We revisit an interview with the visual activist ahead of their first major survey in Germany opening at Gropius Bau

Everything about Zanele Muholi’s art is political. The aesthetic – the colours, the composition, the light – is political. The individuals depicted, elevated by and enveloped in those aesthetics, are also political. Being political may not have been what Muholi, their photographs and their subjects chose, yet historical and contemporary discrimination, which wrote and continues to write them out of history has rendered them so, forcing them to reclaim their narrative from those who have co-opted and denied it. In creating a visual history of the Black LGBTQIA+ community through their work, Muholi, and the individuals they photograph, push back against this repression, carving out space for themselves and their wider community in visual culture and beyond.

“I consider myself a visual activist first and foremost because my work has a political agenda,” writes Muholi, the Black, Queer, non-binary visual activist, who takes the pronouns they, them and their. “What is important to me is how my work challenges and contributes to society and the place of Black LGBTQIA+ people within it,” they continue, responding over email in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic. Before the lockdown regulations came into effect, Muholi was due to open a solo exhibition and first UK mid-career survey at Tate Modern, London. This was postponed before finally going ahead earlier this year, and now it reopens at the Gropius Bau in Berlin as the artist’s first major survey in Germany. The show spans work from the photographer’s entire oeuvre – at its centre, it unpacks what it means to be a visual activist and the repressive social and political context from which this position and their practice have emerged.

Born in 1972 in the township of Umlazi, Muholi grew up at the height of apartheid — a system of racial segregation in South Africa, formally implemented by the white minority regime in 1948. The government justified apartheid as a means to maintain peace and stability. In reality, it represented the continuation of the country’s colonisation by Dutch and British powers at the start of the 17th century, and the subsequent discrimination and repression of the Black population. The government enforced countless racially-motivated, segregationist policies and laws to repress Black communities, such as the establishment of Bantustans – 10 territories where the majority of the Black population was moved and further separated according to a state-assigned ethnic group. There were also pass laws, which required Black people to present identity documents detailing both race and gender when moving outside of their designated area. As a Black domestic worker, serving a white family in an urban area for more than 40 years, Muholi’s mother was subject to this legislation, which fractured families such as Muholi’s own, who could no longer move together freely.

In 1994, internal unrest and external pressure from the international community resulted in the formation of a new constitution and the election of a bi-racial coalition government, with Nelson Mandela as President. This marked the official end of apartheid. The government began work to address the social and economic legacy of apartheid: poverty, inequality, education and infrastructure. Even the sphere of sexuality was subject to the government’s compulsion to control during the apartheid era, both in relation to race and sexual orientation. The Morality Act of 1957, for instance, criminalised interracial relationships and homosexuality. In 1996, however, the post-apartheid constitution became the first in the world to outlaw discrimination based on sexual orientation. A decade later, South Africa became the fifth country globally to legalise same-sex marriage.

“I picked up the camera because there were no images of us that spoke to me at the time when I needed them the most. I had to produce a positive visual narrative of my community and create a new dialogue with images”

Despite radical and progressive changes at a legislative level, discrimination against Blacks and the LGBTQIA+ community, especially its Black lesbian, trans and intersex members, continued throughout the country with a significant gulf between the commitment of the law and lived reality. Harassment, aggression and often fatal violence against the LGBTQIA+ community remains widespread; ‘corrective rape’, a horrific hate crime in which the victim is raped on the basis of their perceived gender or sexual orientation, is pervasive.

The struggle against systematic racism and discrimination against the LGBTQIA+ community share a complicated past, which extends into the present. LGBTQ activist groups began to form during apartheid, but the disconnect between racial tensions and sexual discrimination fractured the concurrent struggles for Black and LGBTQIA+ rights. It was not until the 1980s that multiracial lesbian and gay activist organisations emerged. Today, the enduring impact of apartheid, both economically and socially, and ongoing sexual discrimination, continue to impact the lives of Black LGBTQIA+ South Africans particularly. Ultimately, “the legacy of racial segregation continues to bear its mark on the lived realities of LGBTQI individuals,” reads a 2015 report on the conditions for LGBTI individuals in South Africa, published by the Astraea Lesbian Foundation for Justice.

Muholi studied on the Advanced Photography course at the Market Photo Workshop in Newton, Johannesburg in 2003, followed by an MA in Documentary Media at Ryerson University, Toronto, in 2009. When they began taking photos, there was a critical lack of scholarship, including visual representations, of the LGBTQIA+ community and particularly its Black members in South Africa. But Muholi was not interested in waiting to become someone else’s subject, regardless of how well-intentioned their work and attempts at representation may have been. Instead, they worked, and continue to work, to reclaim, write and re-write the troubled and repressed history of their community, for which Muholi has become an activist, archivist and witness. “Muholi’s work entered into a void of representation when it came to presenting positive imagery of Black Queer lives in South Africa,” explains Sarah Allen, the former assistant curator of International Art and co-curator of the exhibition at Tate Modern, alongside Dr Yasufumi Nakamori, senior curator of International Art (Photography). “Muholi is responding to a lack of visual evidence of their life and their reality in post-apartheid South Africa. They are creating an archive and writing that history themself.”

