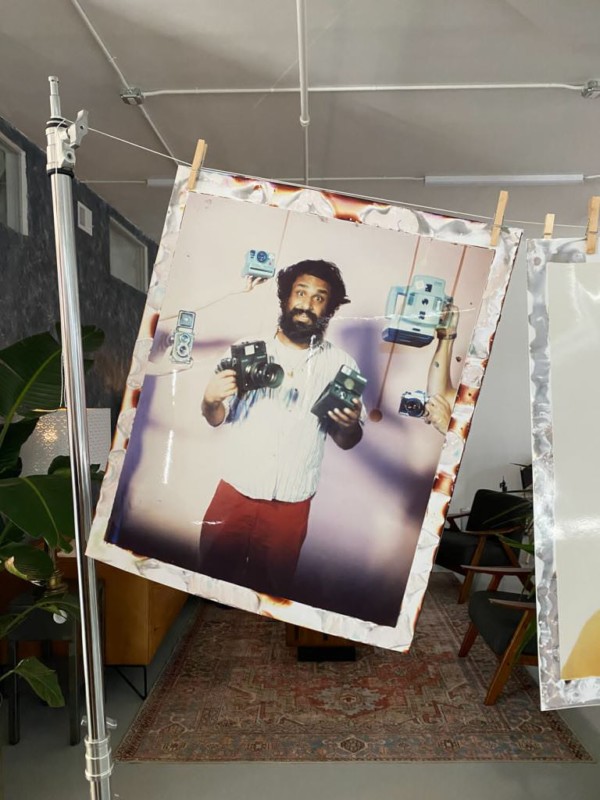

Joe and I had both made YouTube videos about the black and white and color reversal processes early in our investigations, and while we did little to no work on it during the pandemic, lots of people picked it up. There were more YouTube videos and message board threads and Facebook groups created around the reversal processes we were using. Inadvertently, those videos created a much larger market for something like a self-developing film holder, which makes the process much easier and infinitely more portable. When the lockdown ended and my schedule freed up a bit, I spent about 5 or 6 months finalizing the 4×5 and 8×10 self-developing back designs, making a first production run of them, and then designing and building a 20×24 version and a camera to go with it (the thought being to use it as advertising in a similar way to the original 20×24’s built by the Polaroid Corporation).

I was planning on taking the camera up the West Coast, shooting some portraits, and maybe giving some workshops along the way to help pay for the trip and just to get the reversal processes and self-developing backs in front of people who were interested.

I got an invite from Kyle at Brooklyn Film Camera to be the opening act in September 2020 at his new photo studio in Brooklyn, Wyckoff Windows. Kyle is a friend and has always been really fun and easy to work with, so I put the West Coast trip on hold and headed to New York with a cargo van and about one ton of equipment.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

We sold out two weekends of portraits and workshops and then did another sold-out weekend as an encore. I was amazed at the outpouring of the community. I got to meet a photographic idol of mine who showed up for a portrait on a Sunday morning, I had two workshop attendees who had worked and currently works for Mary Ellen Mark’s studio.

One of them had a portrait taken on an original 20×24 Polaroid by Mary Ellen Mark from years ago. I got to meet Allen Murabayashi, who founded Photoshelter and changed the landscape of the industry. I met Carla Rodriguez, who flew in from Minnesota to take a workshop, and whom I had been following on Instagram since starting this project, to see how working wet plate photographers run their business. I met so many amazing people who were really into the types of things that I thought that only Joe and I were interested in, in my garage in Albuquerque.

I learned a few things about the camera too, about how long it takes to set up and get dialed in, and how many people it really takes to keep the camera running relatively quickly, about how much chemistry you can go through in a day, and really got a feel for the process that I never had the opportunity to back in Albuquerque.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

I am still planning on releasing the self-developing backs as a product, but that will eat a few months of full-time work when I do.

Now that I’ve really got the hang of the camera, I’d really love to shoot some more commercial and advertising work with it. I’d also love to rent the camera out to some of the famous iconic photographers of our time and help them create images with the camera too. For now, I am going to go to Los Angeles to use the camera in a studio with lots of help and interesting subjects, and people interested in the process.

P.S. I’ve launched a a Kickstarter campaign to bring the camera to Los Angeles because of the expense of renting a studio and hiring help, buying bulk chemistry and paper, driving a ton of gear across the country…you get the idea. Kickstarter is helpful because I can ask the community who wants a portrait, a workshop slot, a rental day, or to come to an open studio session, and gauge that interest before committing to renting a space. If there are enough people to make it feasible to bring the camera to LA, Kickstarter will charge everyone and I’ll come, but if there isn’t enough interest, nobody gets charged and I will just happily return to my humble life as a backyard camera maker in the desert.

About the author: Ethan Moses is the photographer and camera maker behind CAMERADACTYL Cameras. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. You can find more of Moses’s work and connect with him on his Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.