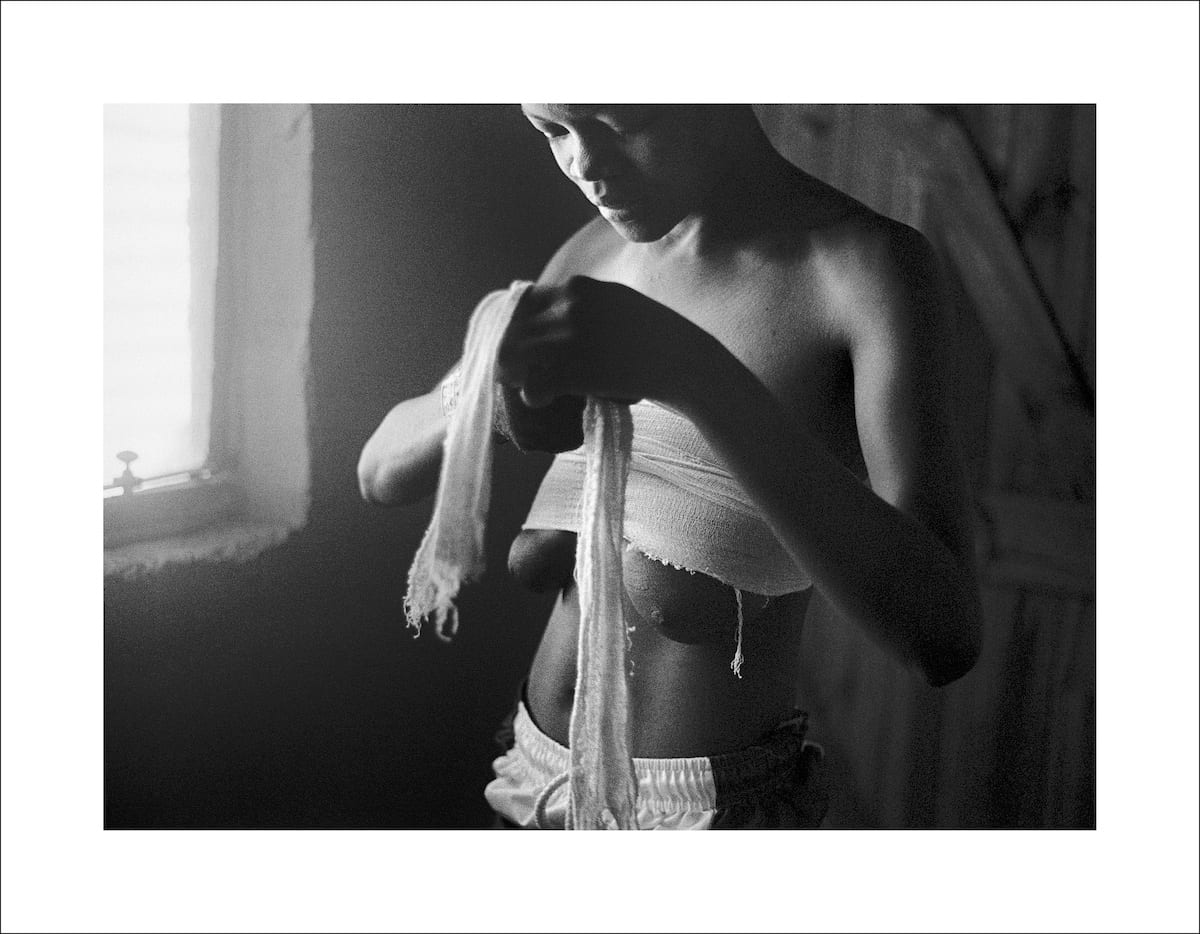

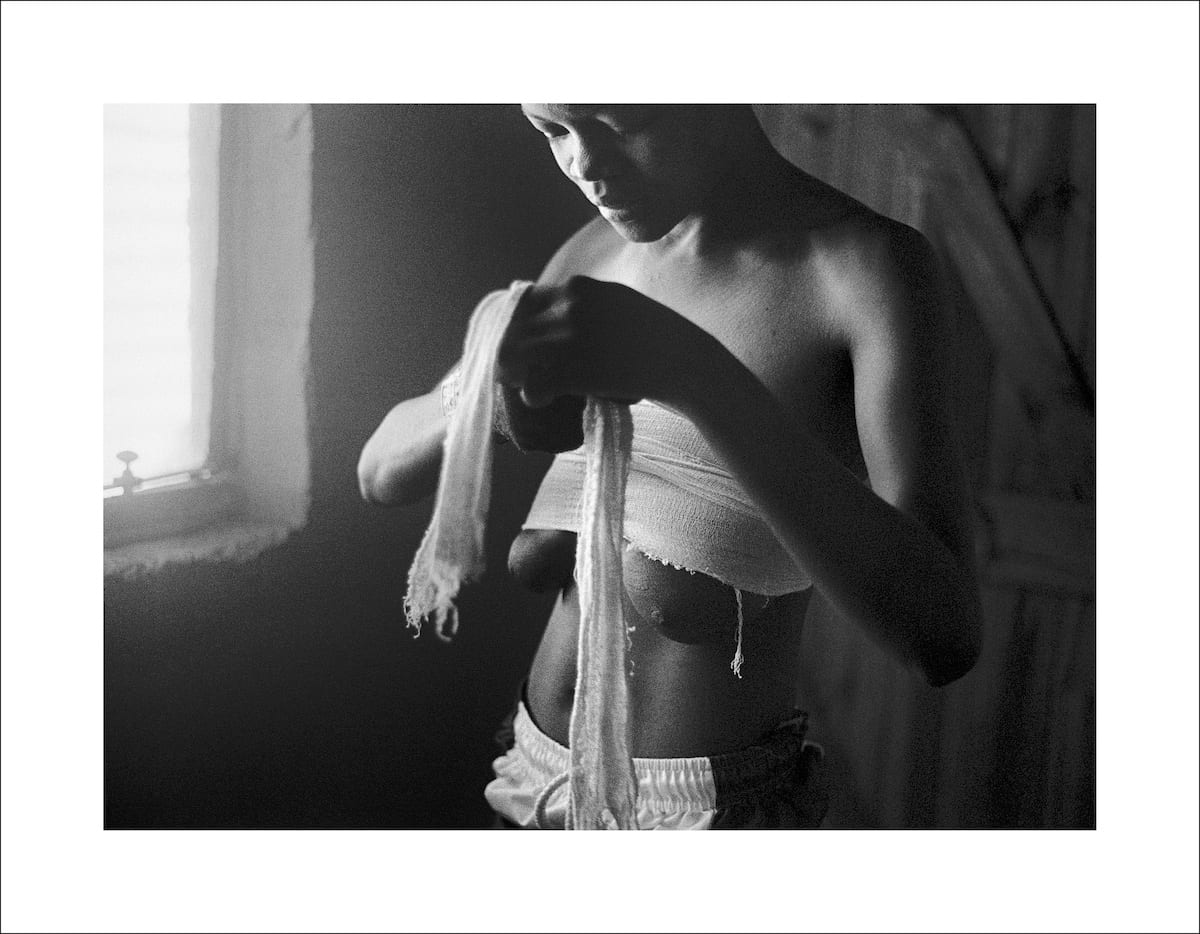

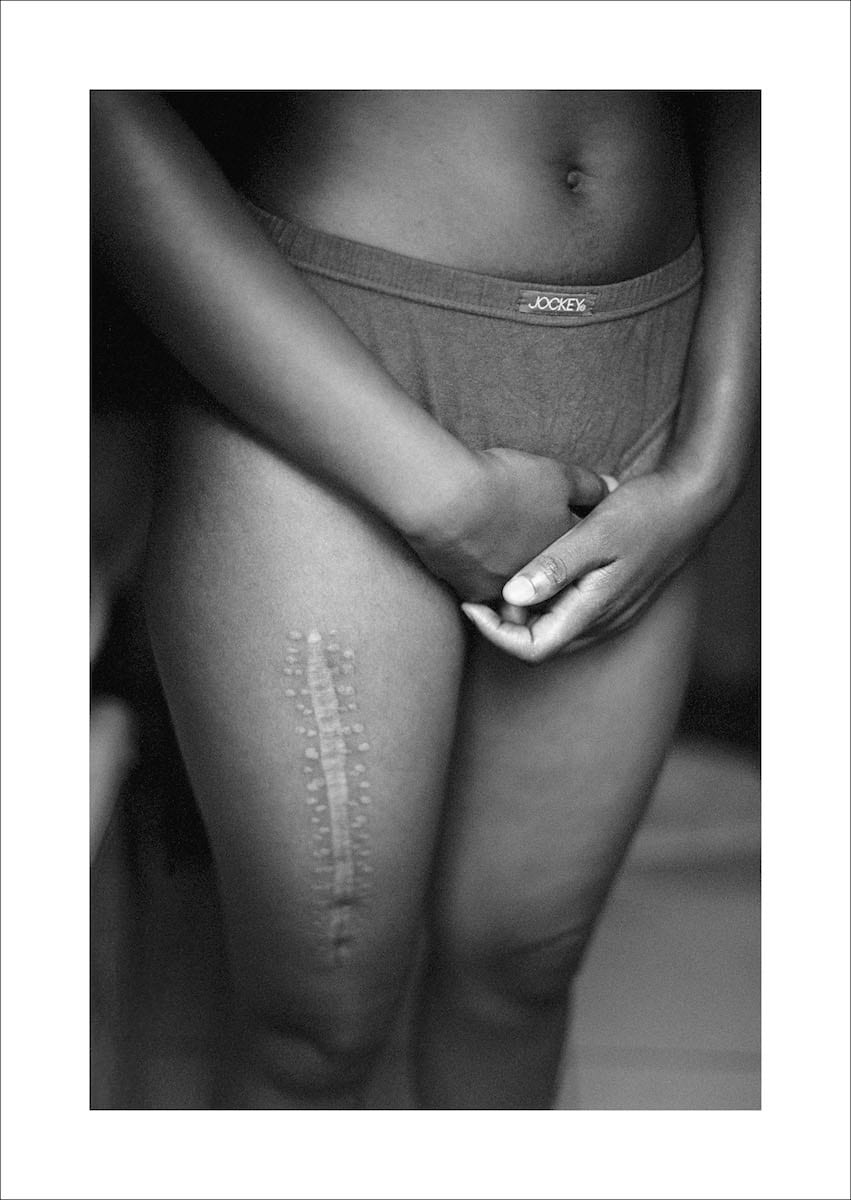

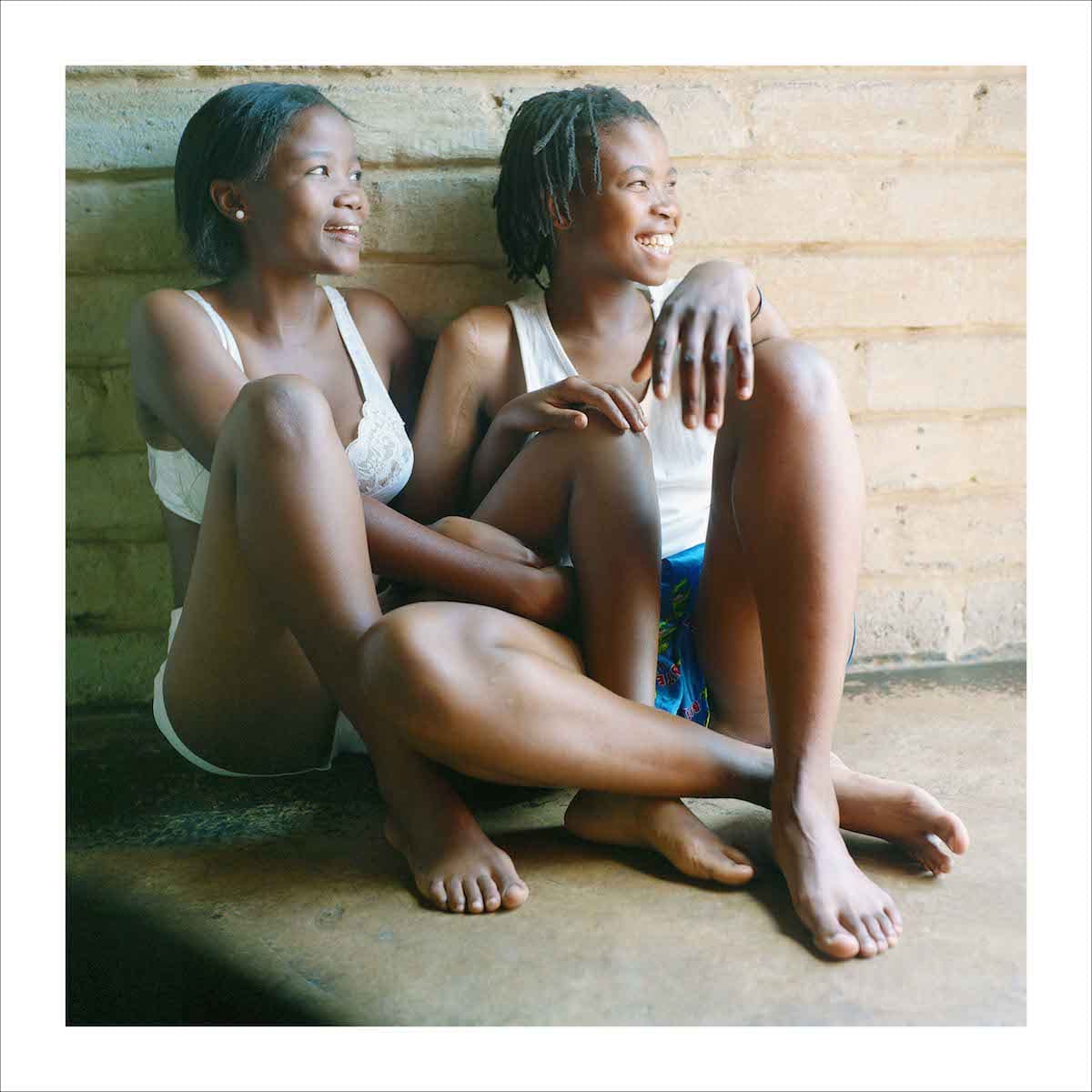

Dichotomies run through Muholi’s visual history: tensions that reflect the LGBTQIA+ community’s difficult past and present, in South Africa and beyond it. These dichotomies – between the individual and collective, celebration and mourning, joy and pain, power and vulnerability – appear to various degrees and in different incarnations throughout their many projects. In Only Half the Picture (2002-2006), which garnered Muholi critical acclaim when it was exhibited at their first solo exhibition Visual Sexuality: Only Half the Picture, at the Johannesburg Art Gallery in 2004, the artist presents anonymous images of survivors of rape and hate crimes. Love and intimacy appear alongside trauma; beauty and suffering coexist. Menstrual blood flows across a sanitary towel, a Black woman straps on a white dildo enveloped in a condom, hazy silhouettes reveal a couple making love, scars and slashes maim bare skin. “The series is more about intimacy, privacy and body politics within our community, rather than about specific individuals,” writes Muholi. The images exude both sensuality and pain. Muholi’s representations are visceral, uncensored windows into the pleasure, intimacy and suffering experienced by their community. The series also works to break down ignorance towards lesbians among the Black African community and beyond it: the abundance of menstrual blood, for instance, challenges the widely held misperception that butch women do not menstruate.

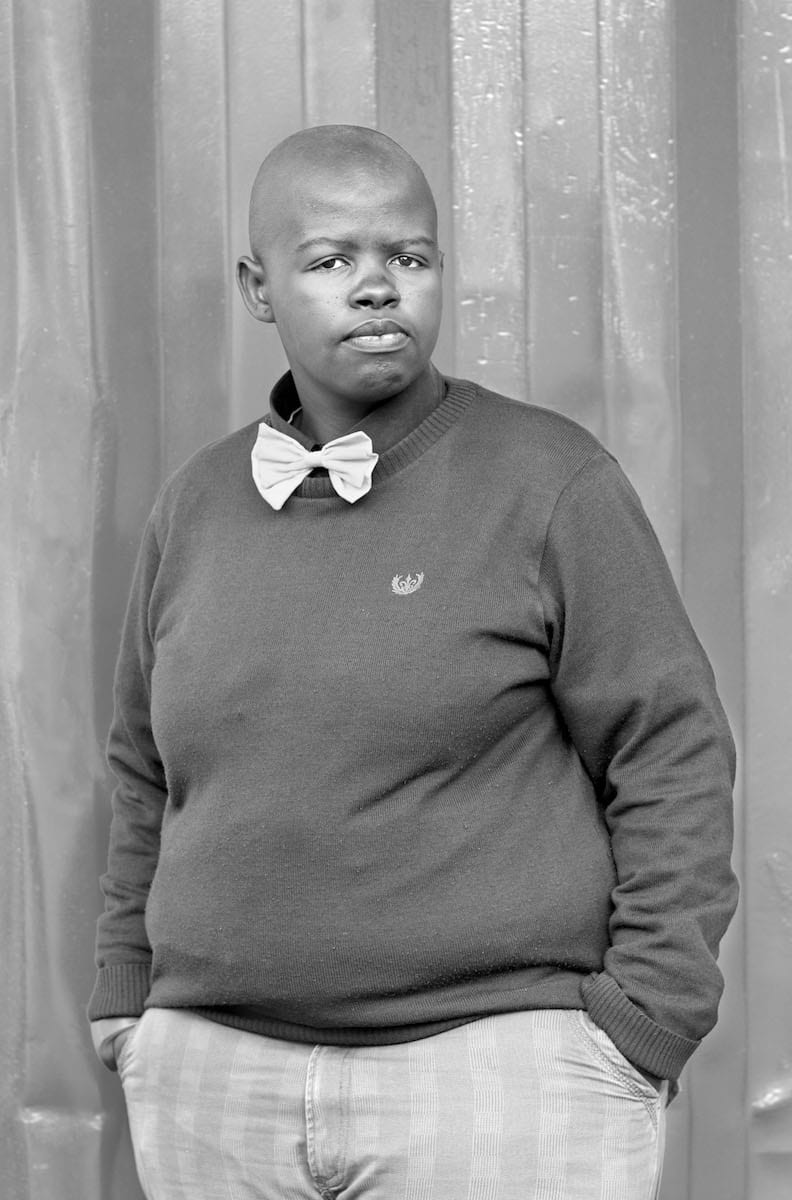

In the ongoing project Faces and Phases (begun in 2006), which came next, identity and individuality are central. Participants look directly at the camera; they hold our gaze. Muholi dedicated the series, which has been exhibited in multiple exhibitions worldwide such as the 55th Venice Biennale and Documenta 13, to Busisiwe Sigasa – a friend, poet and activist who died aged 25, eight months after the artist photographed her for the project. She died from AIDs-related complications, which she contracted after becoming a victim of ‘corrective’ rape. Today, Faces and Phases comprises hundreds of portraits of Black lesbians, transgender people and gender non-conforming individuals from South Africa and beyond. The participant’s name, the place where the photograph was taken and, in some cases, individual testimonies detailing the injustices they have suffered, accompany each image, providing context and affirming the place of those depicted, in history.

The project recognises its participants as individuals, who express themselves via their postures, their dress, and their expressions. It also acknowledges them as a collective: an evolving visual archive, often exhibited in tight grids, of a community that remains gravely underrepresented. ‘Faces’ refers to the people pictured and Muholi’s encounters and relationships with them, while ‘Phases’ signifies the transition from one stage of sexuality or gender expression and experience, to another. “Muholi’s elixir is the hope that people can look at the faces of those depicted and not feel alone should they also have faced racism, homophobia, transphobia or other forms of prejudice and exclusion,” says Allen. “They have said that their work is ‘not for show or play’. It performs a serious function in terms of giving the people depicted a sense of pride, a sense of worthiness. Muholi’s participants are not presented as types, rather each has their own specific stories to tell. The hope is that this, in turn, breeds mutual understanding and respect.”

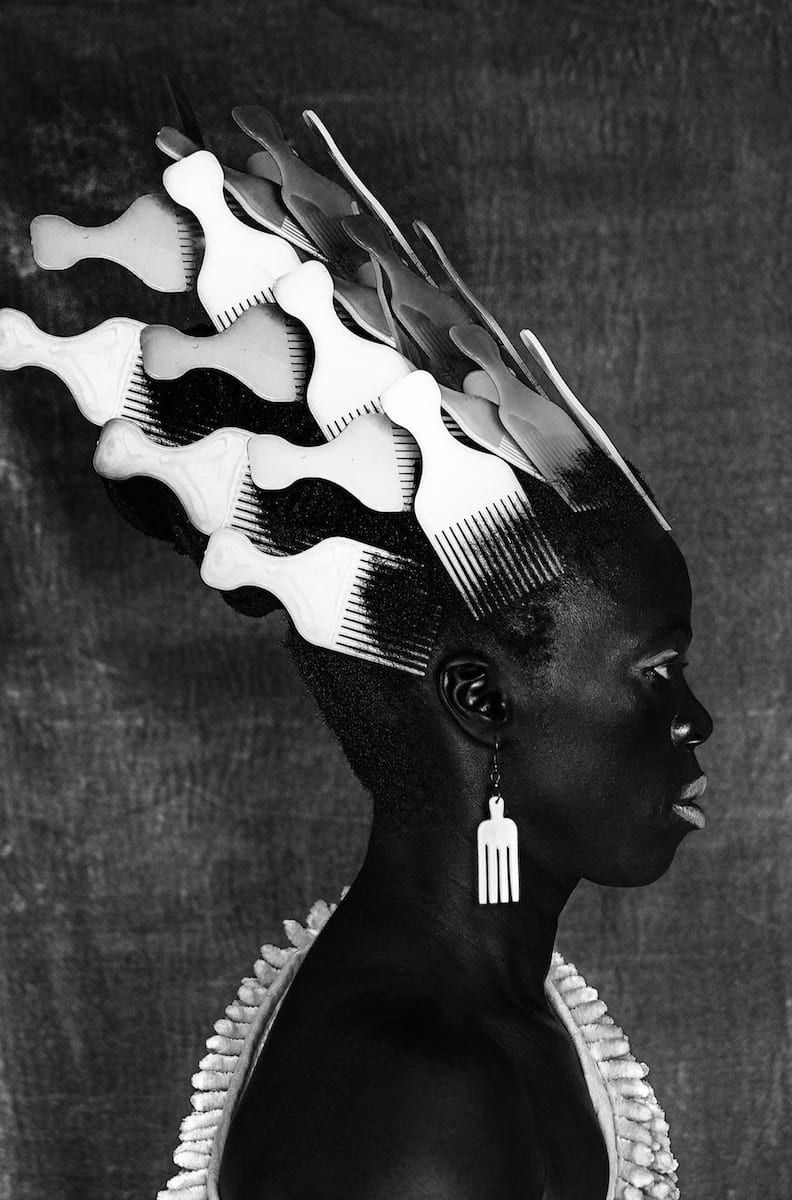

In 2012, Muholi began work on the ongoing project Somnyama Ngonyama (Zulu for ‘Hail the Dark Lioness’), which was exhibited at Autograph in 2017 at the artist’s first solo exhibition in London. Now Muholi takes centre stage, staring boldly out of the frame; confronting our gaze. “I use my own body and face because the work is meant to be confrontational, both personal and political at the same time,” they write. “The project addresses my experiences in our society head-on: things that are painful. I would not expect anyone else to carry that with me. I had to do it myself.”

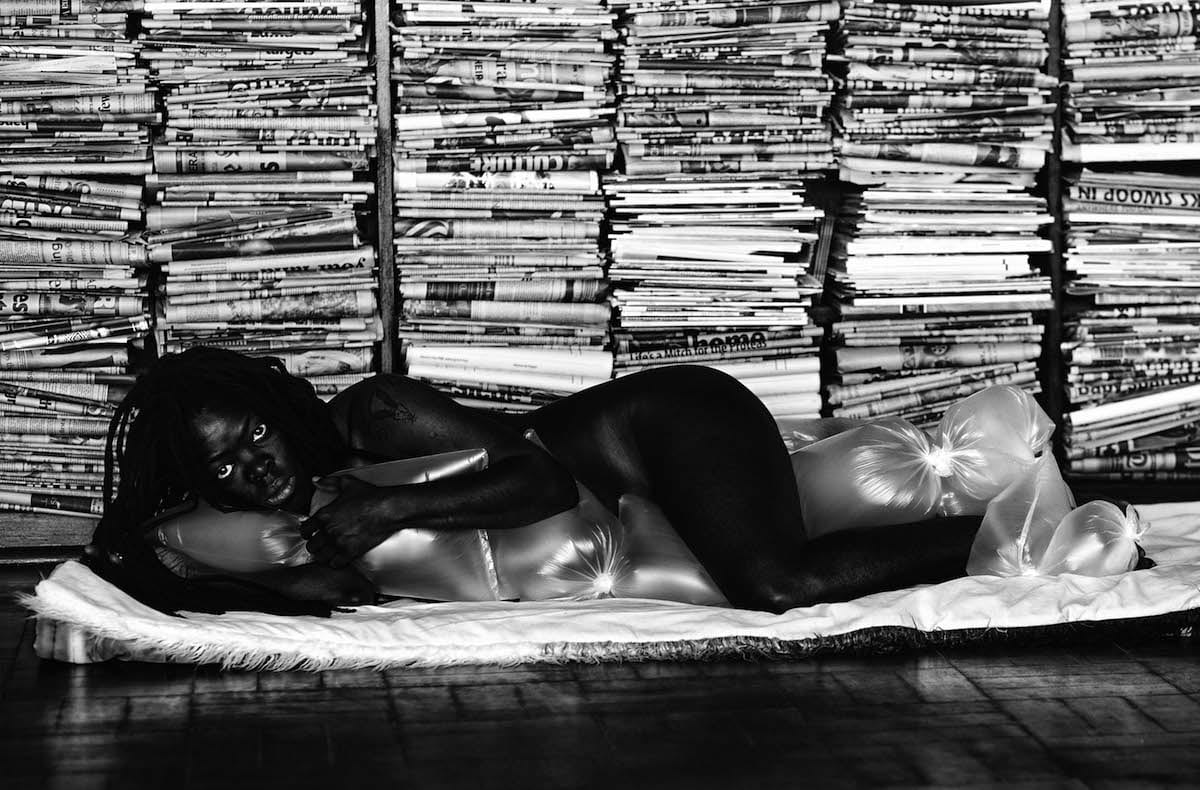

In each photograph, Muholi confronts issues and experiences that have affected them, and that affect Black and Black LGBTQIA+ individuals on a much wider scale, in the present day and throughout history. The ongoing series of portraits, which currently comprises around 200 works, is unspeakably powerful. Muholi increases the contrast of their images to render their skin pitch black and employs accessories, mostly everyday items, to further construct the narrative of each photograph.

“[The work] is a body of self-portraits that deal with politics of representation, race and Blackness,” continues Muholi. In one image, Dalisu, coils of woollen string consume the artist, suffocating and constricting them. Muholi made the photograph after being questioned by a hotel manager before being allowed to check into a room, which had already been booked and paid for. “I just felt so tangled and confined, confused and angry,” they told The Guardian in 2017. In another, Muholi, wearing a miner’s hat and goggles, stares out with eyes wide and unsettled. The image remembers the 2012 Marikana massacre in South Africa, during which 112 striking miners were shot down by police, of which 34 lost their lives. Other photographs address more internal struggles. In one image, Muholi’s naked body curls around inflated plastic bags. These symbolise the large fibroids that were removed from their womb by an operation they did not know if they would survive.

“My images are portraits, so if my work is being exhibited, someone else’s existence is also being affirmed. What matters is having a dialogue — with people, with institutions and with history. It’s a collective project of reclaiming space”

Muholi’s work unquestionably empowers its participants, yet it also renders its subjects vulnerable, opening them up to the scrutiny of viewers and amplifying their identity to those who could potentially abuse it. “To face the camera is to open a conversation, to make yourself both vulnerable and powerful at once,” writes the artist. It is significant then that Muholi’s own presence is constant throughout their work and that their visual activism is also accompanied by other forms of advocacy. In 2002, Muholi co-founded the Forum for the Empowerment of Women (FEW), a Black lesbian feminist organisation that engages in advocacy, education and action. Then, in 2009, they founded Inkanyiso, a platform they conceptualised three years earlier, which emerged in response to the lack of visual histories and skills training created by and for the LGBTQIA+ community. “Queer Activism = Queer Media,” reads the platform’s About page, which showcases articles, reports, and photographs, produced by different contributors.

“Muholi speaks about how their audience is anyone and everyone. Their work is not just for the Black Queer individual, it is also for the viewer who may never have been presented with a nuanced image of a Black Queer individual,” says Allen. “Their form of visual activism is designed to open minds and educate.” The importance of representation and recognition resonates with that of other activist movements worldwide. In a recently republished article for The New York Times, essayist and playwright, Claudia Rankine, writes “with Black Lives Matter, a more internalised change is being asked for: recognition … The hope is that recognition will break momentum that laws haven’t altered.” Demanding recognition for the Black LGBTQIA+ community in South Africa and beyond is a central facet of Muholi’s approach. When a community is able to represent themselves and take ownership over that representation, it becomes harder to write them out. Representation contributes to recognition, and hopefully understanding, awareness and change; with recognition it becomes less easy for others to condone or ignore the injustices of abuse, inequality and discrimination that Rankine alludes to.

In the following interview, Muholi reflects on their work in their own words and discusses the significance of having a mid-career survey at Tate Modern, affirming their place in history and the world, in the context of this institution, this moment, and beyond. They discuss what that means for them as a Black LGBTQIA+ artist representing their community.

Could you speak about the very beginnings of your career as a photographer, including your time at the Market Photo Workshop [founded in 1989 by South African photographer David Goldblatt to provide arts education during apartheid] in Johannesburg, and Ryerson University in Toronto? How did growing up during apartheid impact your practice and what turned you on to photography and the possibility of representing yourself and Black Queer identity? Who and what has influenced you?

Market Photo Workshop was part of my formative period as a photographer and marked a very important time of transition and learning for me. Photography became my therapy and a tool of expression that helped me survive and deal with personal issues, including the time when I was studying at Ryerson and my mother was unwell.

I can’t say that any singular thing or any singular person has been my influence. Experience is my driving force and my experiences have been my influences; these change, and how I understand these experiences also change. What I felt and where I was in 2016 is not the same as in 2018 and those shifts are reflected in the visual material – hence I speak about ‘phases’ in my series. In 2020, the context has changed for all of us and so have our experiences. We fear the unknown in a whole new way and for someone that works with images, this presents a new form of influence.

There has been a sea-change in the visibility of Black artists in the West, and artists from the African continent in particular, which has happened relatively recently. Why now, in your opinion? Has the art world woken up, or been shamed into opening up, or is there a generation of artists whose work demands to be seen? Or, is it all these things and other reasons besides?

The intergenerational conversations, traumatic experiences and collaborations within institutions and communities has led to the rise of visibility for Black artists in the West and across the African continent. It is clear that across the world people were questioning the institutions and ways of thinking that kept them on the sidelines, implying we were not worthy.

In South Africa, although apartheid ended in 1994, it was with movements like Rhodes Must Fall [a protest movement that emerged on 09 March 2015 at the University of Cape Town, in reaction to a statue of Cecil Rhodes, the ardent imperialist, and evolved into a wider movement to decolonise education across South Africa], and Fees Must Fall [a student-led protest movement in October 2015, which spread throughout the country and demanded an end to rising student fees and an increase in government funding of universities] almost 20 years later – that we started having long conversations about privilege and how cycles of oppression are maintained.

This discrimination starts within education: young Black kids were being told in school that their natural hair was unclean or messy because it did not grow straight or fall on their shoulders. It took 20 years for us to really acknowledge what this meant and call it by its name. In other parts of the world, Black Lives Matter has been growing; in the UK, the Grenfell Tower fire asked people to really think about who gets to count in their society and who doesn’t.

Race, class and privilege are intimately connected to wealth, access and exclusion. The world of art is not isolated from all of this – it is informed by the time it is in as well as the context in which it operates and continues to operate. It is also crucial to remember that Black artists have always been there, working tirelessly with these issues. But they were written out of a history and a world that wasn’t yet prepared to see them. Things are changing, but there is a lot of work to be done.

The last time your work was shown in London in the context of a major solo show, it was at Autograph, and it was one of the first showings of Somnyama Ngonyama. Returning for a solo exhibition at Tate Modern, a rarity for any kind of photographer, let alone someone of your age, does it reinforce the sense of how much Somnyama Ngonyama was a game-changer in how your work was received and perceived?

As per your previous question, there has been a sea-change in the visibility of Black artists recently. As a socio-politically engaged visual arts organisation that champions issues around visibility, race and representation, Autograph has been at the forefront of advocating for Black artists such as myself for decades — long before this present moment. Looking at it more broadly, it is important to pay attention to how this ‘sea-change’ is connected to the change in how we engage with imperial histories and Black bodies within those histories. Last year, museums were being held to task to return artefacts acquired through colonialism — you can see this as ‘the formerly othered’ saying ‘enough is enough’.

Somnyama Ngonyama does the same, it speaks to these issues clearly and openly, and I am glad to know that mainstream institutions like Tate understand this and have the willingness, presence and enthusiasm to engage. However, the exhibition at Tate is not only of Somnyama Ngonyama. It is a survey of my whole practice.

“The project addresses my own experiences in our society head-on: things that are painful, and I would not expect anyone else to carry that with me. I had to do it myself”

In recent years, your work has been exhibited in major solo exhibitions around the world. Why do you think your work has made such an impact, and how have you harnessed the exposure for your visual activism? What has been your experience of exhibiting outside South Africa, in institutions that may have historically rejected your work, or are tied to the history that you are trying to rewrite?

It is the lack of our own visual narratives and a willing audience that has led to my various exhibitions around the world. The world we’re in today is different from the world of 20 years ago — even the world of May 2020 is different from the world of January 2020. In my practice, decades of previous work is being acknowledged now, for the first time, because people are ready to think differently, even the institutions that might have excluded this work before are now seeing it in a different light.

I think we’ve arrived at this point because of the never-ending efforts of other activists and organisers in the community. My work specifically deals with making and rewriting a visual history of Black LGBTQIA+ people for archives and posterity. I am focused on matters of representation. My images are portraits, so if my work is being exhibited, someone else’s existence is also being affirmed. What matters is having a dialogue — with people, with institutions and with history. It’s a collective project of reclaiming space.

Is contemporary South Africa having a moment, culturally speaking? Will we look back at this time with admiration? It seems like there is so much coming out of South Africa right now – not just photography, but music and fashion – how has this impacted your work?

As said previously, sometimes it’s not that a place or a group of people are ‘having a moment’, it’s rather a matter of other parts of the world being willing to listen. There are a lot of talented and creative people in South Africa gaining the world’s attention, but there are as many being ignored. Lack of resources and lack of access are still big issues, and not everyone is privileged to access cultural or educational institutions. I’m glad that my work and my community are being received in this way, and I’m excited and honoured, to help pave the way for others.

One of your central aims is to establish a visual language for, and an archive of, the LGBTQIA+ community in South Africa. How has your approach to this evolved and what elements have remained constant? How would you describe this visual language?

The visual language has a lot to do with pride, dignity and self-respect for those featuring in the series. The still images and video works produced are based on a common understanding of what needs to be achieved so when we plan our shoots the best possible form of representation is key. The participants dress in ways that make them look good and they pose in ways that make them feel comfortable and proud of themselves.

I say that there are a lot of things to be angry and sad about, but when we are taking portraits we can be our best selves. Our lives are often in peril and that is what the media often fixates on, so my aim is to build an archive that reflects that our lives are not only about fear. The message is that we have agency, personality and personhood, and that has remained constant in my work.

You refer to yourself as a visual activist. Why is photography so powerful in the context of activism; what can it achieve that other mediums cannot? Conversely, your work deals with serious issues, but, is there also another side to it that doesn’t get asked about? Are you interested in the pleasure aspect for viewers of looking at and appreciating your photographs?

I consider myself a visual activist first and foremost because my work has a political agenda. What is important to me is how my work challenges and contributes to society and the place of Black LGBTQIA+ people within it. I picked up the camera because there were no images of us that spoke to me at the time when I needed them the most. I had to produce a positive visual narrative of my community and create a new dialogue with images.

With all of this, however, I’m still interested in the technical aspects of photography such as light and composition. I choose to work with silver gelatin printing because it amplifies what is pleasurable in the images. I’ve said that my work focuses on people’s dignity and using the camera to reflect their beauty is an extension of that. People have the right to be seen with grace.

Your work has been described as “mourning and celebrating”. How does it embody this duality? I can think of the series Only Half the Picture, for instance, which celebrates the love and intimacy of the LGBTQIA+ community, while also representing its trauma. Why is this duality significant? How do you reconcile the discordance between the beauty of your work and its darker underlying narratives?

Narratives around the LGBTQIA+ community have historically been negative. From being classified as a mental illness to being labelled un-African, the violent stigma around HIV/Aids and hate crimes including rape, the story is often only ‘half the picture’. So, with Only Half the Picture, I decided to show what is often left out of mainstream portrayals.

Lives have joy and sadness, including the lives of LGBTQIA+ people, so this duality is something we all have to face and live with. I try to reflect both of these because anything else would be a lie.

In Only Half the Picture your subjects are anonymous, while in Faces and Phases they hold the viewers’ gaze and are identifiable by the captions. In Somnyama Ngonyama you turn the camera on yourself. Why did you abandon the element of anonymity, and turn the camera from focusing on others to focusing on yourself? Why did the face become so central?

Each of my projects is about giving participants the most dignified representation possible. In Only Half the Picture, the series is more about intimacy, privacy and body politics within our community, rather than about specific individuals. Faces and Phases is specifically about affirmative portraits of lesbian, bisexual, trans and non-binary individuals – everyone is asserting their place in history and the world; and so naming, placing and timing are necessary.

Somnyama Ngonyama is a body of self-portraits that deal with politics of representation, race, and Blackness. I use my own body and face because the work is meant to be confrontational, both personal and political at the same time. The project addresses my own experiences in our society head-on: things that are painful, and I would not expect anyone else to carry that with me. I had to do it myself.

Anonymity is neither abandoned nor embraced in any of these works, and most importantly: the face is always central. Most confrontations begin with our faces. And to face the camera is to open a conversation – to make yourself both vulnerable and powerful at once.

Zanele Muholi’s survey show opened at Tate Modern, Bankside, on 05 November 2020 and ran until 07 March 2021. Zanele Muholi at Gropius Bau runs from 26 November 2021 to 13 March 2022. This article was originally featured in the July 2020 edition of British Journal of Photography magazine.

The post Zanele Muholi: Art and activism appeared first on 1854 Photography.